A Ring for Generation Z

by Christina Waters

As the final Cycle of Bayreuth’s 2023 Ring came to a close, the air remained electric with the sounds of Wagner’s apocalyptic horns and the rapture of the Rhine. [see my Operawire review of the Bayreuth Parsifal here.]Camps came away divided into those either outraged or captivated by director Valentin Schwarz’ reinvention of the gods’ messy journey to oblivion. To be fair, there was much to decry for purists who come to worship at the shrine built by Wagner. In settings that cross-referenced reality TV with darker strains of Freudian family feuds, Schwarz’ imagining of the Ring as a downward spiral of superficial desires and twisted repercussions is bold. And in my opinion both brilliant and prescient. That said, much remains to be fully resolved, tweaked, and workshopped in both the opening das Rheingold and especially Götterdämmerung, the finally opera of the tetralogy. These two opening and closing dramas of Wagner’s epic internecine struggle were so stained with visual non-sequiturs as to practically obliterate the splendor of the score.

[all photos: credit Enrico Nawrath]

[all photos: credit Enrico Nawrath]

The ongoing dissonances that wove throughout Schwarz’ conceptualization of the Ring were both its power and its disenchantment. A prime example was in the shimmering declaration of love and ardor, Winterstürme, Siegfried’s matchless love song to his sister/bride Sieglinde. Perfectly partnered by emerging star Elisabeth Teige as Sieglinde, the golden-toned Klaus Florian Vogt gave full actualization to the role of Siegmund. Yet as the music and Vogt’s voice were soaring through some of the most beautiful love music ever written, the concept was busy tinkering with Elisabeth’s pregnancy, which shows up even before Sigmund does. Splayed awkwardly across a staircase, Teige endured possible sexual probing (or was it the desire to abort the future hero, Siegfried, she is carrying?) by Wotan, even as Vogt lifts his voice toward a perfect world in which the twin lovers will live happily ever after.

The majestic music, lifting and purring securely under the firm control of maestro Pietari Inkenin, never faltered. No matter what the stage narrative told us, Inkenin was armed with understanding of the text and a heroic orchestra, filling the matchless acoustics of the Festhalle. But the visuals had the audience squirming. And this is the key to Schwarz’ vision, for better and worse. Unlike many of the high fashion Wagner productions, such as Herheim’s Parsifal, or Castorf’s Ring, Schwarz doesn’t seem to be simply updating imagery and characterizations in order to shock, provoke, or show off for its own sake. He has an obvious, and—at its best—illuminating vision of a world devolving thanks to the moral bankruptcy of the older generation. In lecture remarks the 34-year-old Schwarz maintained that he wanted not simply to update the Ring, but to make it accessible to today’s audiences. In stage directions cast he asked his cast to sing what the 19th century composer wrote, but to act with their own 21st century gestures and attitudes. As a result this Ring is a literal refreshing of Wagner’s grand motifs. Schwarz gives us a dysfunctional family drama within the post-capitalist rubble of a disintegrating natural world. The real world as we know it!

[Wotan making a guest appearance at Mime’s forge]

[Wotan making a guest appearance at Mime’s forge]

All of which means there is no ring, no Tarnhelm, no gold-hoarding Nibelungen, no horseback Valkyries ho-yo-to-hoing down from the skies. Instead of the Rhine river, there’s a shallow swimming pool. Mesmerizing yet utterly bizarre, the formidable Valkyries are now Beverly Hills housewives recovering from plastic surgeries, all costumed ala Barbie. Schwarz has a sense of humor as well as a concept! Over-the-top Instagram groupies costumed in pink, orange, and red, Wotan’s statuesque offspring laughed, preened and compared breast enhancements, a giggling hell for their profligate father to regret. This Ring is a tale of bad faith with benefits. And there’s not a boring moment in it.

Subliminal Leitmotifs

Wagner’s famous leitmotifs have been shaken up to serve a contemporary reality, and how those motifs shape individual character’s desires also shape-shifts along the way. Instead of a magic helmet, Freia’s shawl is the house fetish carried forward by various characters as a security blanket throughout the four operas. The same for a persistent rocking horse which, as a small toy, as a trinket, as furniture, as Grane, occupies the mis-en-scene throughout. What Schwarz’ recurring symbols mean is not in any way tangible, or defined. But how they have meaning is as clear as the subconscious itself. Moving throughout the four operas is an illuminated pyramid, lit from within, which the various characters hold, or bring with them into the arenas of family feuding. Clearly a cherished object, the pyramid holds our interest and curiosity. No small accomplishment throughout 17 hours of opera!

