by Christina Waters | Oct 31, 2024 | Art, Home |

What I have to say will come as no surprise.

But it will probably offend many of you.*

These remarks are long overdue—they spring from having seen too many sow’s ears made out of sow’s ears. And too much motherly “support” for the arts that is fatal to authentic art-making. Supporting is condescending. In some cases it amounts to virtue signaling. E.g. I went to the Symphony so that I could say I went to the Symphony.

Being a critic, especially in a small community, is a thankless task. Everyone with a performance, or a concert, or an exhibit seeks critical approval. But few want to hear critical appraisal.

Pro tip: if you consistently tell the truth, if you’re fair in your evaluations, people will trust what you have to say. But if you always praise every performance, every dance recital, every plein air show, etc. etc. no one will trust you.

“But I read a rave review in the __________. ” Yes, but did you believe it? Rave reviews only have credibility if the critic doesn’t give everything a rave review.

I am invited to many openings

And rehearsals, performances, and events. It’s wonderful to be asked. I try to go to ones that my intuition tells me might offer surprise. Pieces that show skill, but even more; that trigger some new insight. Pieces made by artists who can shape a narrative, or produce an unexpected image that points and reveals beyond itself.

There’s always a place for enthusiastic amateurs, people who enjoy making decorative visual work or playing music and who are generous about sharing. Creative people abound where I live in Santa Cruz, and many are self-aware enough to know when the work deserves a professional showing or when it’s wiser to invite family and friends to come admire at a private venue. It takes major chutzpah to charge audiences $30 to see/hear your work. And so the work must be able to justify the ticket price and to bear scrutiny.

Mothers Love Everything

Consider this: My mother loves everything I do, even though as a painter herself she doesn’t mind chiming in with a few choice words about composition or color choices. But my mother is subjective. Mother’s love what their children do. Refrigerator doors display the evidence. A critic is not the artist’s mother.

Be a true friend

If supporting your friend’s artwork means never daring to say a critical word about their efforts, then you’re not only cheating your friend of expanding his/her horizons—you’re lowering the bar of quality for everyone, the insanely gifted as well as the up-and-comers. You’re proclaiming that whatever they do is good enough for you. You’re patronizing your friend. It’s true, you might bruise someone’s feelings by offering a critical comment. But to never risk hurting someone’s feelings is to stay safe and agreeable (and phony!). It’s throwing away the chance to have an authentic discussion, to engage in some nitty gritty about artistic intentions.

Hell yes it’s easier, and safer, to simply smile and tell your friend/acquaintance that their work is “interesting.” That you’re glad you came to see it.

We’ve all done that. In the long run, it’s a sign that you don’t expect much from that person.

True story

My mother’s friend Donna was a woman who made little animal figures out of (so help me) cookie dough mixed with some hardening agent. Donna gave all her close friends one of these little figures for Christmas gifts. My mother, a sweet woman without a single enemy in the world, always complimented Donna on her annual dough figurine. And sure enough, next year Donna gave my mother the exact same species of dough figure. This went on year after year.

My mother had encouraged her friend and she got what she deserved. A cabinet full of kitsch. [After Donna’s death, I opened my mother’s china cabinet, grabbed a half dozen of these misshapen monsters, and hurled them into the garbage.] And Donna, a woman who might have pushed herself to more adventurous results, stayed right where she was on the felt-and-sequin ladder of tackiness (where my late Auntie Da is the reigning matriarch.)

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not knocking the creative urge. It’s a universal impulse, and it’s a lot healthier than vaping or using a leaf blower. It’s done for the sheer love of it. But you don’t ask a critic to come see your new macramé piece expecting a published review.

If you do expect some critical response to work you’ve presented in public, be prepared for honest feedback. Something along the lines of, “Have you considered casting a trained dancer in the role of the acrobat (rather than your arthritic father-in-law)?” or, “This seems like a terrific start to something. If you explore this style further, who knows where it will lead.”

Another pro-tip

As a longtime restaurant reviewer I learned to accentuate the positive. If the food was mediocre, I wrote about the decor. If the food was bad, I didn’t write about it at all. This is a small town.

I will never tell you I loved your work, if I didn’t. If I felt it was unclear, or naive, or cloying, or just plain silly, or that it had been done before many times (and better), I will strive to be polite and say nothing. Lying to someone doesn’t help them grow or introspect about what it is they’re trying to express. It simply perpetuates the ordinary, the easy, or the embarrassing. Or worse. It deludes a serious practitioner into self-satisfaction, rather than encouraging them to go further. We already have plenty of that. We each should be aiming for the stars. But you’ll never aim there if you are consistently told that you already *are* there.

Final pro-tip

Just because someone is a nice person and has put a lot of effort into a piece of work doesn’t make it good. Hard work doesn’t equal insight. Quantity does not equal quality. A critic who refuses to coo platitudes is actually encouraging artists to push further. Those who come out to support are like mothers showing up for their child’s recitals. They are doing their duty.

To unreflectively applaud everything is to fail the entire mission of artistic growth. Those who come out to support don’t engage with the work, or the artist. They neglect to educate themselves in the history or vocabulary that would help to stretch and strengthen their own insight into what the artist is doing. They stick to safe, feel-good categories. “I love your colors,” or worse. They simply walk through an exhibit, or sit for a concert, without bothering to assess or discuss what they’ve just seen and heard.

Don’t be that kind of art consumer. Ask more of yourself. And of the artist.

Stop supporting the arts. It’s condescending! Authentic art doesn’t need to be supported. Go because you expect to be excited, swept away, surprised, delighted, and impressed. To have a good time, not to be worn out by obligation.

_______________

* This piece was prompted by my recent experience of an art “event” so utterly misguided, embarrassing, and narcissistic as to be almost beyond comprehension. Rather than ruin someone’s day, or indeed their art practice revival, I sat there and endured an hour I will never have back. The other observers were there to “support” the artist’s effort, which was not a pro bono affair. A hefty chunk of change was charged. I was appalled and insulted. Hence this post.

Food for thought: Does Patti Smith need your support? Or a concert by professional musicians? Or a play by Shakespeare? Would you go hear Jonathan Franzen read because you want to support him?

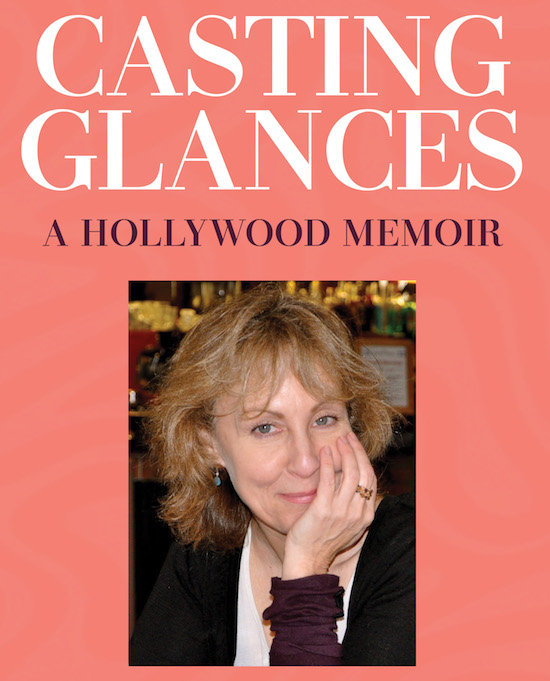

Casting Glances: Odyssey of movie maker Judy Bouley

by Christina Waters | Sep 26, 2024 | Book, Home, Movies |

It’s been a long and winding road from Santa Cruz to Hollywood to Kazakhstan and back, but casting director Judy Bouley brought back hair-raising, spine-chilling, and joyous tales from her life in the movies. Casting Glances is the name of her just-released book—soon to be available on Amazon—and it’s loaded with tell-all back stories of Hollywood stars, extras, exotic locations, triumphs and screw-ups. But more than simply a collection of cinema gossip and rich travel lore, Bouley’s book boldly documents her own over-the-top professionalism, its implosion into emotional crisis, meltdown, healing, and ultimately post-COVID reality.

