by Christina Waters | Nov 15, 2021 | Home, Movies |

Before I get down to serious ripping and shredding, I need to get this off my chest.

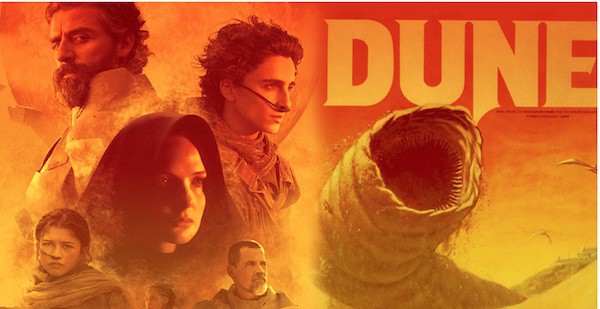

As a baby boomer, I read and thrilled to Frank Herbert‘s prescient, imaginative, and mythic futuristic novel. Canadian director Denis Villeneuve, of murky self-important Arrival fame, has taken it upon himself to launch an almost-three hour cinema version of Dune. This was an error of epic proportions. The badness of this film is the only thing close to epic in this exercise of cine-waste so awful, so clueless, so dis-inspired as to defy reason.

Villeneuve’s Dune is also murky, lethargic, impenetrable, and boring. What he has done to a seminal text should be illegal, like using the Holy Grail as a jello mold. All I could think, as I reeled out of the theater on a salt high, thanks to over-priced movie popcorn, was: how could I get back those three hours of my life?

Grab a sharp stick, aim it squarely at your left eye (or right, whatever you like) and stab! You will thus experience a more pleasurable sensation than that delivered by the clueless Canadian and his unpleasant cast.

Okay.

Now I can begin. I’ll start with the most egregious error made by this bloated production team: casting. It’s hard to recall casting this misguided, even hilarious, since that big blonde gentile Charlton Heston sauntered down the mountain with stone tablets in The Ten Commandments.

Starting with the worst: wasp-waisted Timothee Chalamet as the fierce, psychicically gifted messianic avatar Paul Atriedes. Chalamet would be fine in a bio-pic playing the young Oscar Wilde. Ideally in a film without any speaking parts. Chalamet was wretched as well as utterly unbelievable as the heir apparent to a powerful royal dynasty as well as leader of the new eco-desert utopia on Arakis. Yet, there might be five minutes of this almost 3-hour film in which the anorexic teen idol does not appear. He is so not up to the task that his mere presence inspires fantasies of the merely awful Kyle MacLachlen in David Lynch’s lackluster attempt to bring Dune to the screen 40 years earlier.

Maybe worse is the presence of Oscar Isaac. His mere presence on-screen is cause for genuine alarm, but to watch him attempt something like gravitas as Paul’s ill-fated father Duke Leto Atriedes is akin to enduring a three-hour root canal procedure. Does no one understand the importance of vocal power and nuance in filmmaking these days?

Rebecca Ferguson as Paul’s mother, the supernaturally trained Lady Jessica who teaches her son the special powers of her psychic order the Bene Gesserit, has an appropriately intelligent voice. We believe that she believes what she’s saying. Yet she, as all the others, is sabotaged again and again by a silly script.

And Josh Brolin as the adroit, amiable fight master Gurney Halleck? Not bloody likely. Brolin, with his Marine haircut and fatigues, looks like he stepped out of another film, and another timeline. He should have checked in with his acting coach before filming. So should Sharon Duncan-Brewster, who looks great as the double agent Shadout Mapes, but again, appears to have no working knowledge of the script, its language (English), or its meaning.

Another who needs slapping around is the once great Javier Bardem, a wooden cartoon of the mighty warrior of the desert tribe, the Fremen. All I could think of was Anthony Quinn as the Bedouin leader in Lawrence of Arabia. Quinn was more believable.

Here I’ll circle back on poor matinee-idol-du-jour Chalamet, who is burning through his fifteen minutes like an addict through fentanyl. So physically wraith-like and awkward as to mock the idea that he could match knives with the Fremen soldier who calls him out, Chalamet appears not to understand or care what he is doing. Indeed, he appears embarrassed to be in front of the camera, especially given the lingering closeups he has to endure. Is he Villeneuve’s fantasy boy?

I’m too exhausted to continue.

My next installment of Dune demolition will involve asking whether ponderous camerawork, massive explosions and a behemoth score can actually substitute for a script, dramatic tension, excitement, inspiration, and/or (god help us) acting.

to be continued…..

