From its first slowly undulating chords to the last sweeping thunder of destruction, Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelungen carries the listener along on an enveloping artistic journey like no other. The opera anticipated cinema and more than captured the composer’s declaration that the four-opera odyssey is indeed “a total work of art”—Gesamtkunstwerk.

It’s a tribute to the magic of Wagner’s vision that in my sixth journey through the 17+ hours of the Ring, I still felt the electrifying effect of the operas as if for the first time. Being swept away by the towering orchestration, the almost impossibly modern conceptualization and sound—so many passages argue for their dates being a hundred years into the future of their actual mid-19th century debut.

This is a work of art that never fails to fulfill expectations. And more. Last month I was treated to the view of the sunset over the Danube four evenings in a row. My experience two weeks ago with the four operas of the hero’s journey and the gods’ downfall unlocked even more secret passages of the great origin saga, not only of northern mythology but of the deep tissue of human psychology, the foibles, vanity, greed, desire, trickery, and love.

The music itself is the storyteller. The stalwart singers often seem to be there simply to punctuate the underlying text which, like the Rhine itself, roils and deepens as it winds through the many strands of fire and water, earth and heaven that ignite the uncanny masterpiece.

Tomasz Konieczny as Wotan: photo Nagy Attila/Müpa

Tomasz Konieczny as Wotan: photo Nagy Attila/Müpa

The story, a sweeping melange of Teutonic myth, Norse fairytale, and dreamscapes from the archaeology of human psychology, tells of the obsession of trolls, men, and gods for a ring of gold, a ring that brings limitless power to its owner. Changing hands over and over—and never by legitimate means—the ring has been forged by gold stolen from the Rhinemaidens, and the course of the operas takes us to the creation of Valhalla, home of Wotan the ruler and his family of gods.

The saga awaits a pure and fearless hero, Siegfried, who can win the power of the ring by slaying a dragon (it’s complicated). He wins the ring as well as the love of Wotan’s Valkure daughter Brunnhilde until greed overcomes his foes, and the gods, Valhalla, and our heroic lovers all go up in flames. And yes, the gold finally returns to the Rhine in the end, with music repeating the opera’s opening musical themes coming full circle in an ending that is both unspeakably tragic and emotionally satisfying.

The four operas unfold over more than 17 hours and in the best possible world there are singers on the stage capable of sustaining a spell throughout those hours. It is a tall order that few can deliver. The charismatic cast for last week’s Ring cycle at the Bela Bartok concert hall in Budapest frequently held the audience in thrall. Stamina, superhuman breath control, and in the case of the soprano singing Brunnhilde, many high Cs even after long stretches of non-stop singing. Many aspire to these roles in the absolute pinnacle of opera.

Nagy Attila/Müpa

Nagy Attila/Müpa

I went to Budapest for two reasons: Wagner, and Wotan as performed by the great Polish bass-baritone Tomasz Konieczny [here with Christian Franz as firegod Loge]. The part of the mercurial king of the gods is arguably the most interesting in a cast of brilliant and volatile characters, including scheming underworld denizens, comedic forest dwellers, jealous goddesses, giants, a dragon, starstruck lovers, and tribal warriors. Wotan—would-be Lord of the Ring—is consumed by the all-too-human desires for endless power and infinite romance. I heard Konieczny sing Wotan in Vienna a few years back and like others in that audience fell instantly under the spell of his brooding and finely calibrated interpretation. Konieczny is a fine actor, a splendid singer, and attractive enough to make you realize just why even the earth goddess herself would fall for him. Possibly the finest Wotan in opera today, Konieczny—in the formal attire—rivals Daniel Craig for tuxedo cred.

Dinner each evening during the second one-hour intermission.

Dinner each evening during the second one-hour intermission.