Having known Judy since our early acquaintance as founding members of the Santa Cruz Film Council some 40 years ago, I was eager to talk to her about the new book.

Q: I found it fascinating that a casting director doesn’t simply go out look for the right actors, give them to the director and the production team, and then move on. What happens once you find what you think are the right actors?

Bouley: Well, I work differently than most casting directors who hang out a shingle and have an office in Hollywood or New York and they don’t ever travel on location. I always stay with my films. People assume that we cast all the actors and extras before filming begins. Not true. I’ve had directors make revisions in the script and I was given 48 hours to find the right actors. They called me Mama Bouley on Master & Commander because I was always there for the background artists.The reason I stay on the set is that you never know—the director could have a new idea on Thursday, and you have to cast and be ready to go on Monday. I first got into casting with Lost Boys in Santa Cruz. I cast five speaking parts and 2200 background parts. And I did Star Trek IV and five films with Tom Hanks. The work is about relationships. Once they trust you the work starts flowing.

On The Polar Express we had thirty six cameras placed all around the set, digitally recording, many times per second, a 360-degree view of the actor’s movements. That digital information was collected via the sensors and then fed to a team of computer wizards who transfered the actors’ movements to a 3D model.”

Then they started flying me around. And then I ended up in Bulgaria, Morocco, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and I spent eleven months in Mexico on Master and Commander. I was there all the time to put out any fires before they started.

“My staff booked over two hundred men and boys for auditions in San Diego alone. From February to May we held casting calls in Baja, Los Angeles, Santa Cruz, Vancouver and Toronto. In all we processed close to a thousand hopefuls to cast fifty five main crew for Her Majesty’s ship, sixty ‘B’ crew for our battle scenes and two hundred and fifty French sailors.”

Bouley worked for almost a year, living on location, with the cast and crew of Master and Commander, directed by Austalian legend Peter Weir.  (Weir on right, with his cinematographer Russell Boyd.)

(Weir on right, with his cinematographer Russell Boyd.)

Q: How did that work? the huge old ship, huge cast and crew?

Bouley: We bought that ship in Rhode Island for $800,000 and we sailed it to the Panama Canal. Oh, my god, yeah. The real ship lived in Ensenada and then we built an identical ship in the tank that they built for Jim Cameron with Titanic. And then we put it on a gimbal, that’s a machine that moves the ship from left to right. It’s amazing. Maybe 150 construction workers built the replica ship, and then they cut it in three parts, and then they used the world’s biggest crane, and they put them in the tank, and then filled it with 600,000 gallons of water.

Q: You’ve had such a fascinating career working with iconic directors and actors, Robert Zemeckis, Peter Weir, Tom Hanks, Russell Crowe, Meryl Streep. Looking back do you think the pace of international assignments and deadlines burned you out?

Bouley: Absolutely. I’ve had an astounding four decades, and I’ve always been hired for the big ones and the hard ones, but it was a lonely existence. You live in the hotel, and then you get extra dirty underwear from Buenos Aires to Morocco. You get off the plane, and you do it again. And sadly, Christina, I did sort of out of sight, out of mind, where I’d only Skype my mother maybe every three weeks. Because, as you know, on a movie set, it’s this temporary intimacy with with everybody. You make them your temporary family. I was married to my career. If I could do it again, I’d do it differently.

“No matter where we were stationed, on the first day of school Mom reminded us, “Don’t get too close to your new friends because either their fathers or your dad will likely be transferred to their next assignment. You’ll just have to say goodbye. It’s better not to get close than to be broken hearted. Through most of my adult life I continued to carry out my mother’s questionable instructions. This contributed in part to my unsteady love relationships in which I had one foot in, one foot out. ‘Nice to meet you, where’s the exit?’ My father taught me to always keep my passport current and never own any more than I could pack in an afternoon.”

(Bouley, with young extras in India.)

(Bouley, with young extras in India.)

Q: The book also reveals intimate details of a lot of personal traumas and things suddenly breaking down with your longtime partner.

Bouley: I suffered through nine deaths. I helped every one of them through, through their death. I did The Way Back with Colin Farrell and that was my last one. That was three and a half years ago. There was COVID, and then there was the strike. And you would have thought that there would have been a collection of film offers on the table after that, but the studios aren’t into film anymore. They’re conglomerates. Universal is owned by Seagram, and they make a lot more money selling scotch than they do making Master and Commander.

(Bouley with actor Colin Farrell in Weir’s The Way Back)

(Bouley with actor Colin Farrell in Weir’s The Way Back)

Q: What did you want to do when you grew up?

Bouley: I wanted to be a social worker, which I was in Santa Cruz. I worked for Child Protection, and then I got laid off. That was in the mid-80s. So I went back to waiting tables at Cardinales on the wharf, and teaching jazzercise.

I got into this business because I volunteered for the Santa Cruz film festival, when Lost Boys came to town. They needed a location scout so they called Chamber of Commerce, and they called me. And I got paid $75 a day, and I got to wear a walkie talkie. In a way casting was still like doing social work, just using the vehicle of film. You can’t stay for 40 years with Child Protection, it’ll burn you out.

I met my business partner Dick Broder on the set of the Santa Cruz-based independent film Hard Traveling.

“I was doing the job of three people on the film: casting, props and catering at the whopping rate of $250.00 a week…essentially slave wages in the film business, even in 1984. “Hard Traveling” was a great crash course in what ‘not to do’ in film-making. Things on set were a chaotic mess. The assistant director was not pushing the director to stay on schedule. The director, being the director, wanted things his way. No one communicated well. The producer, was in over her head. In a word…messy.”

Q: How central was your stay at the Professionals in Crisis program at the Menninger Treatment Clinic to your ability to stabilize your career and self confidence?

Bouley: The mental health program at Menninger saved my life. The Professionals in Crisis program. I was in the program with 20 other people, including the CEO of NutraSweet, who showed me his $40,000 Rolex. So that proves he’s crazy. And Marissa Tomai’s boyfriend. That was when Peter Weir (my favorite director) hired me for The Way Back which we filmed in Bukgaria, Morocco and India. I also cast in Kazakhstan and Krygzystan for that film.

“At Menninger we had to eat three meals a day whether we wanted to or not. For the first week an aide sat next to me to make sure I chewed and swallowed. We were weighed twice a week. I came in at 99 lbs.”

It was right after my business partner, Dick, my best friend for 14 years, committed suicide. I had been on Road to Perdition shoot in Chicago for eight months, and we were literally shooting this scene where Tom Hanks kills Paul Newman, And then my phone rang, and it’s a detective. They found Dick in a hotel room. And, yeah, jeez. I couldn’t go back to film right away. It took me about 4 years to feel ready to go back to casting.

Q: I know you worked on this book for many years. And you include a memoir of your relationship with Dina Babbiott. How did that come about?

Off and on, it took 14 years to write this. You remember Dina Babbitt, who as a girl had been an artist in Auschwitz? She was living in the Santa Cruz Mountains at the time. Well Dina was really my Obi Wan Kenobi and we met when I lived with John (my cocaine addict, alcoholic Santa Cruz boyfriend). We met at an animation film festival. And then I lost track of her when I went on location, and then I was back in Santa Cruz and we reconnected, and she said, What’s your next movie? I said, I’m going to write your story. And she said, No, a lot of people have tried, and it was shitty. So I said, Well, it’s not going to be because I know you. We spent four months with me recording her, and practically living with her. But ultimately, it never got made.

I think the reason everybody can identify with this book is, ultimately, it’s a phoenix rising from the ashes story.

Q: What’s next? Will you continue with films, with casting?