Desert Bomb: Part II

by Christina Waters | Nov 14, 2021 | Movies |

Just thinking about continuing my assessment of Denis Villeneuve’s bloated bomb makes me reach for the gin. You’ll recall I decided to address whether ponderous camerawork, massive explosions and a behemoth score can actually substitute for a script, dramatic tension, excitement, inspiration, and/or (god help us) acting.

Courage!

Rarely has so much money been thrown at such an empty concept for remaking an earlier semi-bomb. At least the original 1984 Dune had a certified genius—David Lynch—sinking the ship.

Uniforms like these aluminum foil origami jumpsuits, [see above shot of special-needs actor Josh Brolin posing next to self-important actor Oscar Isaac] made me nostalgic for the spectacle of Kyle MacLachlan fighting uber-hunk Sting in the original cinematic Dune.

But onward! Visuals: Shall we begin by asking how many Architectural Digest decorators it took to polish the concrete fortress walls of the House of Atreides? Tunnels of grey, leading to rooms of grey, occasionally occupied by individuals in grey. I’ve seen bus station waiting rooms with more style than the royal chambers of our central figures. The camera obsesses over the acreage of grey that forms the central heart of this lumbering film.

Maybe the interiors were designed by fashion people, you know, Prada, or Chanel, or Alexander McQueen so that when the female actors glide from one grey hall to another, we could admire the way their diaphanous robes billow in the wind machine airflow. Yes. That must have been the thinking behind the cavernous, dark interiors. Catwalks of the future. [Note the post-Taliban exoskeletons in which our principals are dressed for desert life.]

And how about the decision to have big guy Jason Momoa, playing the wiley Duncan Idaho, do his acting entirely with his eyebrows! Ugh.

How about long, self-indulgent camera shots? The Valium-scented overhead shots, the countless drone shots, the shots designed to substitute for the missing: A) script, B) insight, C), narrative arc, or D) dramatic tension. No worries. Just keep the camera rolling, tack on an extra half hour, and gamble that the Cannes crowd will eat it up.

Another secret of Villeneuve’s concept: no editing. Just take after take after take. Again for reasons noted above: keep viewers off-balance so they won’t notice the vacuity of the cinematic text.

And throw in many explosions. Explosions requiring loud booms. Here the visual barrage meets the sonic barrage.

Score: And that brings me to the once-notable Hans Zimmer, composer for Gladiator, The Lion King, Inception, and a few others. In this film, Zimmer’s mega-decible score does most of the heavy lifting, drama-wise. During the final, interminable, 45 minutes of Dune (the one with teen throb Timothee Chalamet ((don’t get me started on the pretentious spelling of his name!))), Zimmer’s score IS the film. This device of making the sound do the work is cheap and obvious. Villeneuve ran out of ideas very early on, even though Frank Herbert (the book’s author) provided plenty of them. So he just cranked up Zimmer’s score, threw in explosions and Bob’s your uncle.

Loud. Very loud. And when the film still fails to revive movie-goers who have by now fallen into comas unalleviated by either popcorn or diet Cokes, Zimmer & company simply make everything louder.

And slow. Slow sand. Slow explosions. Slow loud music.

Let’s review: Dune is a book of eco prophecy, laced with compelling mythology, labyrinthean power conflicts, inventive sorcery and mysticism set in the heart of a desert scented by spice. And not just any spice. Spice that allows the consumer to intuit thoughts, feelings, and events both intimate and far into the future. At the center of this story is a young man who, thanks to his mother’s power and clairvoyance has been bred to exist in many temporal states at once. Yes my friends, long before Keanu Reeves, Paul Atriedes was The One. And no my friends, Timothée (pretentious spelling) Chalamet, is NOT The One.

Spend a more pleasant two and a half hours filling out tax forms, or calling AT&T Customer Service and waiting on hold to a continuous loop of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons.

Caveat Emptor! and if there is a god, Villeneuve will find himself without the funding to continue his cruel dismantling of Dune.