[Icelandic baritone Olafur Sigurdarson as scheming Nibelung Alberich]

[Icelandic baritone Olafur Sigurdarson as scheming Nibelung Alberich]

Some of this tinkering with our expectations takes a while to gain traction. We meet the Rhinemaidens as waitresses at a holiday swimming camp for children. Alberich, a wolfish Olafur Sigurdarson in jeans and black leather jacket, is a low-life who steals one particular child. The quest for youth has replaced the quest for a gold ring. In place of archaic swords and spears, our gods and demi-gods wield cell phones and handguns. When Wotan and Alberich simultaneously point guns at each other they are sealing their mutual fate as conjoined rivals in the quest for youth.

[Alberich kidnaps the young Hagen to the frustration of his evil son Mime, sung by Arnold Bezuyen.

And some of the director’s tinkering never gains traction, such as an interminable food fight by an imprisoned child (future villain Hagen) going on upstage during the early encounters between Wotan and Alberich. Annoying is an understatement. As is the prophetic Norn deconstruction in Götterdämmerung, in which the three singers are placed too far back to be intelligible, while grotesquely costumed like sequined underwater monsters in a Hollywood B horror film.

All in the Family

Equal parts Tolstoy and Netflix, Schwarz’s Ring underscores the timeless mundanity of every human drama. No longer anchored to the horned helmet tradition, this Ring is about a dysfunctional family, its dysfunctional progeny, the incestuous desires seething just under the surface, and the brief immortality of sexual fulfillment. As relevant as today’s Dow Jones index.

[Wotan and the family of the gods squabbling about Valhalla]

[Wotan and the family of the gods squabbling about Valhalla]

Schwarz’ premiss of the quest for youth as the driving motivation for dramatic action was already contained in Wagner. Freia’s apples keep the gods young, and the deals made to maintain this narcissistic nourishment embroil Wotan and his narcissistic offspring throughout the four operas. It was all there in the libretto. Schwarz’ simply tugged on a few fresh narrative threads.

[Brunnhilde, Catherine Foster confronts Hagen, Mika Kares]

[Brunnhilde, Catherine Foster confronts Hagen, Mika Kares]

The most successful music/setting episode for me was the last act of das Rheingold, and the beginning of die Walküre. Wotan, Fricka, and the demi-gods are bickering about the Freia situation (as if in a lost episode of Succession) when up pulls a car carrying two thugs with handguns. These are the giants Fafner (Tobias Kehrer) and Fasolt (Jens-Erik Aasbø), both deliciously slimy and in rich voice. Our Wotan (a lusty Tomasz Konieczny) complains about the Freia mess he’s forced to clean up, reaching for another cocktail whenever he can. Equally spoiled is his bling-covered wife Fricka, handsomely accomplished by Christa Mayer, always reminding him of the promises he’s made.

Handguns (the sword surrogates), bristling with Freudian symbolism in any context, become the tool of accusation for each character, as well as a means of removing unwanted impediments: Siegmund, for one. And ultimately, the non-heroic super hero, Siegfried.

[Sieglinde, Elisabeth Tiege, first meets Sigmund, tenor Klaus Florian Vogt]

[Sieglinde, Elisabeth Tiege, first meets Sigmund, tenor Klaus Florian Vogt]

Outstanding singing throughout all four operas overcame moments of silly staging dependent upon too many plastic dishes and endless cocktails. Making her Bayreuth debut, Norwegian Elisabeth Teige as Sieglinde was every bit a match for superstar Klaus Florian Vogt’s Siegmund. Vogt keeps growing as an actor as well as a singer, but the new Sieglinde here made a notable Bayreuth debut. Her performance in the third cycle provided a true star-is-born experience. Passionate and dextrous as an actress, she matched Vogt’s crystalline crescendoes with gleaming colors and persuasive phrasing, especially in the middle of her impressive tessitura. Still messing with time, space and our expectations, Schwarz’s Sieglinde as already pregnant when we meet her. We can’t be sure just who the father is. Does time move backwards? Why not?

One of Schwarz’ most successful staging inspirations is to have characters arranged simultaneously, i.e. poetically, rather than showing up one after the other in narrative fashion. Servants in Wotan’s estate continuously picking up, cleaning up and offering food and drink. One of the serving women suddenly drops an entire tray of drinks. And at that moment she steps into the role of Erda, whom Wotan pleads for advice. She warns him that he’s going to have to take responsibility for what he’s done, all the women he’s had sex with, all the corners he’s cut in order to get what he wants. And just as suddenly she re-enters the cocktail party of the gods, overseeing a team of maids to clean up the floor. Effective stagecraft, it both condenses cumbersome scene changes, and reminds us that everywhere in Wagner, Time becomes Space.