Bouley: That’s what I’ll do. There’s usually 100 projects in Los Angeles. But you know, since COVID and since the strike, there are only seven feature films right now in Hollywood. Other places offer better tax incentives, like Boston, Atlanta, Canada and New Orleans.

Still, yes, it’s all I know how to do,

SF Opera Takes on Steve Jobs

by Christina Waters | Sep 29, 2023 | Home |

A Feel-Good Gloss on the Life of Steve Jobs

The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs – San Francisco Opera – September 2023

Part Disney, part Broadway, and surprisingly enjoyable, the musical theater scored with Hollywood dazzle by Mason Bates to text by Mark Campbell will appeal to new opera audiences, as well as skeptical veterans. San Francisco Opera‘s opening week matinee found a packed house entranced by nimble minimalist sets and the speedway pace of the one hour forty minute bio-opera about a hometown titan. In approaching a tough assignment—crafting a short musical work about a global celebrity, famous in life, famous in death—two obvious paths suggest themselves: take a pivotal moment in the life of the inventor and generate emotional depth, or, surf the entire arc of a life and skim through the salient features. In choosing the latter course, the librettist short-changed the actors but allowed composer Bates full rein to his eclectic orchestral reach. The richly textured score plunges into full orchestra movements, with top notes of electronica and synthesizer sonics. An acoustic guitar adds intimacy and eloquence in the passages where Jobs the ruthless entrepreneur gives way to Jobs the dying penitent.

The music surges in and through an episodic series of biographical snap-shots, from Jobs’ childhood, to the family garage, the corporate miasma, astronomical wealth (and stress), to his desperate embrace of Zen Buddhism and demise due to pancreatic cancer.

Especially effective are the many passages of Sprachstimme, where for example we watch the young media manipulator Jobs working with his programmer genius partner Steve Wozniak. The two are high on their own ingenuity, the possibilities of this brave new way of communicating they are cooking up in Jobs’ family garage. This scene—one of 19 that comprise the opera—allows for a disarmingly inventive hip-hop duet by the two singers, John Moore as Jobs and tenor Bille Bruley as Woz. Its captivating energy and syncopation bookmark an apex when Apple was in its infancy, and the bloom was still on a creative partnership.

Especially effective are the many passages of Sprachstimme, where for example we watch the young media manipulator Jobs working with his programmer genius partner Steve Wozniak. The two are high on their own ingenuity, the possibilities of this brave new way of communicating they are cooking up in Jobs’ family garage. This scene—one of 19 that comprise the opera—allows for a disarmingly inventive hip-hop duet by the two singers, John Moore as Jobs and tenor Bille Bruley as Woz. Its captivating energy and syncopation bookmark an apex when Apple was in its infancy, and the bloom was still on a creative partnership.

Moving across and around the critical moments of Jobs’ life, the opera embroiders the corporate frenzy with the strained marriage that salvaged what remained of the perfectionist’s humanity. Perhaps in response to the brevity of each scene, the role of Laurene Powell Jobs is reduced to a neglected housewife cliché. Bates has written his best arias around this character, as burnished to high lustre by the voluptuous timbre of mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke. Moving beyond the expected tessitura, Cooke floated extreme top notes with poignant accuracy and duration of pitch. Like each character in this piece, Cooke is given her own signature leitmotif, a cascade of melisma, remarkably melodic, even romantically figured. Bates wrote for her full range, and the lowest pitches sounded as deep velvet as she sang of her sorrow at her husband’s absence, his neglect. Every scene in which Cooke appeared expanded into flavors of honey and cognac, a ravishing sound that made the listener long to hear this emerging superstar in a much larger, more emotionally detailed role.

Since the librettist provided a check list of greatest moments in the life of Jobs—very much as a Broadway musical might have done—there is as much attention to the role of Zen Buddhism in Jobs’ last years as there is in the call and response of Apple employees against the barking commands of Jobs as corporate czar. Here Bates’ famous kineticism pumps itself up with theatrical juice, creating a propulsive back-beat for the frenetic saga of a genius whose imagination shaped the world—iPhone—we live in. The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs serves up plenty of humorous, intertextual comments about how Jobs urged the world to buy his products, even to the point of breaking through the fourth wall and reminding the audience that as soon as the opera was over they would be reaching for their cell phones.

Shades of Sarastro

Another virtuoso turn is the part of Jobs’ Zen mentor Kobun Chino Otogawa, sung with astonishing tonal purity by Wei Wu. Gifted with an earthy deep bass vocal range, Wu gave surprise, gravity, and plenty of clear-eyed wise-cracking to the flawed seeker. Yet how and how much this Zen persona figured in Jobs’ life remained unexamined, as does almost all of his private choices, passions, habits—except for the shadows in which an early paramour (brightly sung by coloratura Olivia Smith) and the daughter cruelly abandoned by Jobs are given mention. Again, the opera covers so much territory in under two hours that we are left with only rumors of motivation and dimension where there might have been authentic emotional texture.

Many missed opportunities remain in the wings of this invigorating, gravitas-free music theater. The opera creators have chosen to sketch the man for whom all of this is named and explored—Steve Jobs—as an eye-of-the-storm cypher. The main action happens around him, rather than by him. But nimble, appealing John Moore as Steve Jobs, aims his baritone into an attractive bandwidth, and while not a gorgeous muscular voice, it is well up to the task in the middle of the range. Given the fairly flat dramatic material, Moore sculpts a persuasive persona and by the end of the program we are in his corner.

Conductor Michael Christie took full charge of the never-better SFO Orchestra, interbraiding the electronica, solo instruments, and full company into a sparkling, dynamic whole with only occasional bursts of crescendo swallowing the voices.

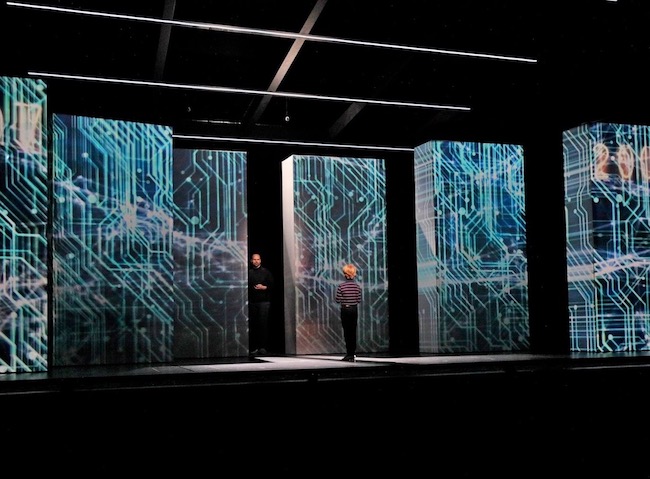

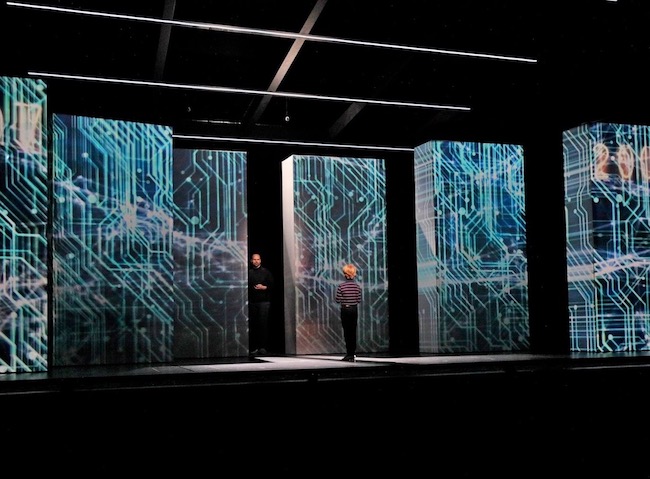

The stars of the very stylish, state-of-the-art production were set design by Victoria Tzykun, lighting design by Japhy Weideman and production design by 59 Productions. The pulsating LED projections of motherboard circuitry rippling across a field of tall screens was dazzling and effective, sweeping us into the heart of the very heart of the miniaturized computers by which Apple became a household name. Flickering references to Tron and Matrix swelled into gorgeous illuminated abstractions throughout the opera. Projected upon six rotating and moveable rectangles, the lighting design propelled the opera into a rare space of pure energy, glowing spectacle leaving the audience itself with a feel-good glow.