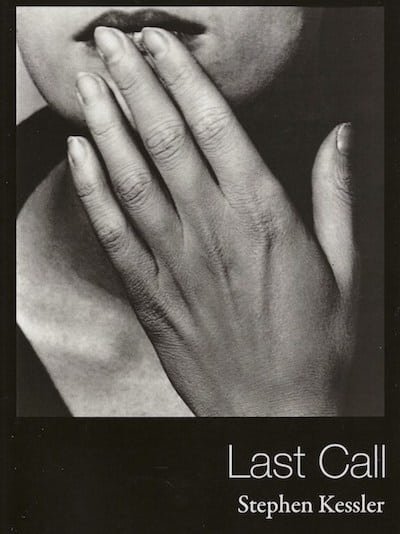

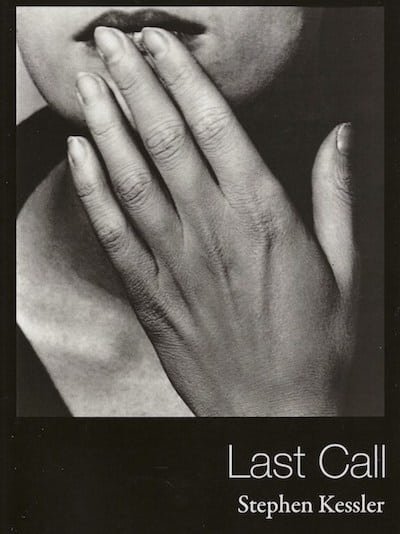

Last Call: Poems by Stephen Kessler

by Christina Waters | Nov 13, 2021 | Book |

Last Call: Poems by Stephen Kessler

Essayist, translator, pundit, and poet Stephen Kessler has been courting the muses for over 50 years. In his latest, largest, and 12th collection of poems, Last Call, Kessler’s elegant technique explores Santa Cruz, music, lost love, aging, irony, and pandemic epiphanies.

Q: Briefly tell me about how this collection of poems came about. What time period did they span? Where do they fit in your oeuvre?

My books tend to coincide with periods or “chapters” in my life. The poems in Last Call were written between January 2017, when I turned 70, and February of this year, when I received my first Covid vaccination. Those years happened to coincide with two terrible events in the personal and the public realm: the breakup of my marriage and the presidency of Donald Trump. So there was a lot of tough material to process, which accounts for the sense of grief and loss, especially in the first section of the book. “Bad Luck Charms.” My hope was and is through the alchemy of the language to turn all that hurt into something else—including ironic distance—the same way singing the blues can transform pain and heartbreak into something beautiful and consoling, maybe even funny.

Q: You’re known for the jazz syncopation of your poems, the way the lines stride and swing into each other. Do you read the work aloud as you write? or only afterward? How does it work?

I write by hand on paper (or with occasional exceptions on a manual typewriter) and try to let my hand do the thinking guided by the technical skills I’ve developed over about 65 years of practice, just as a jazz musician typically improvises spontaneously without reflection, letting the trained ear and fingers direct where the melody is going. I hear it in my head as it’s being written and try to just let it rip according to where the sounds of the language lead. Then I may read it to myself in a whisper to feel how it tastes as much as to hear how it sounds. If it feels more or less like natural speech but spring-loaded for torque from one line to the next, that’s the effect I’m hoping for. Sometimes it comes out right the first time and at other times it requires revision. But I always let it sit for a while to let it cool off so I can have a more objective look—and listen—at what I’ve written. If it’s not working, and I can’t fix it with a few adjustments, I tend to set it aside and move on to the next one, rather than try to save every poem by revising as extensively as I did when I was younger.

Q: I see more willingness to indulge in alliterative lines, in internal rhymes within the lines themselves. Were you consciously expanding your style in this collection?

Alliteration, internal rhyme, vowel rhyme and other prosodic devices have always served as my tools and techniques of composition, so I don’t see how this book is any different in that respect from most of my earlier work. But one’s style evolves, and I enjoy surprising myself from one line, one poem, and certainly one book to the next. At this stage of the game, I’m less concerned with writing a perfect poem (or a perfect book) than in letting the lines move to their own measure, so in that respect they may feel more indulgent or expansive in some way. But as I said, I’ve been reading and writing verse for so long—since childhood—that I feel enough confidence in my technical chops to let the poem take its own organic form. So there are lots of different shapes and sizes and styles of poems in this collection.

Q: Which muse pulled stronger, growing older or enduring quarantine?

Normally I’m accustomed to spending a lot of time at home alone with the writing, so the lockdowns weren’t all that inconvenient for me. But being increasingly old is something I don’t know if anyone ever gets used to, so the physical and psychic realities of entering “old age” (even though 70 is the new 50, and I’m reasonably healthy) play a much bigger part in the composition of this book—only the last year of which, maybe a dozen or 15 poems, was written during the pandemic.

Q: Can you reflect on the bittersweet irony of publishing your most ambitious late-career book, and calling it Last Call just when COVID shut down the world? As if the title were the leitmotif of the era itself.

The title came to me very early on, with the poem of that title, which I think was written about four years ago, so the pandemic had nothing to do with it. That poem was literally written at the bar of a local restaurant where the bartender was calling for any last orders before closing. It matched my gloomy mood of the moment and seemed fitting for the late-life themes I was wrestling with. Everyone asks if it’s meant as a valediction, and I think probably not, but then again, you never know. I certainly intend to keep writing, but that’s not entirely up to me. I expect the world will go on, with or without me.