The device of having characters, and even actions yet to come, placed onstage simultaneously is most stunningly realized in the second act of Siegfried, where Fafner—now a feeble old man on life support—is being cared for in a luxury nursing home. Fafner is already close to death. It doesn’t take a hero to kill him. There are no heroes in Schwarz’ Ring, only ordinary mortals nursing their entitlements. At the back of the set, Alberich and Wotan sip cocktails next to each other. In the front of the set, Siegfried and Mime, fresh from the revelations in Mime’s mancave, perch on a couch with Hagen, now a teenager, dressed in the same yellow shirt and blue pants as the stolen child in the opening of das Rheingold. A young attendant, weary of feeding the aging Fafner, relaxes on the couch and begins flirting with Siegfried. The music alerts us that she is the Waldvogel who then begins to sing of Mime’s true intentions and Siegfried’s danger. The economy of storytelling by collapsing sequential time into spatial simultaneity pumps energy into an opera that can weary even diehard Wagnerites.

The device of having characters, and even actions yet to come, placed onstage simultaneously is most stunningly realized in the second act of Siegfried, where Fafner—now a feeble old man on life support—is being cared for in a luxury nursing home. Fafner is already close to death. It doesn’t take a hero to kill him. There are no heroes in Schwarz’ Ring, only ordinary mortals nursing their entitlements. At the back of the set, Alberich and Wotan sip cocktails next to each other. In the front of the set, Siegfried and Mime, fresh from the revelations in Mime’s mancave, perch on a couch with Hagen, now a teenager, dressed in the same yellow shirt and blue pants as the stolen child in the opening of das Rheingold. A young attendant, weary of feeding the aging Fafner, relaxes on the couch and begins flirting with Siegfried. The music alerts us that she is the Waldvogel who then begins to sing of Mime’s true intentions and Siegfried’s danger. The economy of storytelling by collapsing sequential time into spatial simultaneity pumps energy into an opera that can weary even diehard Wagnerites.

[Siegfried, Andreas Schager discovers his love Brunnhilde]

[Siegfried, Andreas Schager discovers his love Brunnhilde]

In the second act of Siegfried the cast had succeeded in mapping the myth onto the dreams and petty desires of ordinary, flawed people. We meet the still sleeping Brünnhilde not encircled by fire, but cloaked and wrapped in gauze. Slowly Siegfried unwinds her bandages—a terrific stand-in for armor and helmet—and reveals a new woman, no longer the superhuman Valkyrie, but a fully human individual.

Schwarz’ suggestions that his performers bring their own personal attitudes and gestures onto the stage works so well that all four operas cohered into a believable and complete world, passionately shared by the players. They believe in their pet squabbles and dynastic baggage, and so do we.

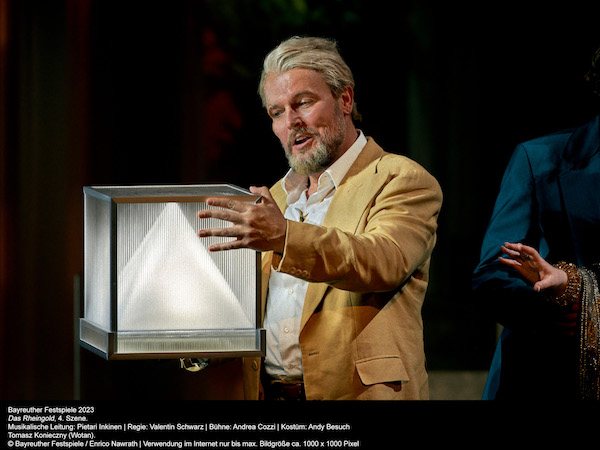

[Wotan, Polish bass/baritone Tomasz Konieczny]

[Wotan, Polish bass/baritone Tomasz Konieczny]

Flawed God, Charismatic Singer

In this production Wotan is a lout, a self-centered decadent, hellbent on pleasing himself, even if it means peeking up family skirts. Incest themes, already abundant in Wagner, are reinforced at every opportunity. Everyone is Wotan’s offspring or lover, and the ultimate couple are indeed aunt and nephew. Catherine Foster, as Brünnhilde in Walküre seemed more at home in her role as the youth-seeking god’s favorite daughter than in productions past. Stomping around in fringed leather jacket and boots, she both loves and hates her father. Her rebellion against him was antagonized by their fiercely ambiguous embraces and his curling up in her lap. Even though it gives Schager, in the final act, a chance to fully unfurl his seemingly tireless voice, die Walküre was commanded by reigning Wotan, Tomasz Konieczny, a bravura actor capable of fierce vocal power and emotional range.