If I were the librettist, I’d workshop this production to find a more logical ending place, rather than having the company, led by Jobs wife/widow Laurene, singing Zen affirmations to us, reminding us to “look up, look out, and look around.” Very PBS Special. This is a wordy opera! The true ending might have been ten minutes earlier, freeing up more time for a deepened middle and a more memorable bio-exploration.

Whether there was, or was not enough to Steve Jobs to generate a full saga remains a question mark.

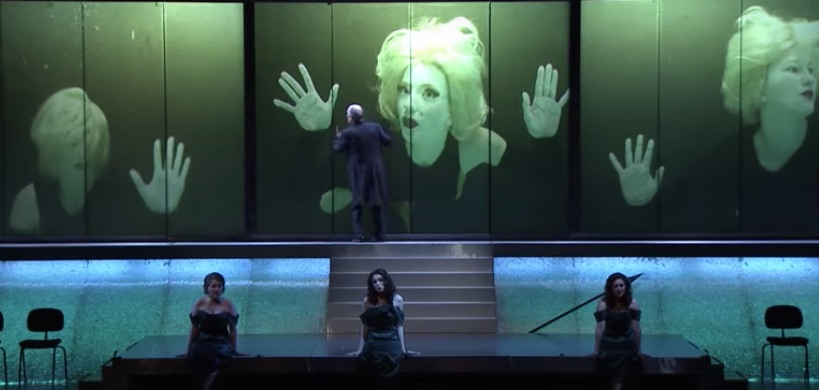

Wagner’s Ring, Bayreuth 2023, Family Feud

by Christina Waters | Sep 6, 2023 | Home |

A Ring for Generation Z

by Christina Waters

As the final Cycle of Bayreuth’s 2023 Ring came to a close, the air remained electric with the sounds of Wagner’s apocalyptic horns and the rapture of the Rhine. [see my Operawire review of the Bayreuth Parsifal here.]Camps came away divided into those either outraged or captivated by director Valentin Schwarz’ reinvention of the gods’ messy journey to oblivion. To be fair, there was much to decry for purists who come to worship at the shrine built by Wagner. In settings that cross-referenced reality TV with darker strains of Freudian family feuds, Schwarz’ imagining of the Ring as a downward spiral of superficial desires and twisted repercussions is bold. And in my opinion both brilliant and prescient. That said, much remains to be fully resolved, tweaked, and workshopped in both the opening das Rheingold and especially Götterdämmerung, the finally opera of the tetralogy. These two opening and closing dramas of Wagner’s epic internecine struggle were so stained with visual non-sequiturs as to practically obliterate the splendor of the score.

[all photos: credit Enrico Nawrath]

[all photos: credit Enrico Nawrath]

The ongoing dissonances that wove throughout Schwarz’ conceptualization of the Ring were both its power and its disenchantment. A prime example was in the shimmering declaration of love and ardor, Winterstürme, Siegfried’s matchless love song to his sister/bride Sieglinde. Perfectly partnered by emerging star Elisabeth Teige as Sieglinde, the golden-toned Klaus Florian Vogt gave full actualization to the role of Siegmund. Yet as the music and Vogt’s voice were soaring through some of the most beautiful love music ever written, the concept was busy tinkering with Elisabeth’s pregnancy, which shows up even before Sigmund does. Splayed awkwardly across a staircase, Teige endured possible sexual probing (or was it the desire to abort the future hero, Siegfried, she is carrying?) by Wotan, even as Vogt lifts his voice toward a perfect world in which the twin lovers will live happily ever after.

The majestic music, lifting and purring securely under the firm control of maestro Pietari Inkenin, never faltered. No matter what the stage narrative told us, Inkenin was armed with understanding of the text and a heroic orchestra, filling the matchless acoustics of the Festhalle. But the visuals had the audience squirming. And this is the key to Schwarz’ vision, for better and worse. Unlike many of the high fashion Wagner productions, such as Herheim’s Parsifal, or Castorf’s Ring, Schwarz doesn’t seem to be simply updating imagery and characterizations in order to shock, provoke, or show off for its own sake. He has an obvious, and—at its best—illuminating vision of a world devolving thanks to the moral bankruptcy of the older generation. In lecture remarks the 34-year-old Schwarz maintained that he wanted not simply to update the Ring, but to make it accessible to today’s audiences. In stage directions cast he asked his cast to sing what the 19th century composer wrote, but to act with their own 21st century gestures and attitudes. As a result this Ring is a literal refreshing of Wagner’s grand motifs. Schwarz gives us a dysfunctional family drama within the post-capitalist rubble of a disintegrating natural world. The real world as we know it!

[Wotan making a guest appearance at Mime’s forge]

[Wotan making a guest appearance at Mime’s forge]

All of which means there is no ring, no Tarnhelm, no gold-hoarding Nibelungen, no horseback Valkyries ho-yo-to-hoing down from the skies. Instead of the Rhine river, there’s a shallow swimming pool. Mesmerizing yet utterly bizarre, the formidable Valkyries are now Beverly Hills housewives recovering from plastic surgeries, all costumed ala Barbie. Schwarz has a sense of humor as well as a concept! Over-the-top Instagram groupies costumed in pink, orange, and red, Wotan’s statuesque offspring laughed, preened and compared breast enhancements, a giggling hell for their profligate father to regret. This Ring is a tale of bad faith with benefits. And there’s not a boring moment in it.

Subliminal Leitmotifs

Wagner’s famous leitmotifs have been shaken up to serve a contemporary reality, and how those motifs shape individual character’s desires also shape-shifts along the way. Instead of a magic helmet, Freia’s shawl is the house fetish carried forward by various characters as a security blanket throughout the four operas. The same for a persistent rocking horse which, as a small toy, as a trinket, as furniture, as Grane, occupies the mis-en-scene throughout. What Schwarz’ recurring symbols mean is not in any way tangible, or defined. But how they have meaning is as clear as the subconscious itself. Moving throughout the four operas is an illuminated pyramid, lit from within, which the various characters hold, or bring with them into the arenas of family feuding. Clearly a cherished object, the pyramid holds our interest and curiosity. No small accomplishment throughout 17 hours of opera!

[Icelandic baritone Olafur Sigurdarson as scheming Nibelung Alberich]

[Icelandic baritone Olafur Sigurdarson as scheming Nibelung Alberich]

Some of this tinkering with our expectations takes a while to gain traction. We meet the Rhinemaidens as waitresses at a holiday swimming camp for children. Alberich, a wolfish Olafur Sigurdarson in jeans and black leather jacket, is a low-life who steals one particular child. The quest for youth has replaced the quest for a gold ring. In place of archaic swords and spears, our gods and demi-gods wield cell phones and handguns. When Wotan and Alberich simultaneously point guns at each other they are sealing their mutual fate as conjoined rivals in the quest for youth.

[Alberich kidnaps the young Hagen to the frustration of his evil son Mime, sung by Arnold Bezuyen.

And some of the director’s tinkering never gains traction, such as an interminable food fight by an imprisoned child (future villain Hagen) going on upstage during the early encounters between Wotan and Alberich. Annoying is an understatement. As is the prophetic Norn deconstruction in Götterdämmerung, in which the three singers are placed too far back to be intelligible, while grotesquely costumed like sequined underwater monsters in a Hollywood B horror film.