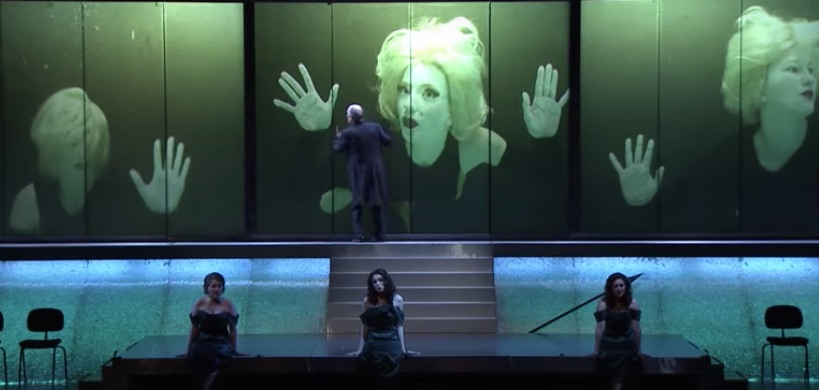

The semi-staged concept seen in the Müpa Wagner Days productions gave me a new perspective on the Ring. The architecturally brilliant hall is not an opera house. It is a concert hall. That means no proscenium stage, no wings, and no curtain. It is a stage that has been given a few bits of architecture, notably a central stairway leading up to a wide screen on which are projected various atmospheric videos, and around which characters can come and go to suggest changes of scene. The singers all were clad in black formal attire—tuxes for the men, gowns of varying descriptions for women. The orchestra pit was just in front and below the stage, about 20 feet from my raised side seat, a version of a box seat.

The effect of this minimalism was that the opera was immediate and intimate. No sets or built scenery got between the music and the audience. The singers became actual characters in the story, a Singspiel almost in bardic tradition, as much as acted out. In other words, there was nothing to get in the way of the glorious music (except for a troupe of dancers, whose movements echoed the sung story, to mostly distracting effect).

It was my sixth Ring, and with each viewing the story grows clearer and deepens. Wagner is very carefully and lovingly reconstructing the Creation myth of German identity. The story is everything, and it is given the greatest possible music as its vehicle.

Konieczny, a true Helden-baritone is a superb actor, delivering the emotional complexity of Wagner’s vision with expressive body language and vocal nuance. The powerful voice is capable of standing up to the composer’s dense instrumentation. And he can do it for many hours across the operas. As the frustrated god ensnared by his own traps, Konieczny illuminated the eternal truth of Wotan’s passions and regrets. He appears to consider, to negotiate, to weigh the dimensions of everything he’s saying and doing. And yet the singer has performed this role dozens and dozens of times. All the irony and folly, that the gods are only as great as their worshippers, and always as small as their own addictions. comes out clearly. Master as slave.

Konieczny, a true Helden-baritone is a superb actor, delivering the emotional complexity of Wagner’s vision with expressive body language and vocal nuance. The powerful voice is capable of standing up to the composer’s dense instrumentation. And he can do it for many hours across the operas. As the frustrated god ensnared by his own traps, Konieczny illuminated the eternal truth of Wotan’s passions and regrets. He appears to consider, to negotiate, to weigh the dimensions of everything he’s saying and doing. And yet the singer has performed this role dozens and dozens of times. All the irony and folly, that the gods are only as great as their worshippers, and always as small as their own addictions. comes out clearly. Master as slave.

The emotional pivot of the operas happens near the end of the second, and possibly best known of the four operas, Walküre. Angry at her disobedience, Wotan is forced to punish his beloved daughter Brunnhilde, the one who understands and knows him best, by casting her out of Valhalla. Utterly convincing in the heartbreak of a father forced to banish his best-loved daughter, Konieczny delivered indelible tenderness. Here is the beginning of the twilight of the gods, as Wotan’s fierce warrior daughter is suddenly plunged into mere womanhood, made mortal.

As the Brunnhilde for that single night, British soprano Allison Oakes stepped into a genuine star-is-born moment when the original singer, Irene Theorin, was forced to cancel due to illness. Believably vulnerable, defiant, and best of all in great voice she won over fellow singers and the audience as well. Konieczny graciously supported her performance, deferring to her in stage position and in emotional intensity. Tears filled my eyes during their final farewell embrace. It was a brilliant pairing of voices and intuitions and when they came out for a bow at the end of the opera, Konieczny and Oakes hugged each other and bounced up and down with sheer joy at the performance they’d just given.

Many wonderful singer/actors in definitive roles throughout the four operas. A splendid Fricka, much-cuckholded wife of Wotan, sung by Atala Schöck, Nadine Weissmann (singing via video-tech) as the earth goddess Erda, and a persuasive Sieglinde, sung by Karine Babajanyan.