His voice, especially in the velvety, rounded lower edge of the baritone range, was explosive from start to finish. His bitter denouncing of Alberich, the octave leap in which he declares das Ende! attacked the operahouse like a bolt of lightning. And the finish of his harrowing Leb’ wohl farewell to Brünnhilde, when he finally, fully grasps what has happened, was breathtaking. His robust voice now spent—as he made us believe—he crumpled to his knees, and while the entire house grew hushed, he sang-whispered the loss of his dynastic dream. Sheer magic, and the performance of a lifetime.

From his recent triumph as at the Met as the Hollander, to the many Wotans in European halls that have honed his confidence in the role, Konieczny is in the prime of his stardom. His charismatic Wotan in this 2023 Ring gave lucky audiences everything they came for. Clad in a Naples yellow suit and sexy platinum haircut longer on one side to suggest the missing eye, Konieczny’s Wotan was a swaggering flawed pater familias, as troubled and petulant as any of his children or siblings. He drinks, he lusts, he bullies, and he drinks some more. Instead of leading his bickering family proudly across the rainbow bridge at Rheingold‘s end, Konieczny literally danced his way through the final bolero alone, on a balcony high over the stage. Reveling in his own fantasy of Valhalla, in a moment of electrifying stagecraft.

[Brunnhilde comforting her distraught father Wotan]

His tremendous baritone roams a wide emotional frontier, from tenderness to ferocity with equal ease. Reaching down to a velvety, growling bass, he was capable of floating the long vowels at the top of his range before biting off the final consonants. The rage of his Wotan filled the entire hall during the final moments of die Walküre. A compelling actor, a ferocious singer, who looks every inch the tortured god—he is exactly what Wagner had in mind.

So much works in the first three operas, that the final setting of Götterdämmerung proves jarring. The castle of Gunther and his sister Gutrune, along with half-brother Hagen—now fully grown and performed with pungent angst by Mika Kares—is another version of the featureless nouveau riche estate in which Wotan’s Walsung clan swilled their booze and aired their resentments. Action pivoted around a large white couch, on which Gunther, played with irritating antics by Michael Kupfer-Radecky, an over-sexed loser with long blonde hair and tight leather pants, throws pillows back and forth with Siegfried. Gutrune was realized successfully by Aile Asszonyi as a brainless blonde bimbo, with whom Siegfried quickly becomes sexually intoxicated.

Once the betrayed Brünnhilde makes a deal with Hagen and Gunther to put an end to Siegfried, the last scenes, set in the bottom of a drained swimming pool, added another layer of confusion to Schwarz’ ambitions. Echoing the swimming pool opening in which we first met the Rhinemaidens, here even the Rhine has dried up.

[Elderly Rhinemaidens attempting to seduce Siegfried]

[Elderly Rhinemaidens attempting to seduce Siegfried]

The desperate trio attempting to seduce Siegfried and kidnap his child, are aged hags clad in designer suits. Everything is winding down, dying, ending, except the young child who manages to climb up out of the pool. Setting the death of Siegfried and the self-immolation of Brünnhilde in the bottom of an empty swimming pool is a tasty idea that failed to translate into any stage magic. Visually barren, the setting threatened the glorious thunder of the finale. Here maestro Inkinen kept the music restrained, although you sensed the strings and horns were primed to be unleashed. I longed for a bit more sturm und drang in the orchestral ascendance, a release into the grand musical gesture that would reunite the entire cycle back into its origins. The failures of each generation to move beyond themselves, to make room for the future are crafted with vision and audacity by Valentin Schwarz. What is needed is a more shapely mis en scene equal to the concept.

Schwarz’ key decision was to eradicate the dichotomy of gods and mortals. Wotan’s narcissistic patriarchy is mired in situations we all know well—Dynasty meets The Apprentice, with shadings of HBO’s Succession and Shakespeare’s King Lear. There is no lofty kingdom of the gods. We’re plunged into a world already down and dirty, grasping for youth and territory, utterly irresponsible in its actions. Brünnhilde rejects Wotan. Siegfried overpowers him. There will be no Valhalla.

Workshopping can tweak the set designs and staging to give more support to Schwarz’ vision. The director succeeded in plunging the Ring characters and their motivations fast forward into our own fears and unvoiced desires. We grasp at any way we can to stave off our end. Living through grandchildren. Acquiring wealth and property. Refusing the ravages of age in all the ways that science and surgery can provide. The fear of the end, and not only the end of the Valhallan dream that Wotan must confront, but the end of our own lives as well, gives this Ring its psycho-mythic center.

Missteps and all, it is a vision worthy of Wagner.