All in the Family

Equal parts Tolstoy and Netflix, Schwarz’s Ring underscores the timeless mundanity of every human drama. No longer anchored to the horned helmet tradition, this Ring is about a dysfunctional family, its dysfunctional progeny, the incestuous desires seething just under the surface, and the brief immortality of sexual fulfillment. As relevant as today’s Dow Jones index.

[Wotan and the family of the gods squabbling about Valhalla]

[Wotan and the family of the gods squabbling about Valhalla]

Schwarz’ premiss of the quest for youth as the driving motivation for dramatic action was already contained in Wagner. Freia’s apples keep the gods young, and the deals made to maintain this narcissistic nourishment embroil Wotan and his narcissistic offspring throughout the four operas. It was all there in the libretto. Schwarz’ simply tugged on a few fresh narrative threads.

[Brunnhilde, Catherine Foster confronts Hagen, Mika Kares]

[Brunnhilde, Catherine Foster confronts Hagen, Mika Kares]

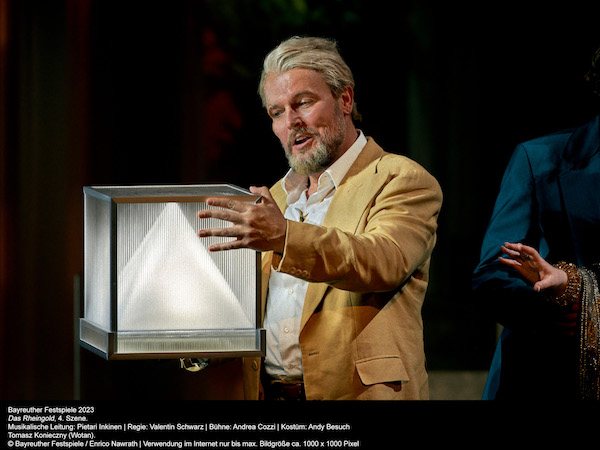

The most successful music/setting episode for me was the last act of das Rheingold, and the beginning of die Walküre. Wotan, Fricka, and the demi-gods are bickering about the Freia situation (as if in a lost episode of Succession) when up pulls a car carrying two thugs with handguns. These are the giants Fafner (Tobias Kehrer) and Fasolt (Jens-Erik Aasbø), both deliciously slimy and in rich voice. Our Wotan (a lusty Tomasz Konieczny) complains about the Freia mess he’s forced to clean up, reaching for another cocktail whenever he can. Equally spoiled is his bling-covered wife Fricka, handsomely accomplished by Christa Mayer, always reminding him of the promises he’s made.

Handguns (the sword surrogates), bristling with Freudian symbolism in any context, become the tool of accusation for each character, as well as a means of removing unwanted impediments: Siegmund, for one. And ultimately, the non-heroic super hero, Siegfried.

[Sieglinde, Elisabeth Tiege, first meets Sigmund, tenor Klaus Florian Vogt]

[Sieglinde, Elisabeth Tiege, first meets Sigmund, tenor Klaus Florian Vogt]

Outstanding singing throughout all four operas overcame moments of silly staging dependent upon too many plastic dishes and endless cocktails. Making her Bayreuth debut, Norwegian Elisabeth Teige as Sieglinde was every bit a match for superstar Klaus Florian Vogt’s Siegmund. Vogt keeps growing as an actor as well as a singer, but the new Sieglinde here made a notable Bayreuth debut. Her performance in the third cycle provided a true star-is-born experience. Passionate and dextrous as an actress, she matched Vogt’s crystalline crescendoes with gleaming colors and persuasive phrasing, especially in the middle of her impressive tessitura. Still messing with time, space and our expectations, Schwarz’s Sieglinde as already pregnant when we meet her. We can’t be sure just who the father is. Does time move backwards? Why not?

One of Schwarz’ most successful staging inspirations is to have characters arranged simultaneously, i.e. poetically, rather than showing up one after the other in narrative fashion. Servants in Wotan’s estate continuously picking up, cleaning up and offering food and drink. One of the serving women suddenly drops an entire tray of drinks. And at that moment she steps into the role of Erda, whom Wotan pleads for advice. She warns him that he’s going to have to take responsibility for what he’s done, all the women he’s had sex with, all the corners he’s cut in order to get what he wants. And just as suddenly she re-enters the cocktail party of the gods, overseeing a team of maids to clean up the floor. Effective stagecraft, it both condenses cumbersome scene changes, and reminds us that everywhere in Wagner, Time becomes Space.

The device of having characters, and even actions yet to come, placed onstage simultaneously is most stunningly realized in the second act of Siegfried, where Fafner—now a feeble old man on life support—is being cared for in a luxury nursing home. Fafner is already close to death. It doesn’t take a hero to kill him. There are no heroes in Schwarz’ Ring, only ordinary mortals nursing their entitlements. At the back of the set, Alberich and Wotan sip cocktails next to each other. In the front of the set, Siegfried and Mime, fresh from the revelations in Mime’s mancave, perch on a couch with Hagen, now a teenager, dressed in the same yellow shirt and blue pants as the stolen child in the opening of das Rheingold. A young attendant, weary of feeding the aging Fafner, relaxes on the couch and begins flirting with Siegfried. The music alerts us that she is the Waldvogel who then begins to sing of Mime’s true intentions and Siegfried’s danger. The economy of storytelling by collapsing sequential time into spatial simultaneity pumps energy into an opera that can weary even diehard Wagnerites.

The device of having characters, and even actions yet to come, placed onstage simultaneously is most stunningly realized in the second act of Siegfried, where Fafner—now a feeble old man on life support—is being cared for in a luxury nursing home. Fafner is already close to death. It doesn’t take a hero to kill him. There are no heroes in Schwarz’ Ring, only ordinary mortals nursing their entitlements. At the back of the set, Alberich and Wotan sip cocktails next to each other. In the front of the set, Siegfried and Mime, fresh from the revelations in Mime’s mancave, perch on a couch with Hagen, now a teenager, dressed in the same yellow shirt and blue pants as the stolen child in the opening of das Rheingold. A young attendant, weary of feeding the aging Fafner, relaxes on the couch and begins flirting with Siegfried. The music alerts us that she is the Waldvogel who then begins to sing of Mime’s true intentions and Siegfried’s danger. The economy of storytelling by collapsing sequential time into spatial simultaneity pumps energy into an opera that can weary even diehard Wagnerites.

[Siegfried, Andreas Schager discovers his love Brunnhilde]

[Siegfried, Andreas Schager discovers his love Brunnhilde]

In the second act of Siegfried the cast had succeeded in mapping the myth onto the dreams and petty desires of ordinary, flawed people. We meet the still sleeping Brünnhilde not encircled by fire, but cloaked and wrapped in gauze. Slowly Siegfried unwinds her bandages—a terrific stand-in for armor and helmet—and reveals a new woman, no longer the superhuman Valkyrie, but a fully human individual.

Schwarz’ suggestions that his performers bring their own personal attitudes and gestures onto the stage works so well that all four operas cohered into a believable and complete world, passionately shared by the players. They believe in their pet squabbles and dynastic baggage, and so do we.

