Parsifal: Twilight of a Production

Having traveled 5000 miles to dive into the Opera Bastille production of Wagner’s final opera, I was poised for a memorable experience. And while I certainly got one, it was mostly for the wrong reasons.

Here’s the short version.

Conducted by Wagner veteran, Simone Young, the Paris Opera gave a fine reading of music so romantically breathtaking that it defines “sublime.” Excellent throughout, the orchestra managed to hold out against a mesmerizing yet ultimately destructive production, perpetrated by director Richard Jones. The elaborate set, moving on invisible tracks to reveal ever more chambers and levels, was clever, ludicrous, puzzling, and silly.

The costumes were blatantly ugly, and while we don’t always expect singers who are svelte, or who are also good actors, we could hope for more than the baggy shorts, backpacks, and sweatshirts most of the principals had to endure. Also terrible—save for the stalwart Kwangchul Youn as Gurnemanz, and Falk Struckmann as Klingsor—the singers had their eyes glued on the conductor for most of the performance.

photo: Vincent PONTET

The chorus was wonderful. And even though the music simply cannot be ruined, the production design tried its hardest to cut deeply into Wagner’s spiritual vision. Trashing the concept of Parsifal’s innocence overcoming magician Klingsor’s malevolent genetic engineering, the Act 2 Set of lusty flowermaidens jiggling fake boobs and buns non-stop, was tiresome. This four-year-old production felt distinctly dated.

Nothing this production threw at the audience did anything to illuminate new vistas, or unprobed corners of this complex work of art. The final act was inexcusably boring. Three people, standing around on a nearly bare stage, singing at each other (and none too well) for over an hour.

Now for the longer version.

Conductor Simone Young moved the Paris Opera orchestra smoothly through the depths of Wagner’s final opera, the entire ensemble firmly in her eloquent hands.

The underlying spirituality of the composer’s great music-drama “consecration” came through clearly, despite the visual antagonism of an agnostic setting and shallow visual interpretation.The point is made clearly by the great horn motifs and ascending chromatics of chord structure, the rising colors of the sound as if sunlight suddenly thrusts through the rose window of a great cathedral. Music and setting contradicting each other whenever possible.

As the opera moves us through an often incomprehensible maze of myths, metaphors, and magic, the composer summarizes his own repertoire, unafraid to quote his own work, to borrow from his own splendid musical themes.

While contemporary, even futuristic visual settings are often effective in reinforcing the romantic timelessness of the story, in the case of Richard Jones’ concept quite the opposite is true. The clever but overwrought transplantation of the story into future of cultish monasticism fail to move our understanding any further. The flower maidens as GMO-creations of exhaustingly explicit sexuality—less would have been more. The elision of sports cults and religious fanaticism, while perhaps persuasive, again didn’t illuminate the overall genius of this last work of the great master.

For that, we had the music itself.

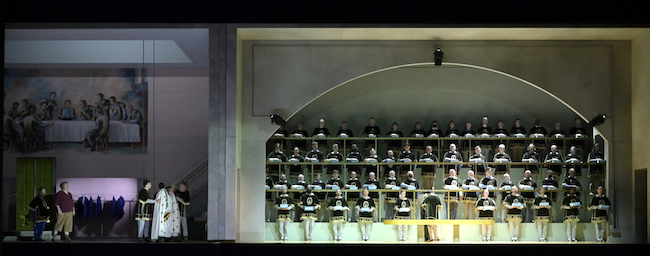

Here’s the best place to focus on the complex set, which moved laterally to reveal ever more chambers, and in some scenes multiple levels. An arresting illustration of the opera’s mythic words: “here Time becomes Space.” From the study hall of what appears to be a cult devoted to “the Word,” the set moved the actors into austere chambers containing the bleeding Gail lord Amfortas and in a small bedroom upstairs, the dying founder of the Grail knights, Tintural. As the set continued to expand, it revealed a conference room crowned by a mural of a proto-Last Supper, and finally into a huge sports arena lined with row after row of cult followers (the mighty Paris Opera choir, flawlessly trained by choral director Ching-Lien Wu).

Calling lots of attention to itself, the set was alternately effective and silly, inspired and stupid. This production by Richard Jones feels smug about itself, the clever set as visual tour de force, with robotic cult members whose movements have been honed to within a goose step. And yet without the rapture implied by the chromatically mutating music, the entire production comes off as ironic and sterile.

The complete opposite of the semi-staged Ring I went on to see in Budapest, where minimal staging allowed the music and voices to cast their spells with emotional intimacy, the Paris Parsifal felt robotic, overwhelmed, and tired. Hopefully it will be retired for something fresh. Perhaps something that has more to do with the music, and less with the sort of fashionable revisioning that can completely undercut the musical ideas. The Frank Castorf Ring in 2013 comes to mind. Or the Sebastian Baumgarten Tannhäuser in which grotesque romping monsters obliterated some of the most gorgeous music ever composed.

Photo : Vincent PONTET

In warmup suits as if about to attend a sports contest—the Paris Open perhaps?—the old faithful knight of the Grail, Gurnemanz, was given stalwart voice by Parsifal veteran Kwangchul Youn. I’d heard him in the 2014 Bayreuth production in the same role, and his resounding and tireless musicality seemed not to have aged. As the wounded Grail lord Amfortas, Iain Paterson looked and sounded exhausted. As the pure fool, Parsifal, Simon O’Neill relied on almost non-stop eye contact with conductor Young as if uncertain what his next lines should be. The mercurial time-traveling witch Kundry, dressed in hipster backpack and sweatshirt sung by Russian mezzo-soprano Marina Prudenskaya, was neither believable nor vocally engaging. By the end of the opera, she had devolved from temptress to penitent, and then finally as best buddy to the hero with whom she sauntered off-stage hand-in-hand. In Wagner’s original version, Parsifal absolves her wickedness and she gratefully swoons and dies.

The last act, incomprehensibly sung against a bare stage, is inexcusably boring. Why have the newly repentant witch Kundry, and the newly awakened Parsifal, explain their realizations in a completely empty space? Vocal precision and color might have helped. But these were alas also missing.

Would that this bewildering yet majestic music had been sung by brilliant voices. As it was, the June 6 performance left me longing to have heard the 2018 debut version of this production, with the acting genius Peter Mattei as Amfortas, heldentenor Andreas Shager as Parsifal, and the rich and adroit mezzo of Anja Kampe as Kundry. The veteran Wagnerian Falk Struckmann, as the malevolent magician Klingsor, announced through a spokesman at the start of the opera that he was not in his best form that night. My heart almost stopped. I’d been a fan since I saw him as Hagen in the Vienna Ring five years ago. A savvy actor, Struckmann performed nonetheless and even in less than perfect form he sounded better than most of the others on that stage.

The costume designer owes an apology to singers and audience Baggy clothing on Parsifal, fussy and dowdy costumes on Kundry, woefully malfunctioning fake blood on the robes of Amfortas, and the hilarious X-rated gyrations of the genetically engineered maize maidens made this Parsifal a pleasure only if you closed your eyes.

The ascending fifths of the Dresden Amen still worked their redemptive magic, and while this production makes almost nothing of the spiritual thrust of this opera, the splendid orchestra rose to the occasion. It made sense of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s confession that while he loathed the Christian theme underlying Parsifal, he had to admit the music was sublime. Sublime and worth the five hours and 5000 miles I’d traveled to enjoy.

Orchestre de l’Opéra national de Paris