Three days after the last rolling waves of the Rhine river had dissolved into thin air, the music stayed inside my body. All of the themes of Richard Wagner’s opulent masterpiece resound. They’ve seeped into me through the surge and flow of the four operas that sum up his epic vision of greed, love, power, the gods, and humanity itself. I can still hear the Rhine maidens tempting the evil dwarf Alberich, and feel the sparks and flint of his anvil forging the gold into instruments of malecious magic. The much-parodied, still overwhelming theme of Brunnhilde and her Valkyries, the sad majesty of Wotan, doomed lord of the ring and father of the gods. Siegfried‘s horn, the dragon Fafner‘s thundering mischief, the sparkling flicker of Loge, the god of fire. With luck, the music will stay and sing to me for another few weeks, until it gradually releases me from its spell.

The music not only powers the great mythology of Wagner’s Ring, the music is the saga itself. At least in the hands of maestro Peter Schneider and the consummate orchestra of the Vienna State Opera I heard this summer. Performing on the exact instruments Wagner specified,( and in the case of the Wagner horn, whose sound resembles a cross between a trumpet and a trombone, an instrument Wagner himself designed) this orchestra created the sonic bridge that took last May’s audience from the 19th century hall to the edge of Valhalla itself.

But the orchestra had help. A solid cast of singers—notably a wickedly affecting Wotan (Tomasz Konieczny), a marathon heldentenor Stefan Vincke as Siegfried, an occasionally breathtaking Petra Lang as Brunnhilde as well as two marvelous villains in the form of Ain Anger as Hundig and Falk Struckman as Hagen.

It’s a rare and costly enterprise to commit to a cycle of The Ring’s four operas—”four long operas” —in this case involving a stretch of 10 days and 16+ hours of onstage performance. To explain to a Wagner virgin that you are actually going to submit to that many hours of sitting, listening, and watching is to sound off one’s rocker. But to Wagnerites, this endurance contest is life-giving.

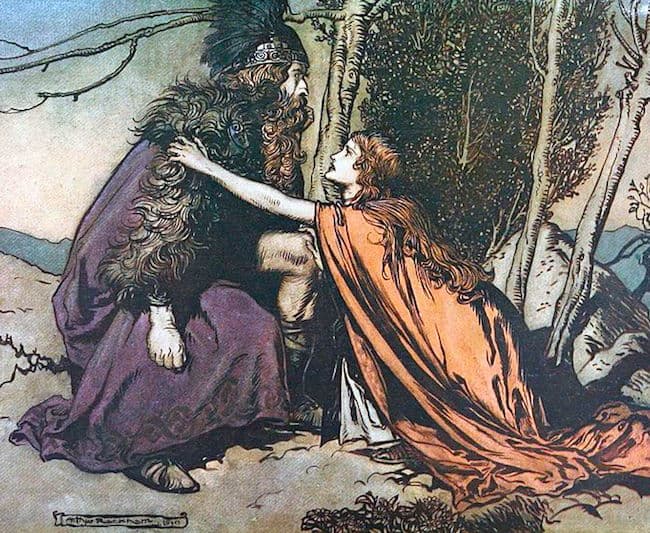

Once you’ve heard all four operas in close proximity, e.g. Seattle and Bayreuth perform the four operas over a brisk seven day period, you are changed forever. Each individual opera forms a poetic whole and yet points onward to the next one. The final piece, Gotterdammerung, revives all of the musical gestures, emotions, and motifs of the previous works. It both concludes—as only the destruction of Vallhalla can—and yet it lives on within the viewer. The Valhalla theme—a triumphant bolero—is a glorious, and yes, catchy motif. Less than a day after the final French horn had sounded, I was planning my next “Ring.” It is a journey in which there is no conclusion, there is only endless transformation.[below: Tomas Konieczny as Wotan.]

Wagner’s Ring amounts to a theatrical version of the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. We are all pilgrims, journeying through the voices, the stagecraft, the soaring instrumentation, the multi-dimensional myth, en route to a holy shrine. And yet the route in this case is the shrine, and every note is a sacrament.

Wagner’s Ring amounts to a theatrical version of the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. We are all pilgrims, journeying through the voices, the stagecraft, the soaring instrumentation, the multi-dimensional myth, en route to a holy shrine. And yet the route in this case is the shrine, and every note is a sacrament.