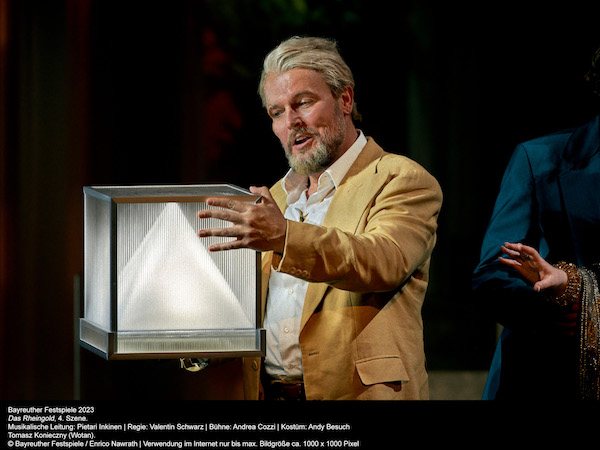

[Wotan, Polish bass/baritone Tomasz Konieczny]

[Wotan, Polish bass/baritone Tomasz Konieczny]

Flawed God, Charismatic Singer

In this production Wotan is a lout, a self-centered decadent, hellbent on pleasing himself, even if it means peeking up family skirts. Incest themes, already abundant in Wagner, are reinforced at every opportunity. Everyone is Wotan’s offspring or lover, and the ultimate couple are indeed aunt and nephew. Catherine Foster, as Brünnhilde in Walküre seemed more at home in her role as the youth-seeking god’s favorite daughter than in productions past. Stomping around in fringed leather jacket and boots, she both loves and hates her father. Her rebellion against him was antagonized by their fiercely ambiguous embraces and his curling up in her lap. Even though it gives Schager, in the final act, a chance to fully unfurl his seemingly tireless voice, die Walküre was commanded by reigning Wotan, Tomasz Konieczny, a bravura actor capable of fierce vocal power and emotional range.

His voice, especially in the velvety, rounded lower edge of the baritone range, was explosive from start to finish. His bitter denouncing of Alberich, the octave leap in which he declares das Ende! attacked the operahouse like a bolt of lightning. And the finish of his harrowing Leb’ wohl farewell to Brünnhilde, when he finally, fully grasps what has happened, was breathtaking. His robust voice now spent—as he made us believe—he crumpled to his knees, and while the entire house grew hushed, he sang-whispered the loss of his dynastic dream. Sheer magic, and the performance of a lifetime.

From his recent triumph as at the Met as the Hollander, to the many Wotans in European halls that have honed his confidence in the role, Konieczny is in the prime of his stardom. His charismatic Wotan in this 2023 Ring gave lucky audiences everything they came for. Clad in a Naples yellow suit and sexy platinum haircut longer on one side to suggest the missing eye, Konieczny’s Wotan was a swaggering flawed pater familias, as troubled and petulant as any of his children or siblings. He drinks, he lusts, he bullies, and he drinks some more. Instead of leading his bickering family proudly across the rainbow bridge at Rheingold‘s end, Konieczny literally danced his way through the final bolero alone, on a balcony high over the stage. Reveling in his own fantasy of Valhalla, in a moment of electrifying stagecraft.

[Brunnhilde comforting her distraught father Wotan]

His tremendous baritone roams a wide emotional frontier, from tenderness to ferocity with equal ease. Reaching down to a velvety, growling bass, he was capable of floating the long vowels at the top of his range before biting off the final consonants. The rage of his Wotan filled the entire hall during the final moments of die Walküre. A compelling actor, a ferocious singer, who looks every inch the tortured god—he is exactly what Wagner had in mind.

So much works in the first three operas, that the final setting of Götterdämmerung proves jarring. The castle of Gunther and his sister Gutrune, along with half-brother Hagen—now fully grown and performed with pungent angst by Mika Kares—is another version of the featureless nouveau riche estate in which Wotan’s Walsung clan swilled their booze and aired their resentments. Action pivoted around a large white couch, on which Gunther, played with irritating antics by Michael Kupfer-Radecky, an over-sexed loser with long blonde hair and tight leather pants, throws pillows back and forth with Siegfried. Gutrune was realized successfully by Aile Asszonyi as a brainless blonde bimbo, with whom Siegfried quickly becomes sexually intoxicated.

Once the betrayed Brünnhilde makes a deal with Hagen and Gunther to put an end to Siegfried, the last scenes, set in the bottom of a drained swimming pool, added another layer of confusion to Schwarz’ ambitions. Echoing the swimming pool opening in which we first met the Rhinemaidens, here even the Rhine has dried up.

[Elderly Rhinemaidens attempting to seduce Siegfried]

[Elderly Rhinemaidens attempting to seduce Siegfried]

The desperate trio attempting to seduce Siegfried and kidnap his child, are aged hags clad in designer suits. Everything is winding down, dying, ending, except the young child who manages to climb up out of the pool. Setting the death of Siegfried and the self-immolation of Brünnhilde in the bottom of an empty swimming pool is a tasty idea that failed to translate into any stage magic. Visually barren, the setting threatened the glorious thunder of the finale. Here maestro Inkinen kept the music restrained, although you sensed the strings and horns were primed to be unleashed. I longed for a bit more sturm und drang in the orchestral ascendance, a release into the grand musical gesture that would reunite the entire cycle back into its origins. The failures of each generation to move beyond themselves, to make room for the future are crafted with vision and audacity by Valentin Schwarz. What is needed is a more shapely mis en scene equal to the concept.

Schwarz’ key decision was to eradicate the dichotomy of gods and mortals. Wotan’s narcissistic patriarchy is mired in situations we all know well—Dynasty meets The Apprentice, with shadings of HBO’s Succession and Shakespeare’s King Lear. There is no lofty kingdom of the gods. We’re plunged into a world already down and dirty, grasping for youth and territory, utterly irresponsible in its actions. Brünnhilde rejects Wotan. Siegfried overpowers him. There will be no Valhalla.

Workshopping can tweak the set designs and staging to give more support to Schwarz’ vision. The director succeeded in plunging the Ring characters and their motivations fast forward into our own fears and unvoiced desires. We grasp at any way we can to stave off our end. Living through grandchildren. Acquiring wealth and property. Refusing the ravages of age in all the ways that science and surgery can provide. The fear of the end, and not only the end of the Valhallan dream that Wotan must confront, but the end of our own lives as well, gives this Ring its psycho-mythic center.

Missteps and all, it is a vision worthy of Wagner.

The Budapest Ring

by Christina Waters | Jul 6, 2022 | Home |

From its first slowly undulating chords to the last sweeping thunder of destruction, Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelungen carries the listener along on an enveloping artistic journey like no other. The opera anticipated cinema and more than captured the composer’s declaration that the four-opera odyssey is indeed “a total work of art”—Gesamtkunstwerk.

It’s a tribute to the magic of Wagner’s vision that in my sixth journey through the 17+ hours of the Ring, I still felt the electrifying effect of the operas as if for the first time. Being swept away by the towering orchestration, the almost impossibly modern conceptualization and sound—so many passages argue for their dates being a hundred years into the future of their actual mid-19th century debut.

This is a work of art that never fails to fulfill expectations. And more. Last month I was treated to the view of the sunset over the Danube four evenings in a row. My experience two weeks ago with the four operas of the hero’s journey and the gods’ downfall unlocked even more secret passages of the great origin saga, not only of northern mythology but of the deep tissue of human psychology, the foibles, vanity, greed, desire, trickery, and love.

The music itself is the storyteller. The stalwart singers often seem to be there simply to punctuate the underlying text which, like the Rhine itself, roils and deepens as it winds through the many strands of fire and water, earth and heaven that ignite the uncanny masterpiece.

Tomasz Konieczny as Wotan: photo Nagy Attila/Müpa

Tomasz Konieczny as Wotan: photo Nagy Attila/Müpa

The story, a sweeping melange of Teutonic myth, Norse fairytale, and dreamscapes from the archaeology of human psychology, tells of the obsession of trolls, men, and gods for a ring of gold, a ring that brings limitless power to its owner. Changing hands over and over—and never by legitimate means—the ring has been forged by gold stolen from the Rhinemaidens, and the course of the operas takes us to the creation of Valhalla, home of Wotan the ruler and his family of gods.

The saga awaits a pure and fearless hero, Siegfried, who can win the power of the ring by slaying a dragon (it’s complicated). He wins the ring as well as the love of Wotan’s Valkure daughter Brunnhilde until greed overcomes his foes, and the gods, Valhalla, and our heroic lovers all go up in flames. And yes, the gold finally returns to the Rhine in the end, with music repeating the opera’s opening musical themes coming full circle in an ending that is both unspeakably tragic and emotionally satisfying.