The scheming troll Alberich was performed with delicious bravura by Jochen Schmeckenbecher, the substantial part of comedic villain Mime was sung by Cornel Frey, and the charming giants, by basso-profundos Fafner (Walter Fink) and Fasolt (Sorin Coliban) who were shadowed by enormous puppet surrogates who loomed over the stage while Wotan quibbled over giving the coveted ring in exchange for the captured goddess Freia (Lilla Horti).

But there were production issues, notably the very slick and steep staircase in the centerstage. It allowed performers to change vantage points for dramatic purposes, but it also caused frequent slipping, sliding, and in one case an actual tumble. The atmospheric video displays on the screen at the back of the stage were effective in creating a sense of changing mood and setting. A small company of extraordinarily limber and graceful dancers often arrived without any particular motivation, cluttering the stage just at climactic musical moments, frequently breaking the spell. Such a device, adding pop-up texture on an otherwise bare stage, is an innovative and often successful solution. As when the dancers writhe on the stage below the singers, acting as the trolls working in the goldmines deep below the earth. And there were two dancers dressed in red suits, who appeared frequently to help guide the gods up or down the Valhalla landscape, again, annoyingly.

Another issue: The seemingly tireless tenor Stefan Vinke gave his energetic all to the enormous role of Siegfried, the hero who knows no fear, yet incessant grinning and fist-bump gestures managed to take his character out of the innocent hero category straight into clueless good ole boy territory. He did manage the arduous love duet with Brunnhilde with all the high notes intact, less so during the long last opera. When forging the sword Nothung in the third opera, his resounding “ho ho ” passages were confident and compelling. Truly a helden-tenor delivery of the booming top notes.

Hirling Bálint/Mupa

Hirling Bálint/Mupa

And another: As the Brunnhilde of the final two operas, Catherine Foster was a visual curiosity, tugging on her too-tight spandex costume and holding her arms in the awkward chicken-about-to-strike pose. Eyes always on the conductor, her voice was often glorious, but more often she failed to arrive at the top notes in crucial passages. Even less convincing was Petra Lang, who I’d seen in Bayreuth as a seductive Ortrud in Lohengrin, and as a passable Brunnhilde in Vienna. Singing the Valkure Waltraute, arriving to persuade Brunnhilde to return the ring to the Rhinemaidens and end the downward spiral of emotions and violence, Lang preened and pouted as if giving a command recital. No tender pleading, all vibrato-tainted grandstanding.

As always with the Ring, it is the orchestra—passionately led by conductor Adam Fischer—who carried the evening. The enormous horn section, the tireless precision of the strings, the celestial shimmer of six extra harps positioned three on each side of the top balconies, the Hungarian Radio Symphony Orchestra was moved firmly through the four days of music by maestro Fischer. The conductor has said that the Ring “is the kind of intense journey that cannot be interrupted.” And it wasn’t. At other venues, these four operas take place over a longer stretch of time, with a day or two break in between the long hours of performance. Here at the Müpa production it was possible to stay completely engaged each day, without a break, until Valhalla’s flames are finally quenched in the waters of the river. Surely this is one reason why several of the large roles were performed by two different singers. Two Wotans, two Brunnhildes. It was arduous and yet unforgettable to stay within the magic of the unfolding story, night after night, until the stunning end.

One musicological note. At the end of the first opera, Das Rheingold, as Wotan leads his family of handsome gods and goddesses up to their shining new Valhalla, Wagner has scored a luscious bolero. The blatantly sensuous rhythm of this procession to the home of the gods implies success, security and triumph. Such bravura makes it all the more poignant when bit by bit the immortality, composure, and fortune of the gods crumbles. It is a huge fall, underscoring the hubris of trying to have it all, and the corruption that comes with the quest for power.

seems like no matter how it’s staged Wagner still triumphs…a never ending plot…full of mystery, drama, and never answered questions!!!

Thanks for your insight!!

Gorgeous writing, Christina. Really enjoyed reading it and meeting you too, as brief as it was! All best to you from Budapest!

Wow! To a Wagner novice of the “kill dee rabbit” school of exposure, you made this Ring Cycle indelibly clear. Thanks for a great and illuminating review that shows why this art is so much more than I thought!

I hope your writing will be published! so vivid and alive and accessible