Q: Much as complex recipes in fine cuisine, this work more than ever lays down opposing riffs—sweet and salty, joy and pain, darkness and clarity. A poet’s-eye view of the rhythm of existence itself?

In writing, as in cooking, I use whatever ingredients and seasonings are at hand. I definitely prefer a book—my own or anyone else’s—that moves through a range of themes and moods and motifs rather than repeats a formula over and over. Doesn’t everyone go through different rhythms of existence? Looking back over some 50 years of publishing, I feel as if I’ve consistently tried to respond as honestly as possible to the full range of my lived experience. I just hope I’ve gone deep enough that the poems resonate with the experience of others.

Q: You never draw attention to craft—form, composition, conscious/slant rhyming—in your work. Yet I have to admire the impeccable line breaks like some of these in “Last Call”:

trees crashing through

roofs, blackouts,

rivers rising and

spilling into living

rooms leaving a film

Does the spontaneous observation trump craft in your work? Or were these poems different in feel/form?

What you call “craft” I call technique, and it’s baked into the writing in a way that’s inseparable from imagination or observation, just as form and content in the best poems are seamlessly integrated. I learned the fundamentals when I was in elementary school by reading (for fun!) traditional English poetry (my family had a paperback copy of Palgrave’s Golden Treasury of Songs and Lyrical Poems) and writing imitations of rhymed and metered verse—usually just to entertain my friends. I wrote the lyrics to the class song for both grade school and high school graduations. I learned to write a poem for any occasion. Most of those efforts, when they weren’t intentionally funny, were no good as poetry except in a formal sense: they scanned metrically according to whatever form I was imitating, and they rhymed at the ends of the lines. So listening for rhythm and rhyme became habitual, and by the time, around 18 or 19, I started writing “free verse”—a misnomer because it demands even more formal control than fixed forms, requires that you create your own form on the blank page—these prosodic principles were ingrained in me. It took me many more years, decades even, to learn to deploy them effectively in composition, but by now I’ve been doing it for so long that the form the poem takes is second nature, and almost unconscious until I look and see what I’ve done. In the case of the title poem you quote from, the length of the lines was determined by the width of the notebook page I was writing on; the breaks just happened to work as written, so I didn’t mess with it. Other poems written in the same pocket notebook came out completely differently because I heard the breaks to fall in different places.

Q: Some poems in this collection are only a few words wide, forcing me to read downward (vertically) in a single gulp. Others stretch more words across the page, slowing down your voice and the reader’s intake. How do these decisions come to you?Funny, for me, short lines tend to slow a poem down, and long lines move more swiftly across the page. That just shows how we all read differently. As noted above, in some cases it’s the width of the page I’m writing on, or in the case of “Borges’s Belt,” it was the strip of paper I was typing on as the poem describes its own physical creation. “Paisley Yours” is in the voice of the model in the middle of a magazine page, and the narrow white space on either side of the image determined the long skinny shape of the poem as I typed it on my 1974 Adler manual portable. Others may start as prose in the first draft and once I see the whole thing I find where the breaks belong. And still others are composed originally as verse because the lines come to me one at a time and that’s the way I set them down. Most of these decisions make themselves according to how the composition unfolds. I don’t have any rational method, it’s a much more intuitive process based on the measure I hear in my head. I find the formal openness yet technical precision required of “free verse” to be as mysterious and unpredictable as how the poem’s images are imagined—usually by sonic association more than conscious choice. At best I feel like a medium, or an amanuensis to the muses, just taking dictation.

Q:Do you know when the words are good?

Usually—but not how. Sometimes in real time as they’re set down; at other times only later, from a more detached perspective. In some ways it’s easier to know when they’re not so good, when they’re clunky or prosaic or just “off” in some way. When the good ones are coming I’m too caught in the flow to really understand what’s happening, and when I see what I’ve done I can’t figure out how it happened. Composition as possession. I’ve learned to surrender to whatever it is that’s got hold of me, usually some kind of rhythmic riff, a few words strung together, a phrase unfolding according to its own melodic logic. And it feels good when the words are good—so I guess that’s how I know.

Q: Finally, an appreciation. “Discourse on Distraction” is a disarming piece of rumination, in which you move from the almost Platonic general down to the tangible specific. The last lines are among your finest, in which you clearly speak to the man within the poet:

there is no escaping the script you write with every step,

the strange rhymes ringing amid the dissonance,

the gifts, the great griefs,

the peripheral visions.

___________________________

Last Call, poems by Stephen Kessler

Black Widow Press, 200 pages, $19.95

Interview by Christina Waters

Zoom Forward reading Friday November 19, 5pm (Pacific time)