The four operas unfold over more than 17 hours and in the best possible world there are singers on the stage capable of sustaining a spell throughout those hours. It is a tall order that few can deliver. The charismatic cast for last week’s Ring cycle at the Bela Bartok concert hall in Budapest frequently held the audience in thrall. Stamina, superhuman breath control, and in the case of the soprano singing Brunnhilde, many high Cs even after long stretches of non-stop singing. Many aspire to these roles in the absolute pinnacle of opera.

Nagy Attila/Müpa

Nagy Attila/Müpa

I went to Budapest for two reasons: Wagner, and Wotan as performed by the great Polish bass-baritone Tomasz Konieczny [here with Christian Franz as firegod Loge]. The part of the mercurial king of the gods is arguably the most interesting in a cast of brilliant and volatile characters, including scheming underworld denizens, comedic forest dwellers, jealous goddesses, giants, a dragon, starstruck lovers, and tribal warriors. Wotan—would-be Lord of the Ring—is consumed by the all-too-human desires for endless power and infinite romance. I heard Konieczny sing Wotan in Vienna a few years back and like others in that audience fell instantly under the spell of his brooding and finely calibrated interpretation. Konieczny is a fine actor, a splendid singer, and attractive enough to make you realize just why even the earth goddess herself would fall for him. Possibly the finest Wotan in opera today, Konieczny—in the formal attire—rivals Daniel Craig for tuxedo cred.

Dinner each evening during the second one-hour intermission.

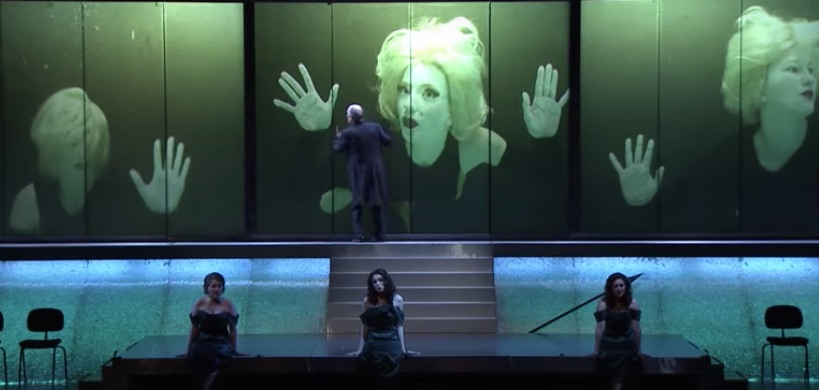

Dinner each evening during the second one-hour intermission.

The semi-staged concept seen in the Müpa Wagner Days productions gave me a new perspective on the Ring. The architecturally brilliant hall is not an opera house. It is a concert hall. That means no proscenium stage, no wings, and no curtain. It is a stage that has been given a few bits of architecture, notably a central stairway leading up to a wide screen on which are projected various atmospheric videos, and around which characters can come and go to suggest changes of scene. The singers all were clad in black formal attire—tuxes for the men, gowns of varying descriptions for women. The orchestra pit was just in front and below the stage, about 20 feet from my raised side seat, a version of a box seat.

The effect of this minimalism was that the opera was immediate and intimate. No sets or built scenery got between the music and the audience. The singers became actual characters in the story, a Singspiel almost in bardic tradition, as much as acted out. In other words, there was nothing to get in the way of the glorious music (except for a troupe of dancers, whose movements echoed the sung story, to mostly distracting effect).

It was my sixth Ring, and with each viewing the story grows clearer and deepens. Wagner is very carefully and lovingly reconstructing the Creation myth of German identity. The story is everything, and it is given the greatest possible music as its vehicle.

Konieczny, a true Helden-baritone is a superb actor, delivering the emotional complexity of Wagner’s vision with expressive body language and vocal nuance. The powerful voice is capable of standing up to the composer’s dense instrumentation. And he can do it for many hours across the operas. As the frustrated god ensnared by his own traps, Konieczny illuminated the eternal truth of Wotan’s passions and regrets. He appears to consider, to negotiate, to weigh the dimensions of everything he’s saying and doing. And yet the singer has performed this role dozens and dozens of times. All the irony and folly, that the gods are only as great as their worshippers, and always as small as their own addictions. comes out clearly. Master as slave.

Konieczny, a true Helden-baritone is a superb actor, delivering the emotional complexity of Wagner’s vision with expressive body language and vocal nuance. The powerful voice is capable of standing up to the composer’s dense instrumentation. And he can do it for many hours across the operas. As the frustrated god ensnared by his own traps, Konieczny illuminated the eternal truth of Wotan’s passions and regrets. He appears to consider, to negotiate, to weigh the dimensions of everything he’s saying and doing. And yet the singer has performed this role dozens and dozens of times. All the irony and folly, that the gods are only as great as their worshippers, and always as small as their own addictions. comes out clearly. Master as slave.

The emotional pivot of the operas happens near the end of the second, and possibly best known of the four operas, Walküre. Angry at her disobedience, Wotan is forced to punish his beloved daughter Brunnhilde, the one who understands and knows him best, by casting her out of Valhalla. Utterly convincing in the heartbreak of a father forced to banish his best-loved daughter, Konieczny delivered indelible tenderness. Here is the beginning of the twilight of the gods, as Wotan’s fierce warrior daughter is suddenly plunged into mere womanhood, made mortal.

As the Brunnhilde for that single night, British soprano Allison Oakes stepped into a genuine star-is-born moment when the original singer, Irene Theorin, was forced to cancel due to illness. Believably vulnerable, defiant, and best of all in great voice she won over fellow singers and the audience as well. Konieczny graciously supported her performance, deferring to her in stage position and in emotional intensity. Tears filled my eyes during their final farewell embrace. It was a brilliant pairing of voices and intuitions and when they came out for a bow at the end of the opera, Konieczny and Oakes hugged each other and bounced up and down with sheer joy at the performance they’d just given.

Many wonderful singer/actors in definitive roles throughout the four operas. A splendid Fricka, much-cuckholded wife of Wotan, sung by Atala Schöck, Nadine Weissmann (singing via video-tech) as the earth goddess Erda, and a persuasive Sieglinde, sung by Karine Babajanyan.

The scheming troll Alberich was performed with delicious bravura by Jochen Schmeckenbecher, the substantial part of comedic villain Mime was sung by Cornel Frey, and the charming giants, by basso-profundos Fafner (Walter Fink) and Fasolt (Sorin Coliban) who were shadowed by enormous puppet surrogates who loomed over the stage while Wotan quibbled over giving the coveted ring in exchange for the captured goddess Freia (Lilla Horti).

But there were production issues, notably the very slick and steep staircase in the centerstage. It allowed performers to change vantage points for dramatic purposes, but it also caused frequent slipping, sliding, and in one case an actual tumble. The atmospheric video displays on the screen at the back of the stage were effective in creating a sense of changing mood and setting. A small company of extraordinarily limber and graceful dancers often arrived without any particular motivation, cluttering the stage just at climactic musical moments, frequently breaking the spell. Such a device, adding pop-up texture on an otherwise bare stage, is an innovative and often successful solution. As when the dancers writhe on the stage below the singers, acting as the trolls working in the goldmines deep below the earth. And there were two dancers dressed in red suits, who appeared frequently to help guide the gods up or down the Valhalla landscape, again, annoyingly.

Another issue: The seemingly tireless tenor Stefan Vinke gave his energetic all to the enormous role of Siegfried, the hero who knows no fear, yet incessant grinning and fist-bump gestures managed to take his character out of the innocent hero category straight into clueless good ole boy territory. He did manage the arduous love duet with Brunnhilde with all the high notes intact, less so during the long last opera. When forging the sword Nothung in the third opera, his resounding “ho ho ” passages were confident and compelling. Truly a helden-tenor delivery of the booming top notes.