Back to the performance. The opera as a complete work of music-theater belongs, as it must, to Wagner. He gives us a morality play disguised as a fairytale (Rheingold & Walküre). Much of the libretto makes no sense, but once the very first long measures of Rheingold begin, we simply don’t care. It is all about the music! A glorious orchestra, each section—strings, brass, harp—better than the next, dove deeply into the mind of Wagner and emerged with a steady outpouring of ecstatic darkness, shimmering topnotes, plush chromaticism powered by unerring virtuosity. The musicians seemed connected to both the conductor and the singers by an organic web. Utterly convincing. So perfect were the upward movements, the crescendoes, that even the high notes of trumpets seemed made of new colors.

Some specifics about this Vienna Staatsopera 2017 production, reviving minimalist but effective staging and sets by Sven-Eric Bechtolf. Small details brought this Ring to moments of great clarity and resonance.In Rheingold, as Wotan fights for possession of the gold ring with the Niebelung Alberich, (Jochen Schmeckenbecher) the stagecraft shows us the two mythical opposites—king of the Gods, and underground-dwelling dwarf—joined by a single crimson cord. Their tug-of-war visually reminds us of how they are united in their greed, and whoever wins the gold, will lose it in the end. That single red cord, the width of the entire stage, was arrestingly eloquent of the Nietzschean tension in these opposing characters.

Some specifics about this Vienna Staatsopera 2017 production, reviving minimalist but effective staging and sets by Sven-Eric Bechtolf. Small details brought this Ring to moments of great clarity and resonance.In Rheingold, as Wotan fights for possession of the gold ring with the Niebelung Alberich, (Jochen Schmeckenbecher) the stagecraft shows us the two mythical opposites—king of the Gods, and underground-dwelling dwarf—joined by a single crimson cord. Their tug-of-war visually reminds us of how they are united in their greed, and whoever wins the gold, will lose it in the end. That single red cord, the width of the entire stage, was arrestingly eloquent of the Nietzschean tension in these opposing characters.

Ironically, I had gone to Vienna specifically to hear the great Welsh baritone Bryn Terfel sing Wotan. He cancelled at the very last minute, and Konieczny stepped in. It turned out to be a great act of fate. Konieczny is not only an attractive and dynamic stage presence, but his honeyed voice lent endless color variations to Wagner’s innovative passages powering Wotan’s existential struggles. A tremendously effective actor, Konieczny’s farewell to his daughter Brunnhilde had the audience in tears. Never before had I grasped the depth of this father’s pain upon releasing his much-loved daughter of her immortal status. In her shameful mortality, we glimpse the beginning of the end. It was a scene I will never forget.

Götterdammerung, the last and longest (6 hours, including two intermissions), did not disappoint. Petra Lang dropped her annoying physical mannerisms—the petulant facial mannerisms, the clenched fists—and stepped confidently into the persona of the mythic Valkyrie, Wotan’s favorite daughter, and became the beloved wife of fallen hero Siegfried. She was magnificent, her voice strong, soaring, often beautiful in its burnished and rich mid-tones. As she sang farewell to her father, and to his dreams of an immortal Valhalla for all the heroes, she was both bitter and heartbroken. Be at peace, she sings to her absent father. Ruhe, o gott—Rest, oh god. In the end, I was convinced by Lang, a brilliant if not charismatic Brunnhilde.

Her Brunnhilde is Adam, disobeying God and paying the price: the loss of Eden, loss of heaven, loss of immortality. Yet she gained the ability to love, something that Wotan sacrificed in order to possess the ring. While Stefan Vincke’s Siegfried had vocal stamina to burn, his tendency to grin inappropriately (perhaps he thought he was playing Parsifal?) robbed many key moments of their power.

Wagner’s Ring is a sacred journey that binds all those who travel it in a deathless fellowship. A fellowship of the ring. The music continually makes us an offer we cannot refuse.

Months later, I am still filled with the power of Wagner’s music—an incomparable achievement in artistic vision. Bravo to the magnificent Vienna Philharmonic orchestra, whose empassioned expertise reforged this Ring with elegance and power.

Lovely write-up, Christina. Yes, it is indeed difficult to explain to non Ring-heads the effect this magnificent and profound work has over us. But you do a great job! Wish I could have seen it.