Strapped in and thoroughly prepared for the rippling arpeggios and sonic repetitions that are Philip Glass’ prevailing strategies, I was surprised and transported by the majestic themes and counterpoints of his new opera, Appomattox, at its world premiere last week at the San Francisco Opera. At the baton was an old friend and long-time Glass colleague, Dennis Russell Davies, who commanded every nuance and thundering key change of this gorgeous piece of music.

majestic themes and counterpoints of his new opera, Appomattox, at its world premiere last week at the San Francisco Opera. At the baton was an old friend and long-time Glass colleague, Dennis Russell Davies, who commanded every nuance and thundering key change of this gorgeous piece of music.

Davies, believe it or not, was making his SF Opera debut — a long overdue debut for such a consummate interpreter of new music. Davies deserves a major world orchestra, but that’s another story.

The setting offered much dramatic promise — the final days of the Civil War, and the delicate negotiations of surrender between Robert E. Lee (sung by Dwayne Croft) and Ulysses S. Grant (Andrew Shore). Thanks to the magnificent baritones, an unusual touch, as the generals, the poignant scenes of battle fatigue and civility after four years and 600,000 confederate deaths, were subtle and moving.

However Glass and his librettist Christopher Hampton, ever postmodern, introduce not only events of today’s civil rights struggle into the midst of the Civil War — but even interlace the evening with a bathetic anti-war tract — and hence neutralize the aesthetic power of his music.

Thinking that we were in for an all-male evening of north vs. south dramatization, the audience was surprised by the opening scenes in which the wives — Julia Dent Grant, Mary Custis Lee and Mary Todd Lincoln, as well as female members of the chorus portraying citizens, slaves, wives and mothers — set the stage for the action by articulating the psychological back-stories of the President, the generals and the war-weary country. These early scenes were beautifully performed, sung and, again thanks to Glass’ elegant score, deeply affecting.

Much too much dead space in both acts, however. Moments of sheer silliness — such as the opera chorus (magnificent singing throughout!) crooning “ahhh†as the city of Richmond apparently burned down around them. Another emotional and artistic disconnect occurred during the second act in which the story of civil rights protestor Jimmie Lee Jackson suddenly erupts in the midst of the surrender of 1865. Glass was clearly interested in juxtaposing the possibility of peace represented by the end of the Civil War, with the continued struggle for equality on-going a hundred years later, in 1965. But dramatically, it felt utterly jarring — musically, it was frankly boring. The ending, with the women reprising their caution that this would not be the last war, seemed a desperate leap into the obvious on the part of an artist – Glass – who can do much, much more.

Appomattox – a major success defeated by its own inconsistency.

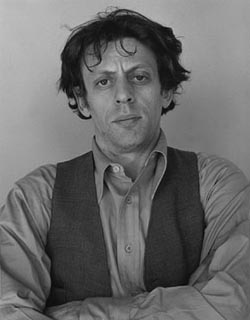

(Robert Mapplethorpe’s photo of Glass, taken in 1976)