Hirling Bálint/Mupa

Hirling Bálint/Mupa

And another: As the Brunnhilde of the final two operas, Catherine Foster was a visual curiosity, tugging on her too-tight spandex costume and holding her arms in the awkward chicken-about-to-strike pose. Eyes always on the conductor, her voice was often glorious, but more often she failed to arrive at the top notes in crucial passages. Even less convincing was Petra Lang, who I’d seen in Bayreuth as a seductive Ortrud in Lohengrin, and as a passable Brunnhilde in Vienna. Singing the Valkure Waltraute, arriving to persuade Brunnhilde to return the ring to the Rhinemaidens and end the downward spiral of emotions and violence, Lang preened and pouted as if giving a command recital. No tender pleading, all vibrato-tainted grandstanding.

As always with the Ring, it is the orchestra—passionately led by conductor Adam Fischer—who carried the evening. The enormous horn section, the tireless precision of the strings, the celestial shimmer of six extra harps positioned three on each side of the top balconies, the Hungarian Radio Symphony Orchestra was moved firmly through the four days of music by maestro Fischer. The conductor has said that the Ring “is the kind of intense journey that cannot be interrupted.” And it wasn’t. At other venues, these four operas take place over a longer stretch of time, with a day or two break in between the long hours of performance. Here at the Müpa production it was possible to stay completely engaged each day, without a break, until Valhalla’s flames are finally quenched in the waters of the river. Surely this is one reason why several of the large roles were performed by two different singers. Two Wotans, two Brunnhildes. It was arduous and yet unforgettable to stay within the magic of the unfolding story, night after night, until the stunning end.

One musicological note. At the end of the first opera, Das Rheingold, as Wotan leads his family of handsome gods and goddesses up to their shining new Valhalla, Wagner has scored a luscious bolero. The blatantly sensuous rhythm of this procession to the home of the gods implies success, security and triumph. Such bravura makes it all the more poignant when bit by bit the immortality, composure, and fortune of the gods crumbles. It is a huge fall, underscoring the hubris of trying to have it all, and the corruption that comes with the quest for power.

Especially effective are the many passages of Sprachstimme, where for example we watch the young media manipulator Jobs working with his programmer genius partner Steve Wozniak. The two are high on their own ingenuity, the possibilities of this brave new way of communicating they are cooking up in Jobs’ family garage. This scene—one of 19 that comprise the opera—allows for a disarmingly inventive hip-hop duet by the two singers, John Moore as Jobs and tenor Bille Bruley as Woz. Its captivating energy and syncopation bookmark an apex when Apple was in its infancy, and the bloom was still on a creative partnership.

Especially effective are the many passages of Sprachstimme, where for example we watch the young media manipulator Jobs working with his programmer genius partner Steve Wozniak. The two are high on their own ingenuity, the possibilities of this brave new way of communicating they are cooking up in Jobs’ family garage. This scene—one of 19 that comprise the opera—allows for a disarmingly inventive hip-hop duet by the two singers, John Moore as Jobs and tenor Bille Bruley as Woz. Its captivating energy and syncopation bookmark an apex when Apple was in its infancy, and the bloom was still on a creative partnership.

[all photos: credit Enrico Nawrath]

[all photos: credit Enrico Nawrath] [Wotan making a guest appearance at Mime’s forge]

[Wotan making a guest appearance at Mime’s forge] [Icelandic baritone Olafur Sigurdarson as scheming Nibelung Alberich]

[Icelandic baritone Olafur Sigurdarson as scheming Nibelung Alberich]

[Wotan and the family of the gods squabbling about Valhalla]

[Wotan and the family of the gods squabbling about Valhalla] [Brunnhilde, Catherine Foster confronts Hagen, Mika Kares]

[Brunnhilde, Catherine Foster confronts Hagen, Mika Kares] [Sieglinde, Elisabeth Tiege, first meets Sigmund, tenor Klaus Florian Vogt]

[Sieglinde, Elisabeth Tiege, first meets Sigmund, tenor Klaus Florian Vogt] The device of having characters, and even actions yet to come, placed onstage simultaneously is most stunningly realized in the second act of Siegfried, where Fafner—now a feeble old man on life support—is being cared for in a luxury nursing home. Fafner is already close to death. It doesn’t take a hero to kill him. There are no heroes in Schwarz’ Ring, only ordinary mortals nursing their entitlements. At the back of the set, Alberich and Wotan sip cocktails next to each other. In the front of the set, Siegfried and Mime, fresh from the revelations in Mime’s mancave, perch on a couch with Hagen, now a teenager, dressed in the same yellow shirt and blue pants as the stolen child in the opening of das Rheingold. A young attendant, weary of feeding the aging Fafner, relaxes on the couch and begins flirting with Siegfried. The music alerts us that she is the Waldvogel who then begins to sing of Mime’s true intentions and Siegfried’s danger. The economy of storytelling by collapsing sequential time into spatial simultaneity pumps energy into an opera that can weary even diehard Wagnerites.

The device of having characters, and even actions yet to come, placed onstage simultaneously is most stunningly realized in the second act of Siegfried, where Fafner—now a feeble old man on life support—is being cared for in a luxury nursing home. Fafner is already close to death. It doesn’t take a hero to kill him. There are no heroes in Schwarz’ Ring, only ordinary mortals nursing their entitlements. At the back of the set, Alberich and Wotan sip cocktails next to each other. In the front of the set, Siegfried and Mime, fresh from the revelations in Mime’s mancave, perch on a couch with Hagen, now a teenager, dressed in the same yellow shirt and blue pants as the stolen child in the opening of das Rheingold. A young attendant, weary of feeding the aging Fafner, relaxes on the couch and begins flirting with Siegfried. The music alerts us that she is the Waldvogel who then begins to sing of Mime’s true intentions and Siegfried’s danger. The economy of storytelling by collapsing sequential time into spatial simultaneity pumps energy into an opera that can weary even diehard Wagnerites. [Siegfried, Andreas Schager discovers his love Brunnhilde]

[Siegfried, Andreas Schager discovers his love Brunnhilde] [Wotan, Polish bass/baritone Tomasz Konieczny]

[Wotan, Polish bass/baritone Tomasz Konieczny]

[Elderly Rhinemaidens attempting to seduce Siegfried]

[Elderly Rhinemaidens attempting to seduce Siegfried]

Tomasz Konieczny as Wotan: photo Nagy Attila/Müpa

Tomasz Konieczny as Wotan: photo Nagy Attila/Müpa

Nagy Attila/Müpa

Nagy Attila/Müpa Dinner each evening during the second one-hour intermission.

Dinner each evening during the second one-hour intermission. Konieczny, a true Helden-baritone is a superb actor, delivering the emotional complexity of Wagner’s vision with expressive body language and vocal nuance. The powerful voice is capable of standing up to the composer’s dense instrumentation. And he can do it for many hours across the operas. As the frustrated god ensnared by his own traps, Konieczny illuminated the eternal truth of Wotan’s passions and regrets. He appears to consider, to negotiate, to weigh the dimensions of everything he’s saying and doing. And yet the singer has performed this role dozens and dozens of times. All the irony and folly, that the gods are only as great as their worshippers, and always as small as their own addictions. comes out clearly. Master as slave.

Konieczny, a true Helden-baritone is a superb actor, delivering the emotional complexity of Wagner’s vision with expressive body language and vocal nuance. The powerful voice is capable of standing up to the composer’s dense instrumentation. And he can do it for many hours across the operas. As the frustrated god ensnared by his own traps, Konieczny illuminated the eternal truth of Wotan’s passions and regrets. He appears to consider, to negotiate, to weigh the dimensions of everything he’s saying and doing. And yet the singer has performed this role dozens and dozens of times. All the irony and folly, that the gods are only as great as their worshippers, and always as small as their own addictions. comes out clearly. Master as slave. Hirling Bálint/Mupa

Hirling Bálint/Mupa