by Christina Waters | Feb 4, 2017 | Home |

Every February 14, millions of Americans slip into a trance of ritual passion. Under its influence, we shell out serious money for extravagant and expensive perishables. Hot house roses—at $75 a dozen—will be snapped up like glue guns at an Etsy open houe. Enough chocolate bonbons to put us all into insulin overload will fly out the confectionary doors. We will put on tight clothes and really uncomfortable shoes to consume $200 dinners. Is it an extra-terrestrial virus? No, it’s Valentine’s Day, the collective heart attack that infects the very fabric of society with what optimists see as harmless indulgence.

Realists identify this spending frenzy as a clear case of social guilt, with a libidinal twist. The flowers, candy, greeting cards with icky-sweet platitudes—we use these mercantile mea culpas to atone for our butt-brained insensitivity, our inability to express our feelings. It’s payback time, with Mrs. See’s macadamia brittle as currency. Roses aren’t merely fragrant foreplay, they’re often surrogates. Instead of making a direct plea for nookie, we “say it with flowers.†Here’s the one day a year that adolescent boys (and many grownup ones) believe they’ll get lucky if they can only find the right card.

How did we get so locked into this insanity? Actually, the whole multi-billion dollar hoopla began with two ill-fated Romans—both named Valentine—who were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time, got executed and became Christian martyrs. The odyssey leading from two guys named Valentine to a modern kingdom called Hallmark has more twists than a French tickler. The two Valentines lived in 3rd century Rome as out-of-the-closet Christians. Sharing not only a name, but the same death date as well—February 14—their cult was grafted onto the very popular Lupercalia festivities held every February 15. During the pagan celebration, scantily-clad young men called Luperci would run around town, sacrificing goats, and playfully whipping women with goatskin thongs. Romans thought this behavior would increase fertility, and I have no doubt that it did.

A millennium later, having absorbed Lupercalia in the great tradition of Catholic imperialism, St. Valentine’s Day was given new sex appeal by none other than that gabby Anglo scribe, Geoffrey Chaucer, who created the very first Hallmark moment when he called Valentine’s Day a romantic “time when every fowl comes to chose his mate.†Lusty after all that Black Plague, and heady with literacy, European chivalric types began penning love poetry, which soon led to the first officially documented Valentine message, sent in 1415 by Charles, Duke of Orleans, to his wife, while he was detained in the Tower of London.

A millennium later, having absorbed Lupercalia in the great tradition of Catholic imperialism, St. Valentine’s Day was given new sex appeal by none other than that gabby Anglo scribe, Geoffrey Chaucer, who created the very first Hallmark moment when he called Valentine’s Day a romantic “time when every fowl comes to chose his mate.†Lusty after all that Black Plague, and heady with literacy, European chivalric types began penning love poetry, which soon led to the first officially documented Valentine message, sent in 1415 by Charles, Duke of Orleans, to his wife, while he was detained in the Tower of London.

Over the 16th and 17th centuries, European country folk engaged in all manner of quaint courtship rites involving herbs, rocks and secret messages on Valentine’s Day, a festival that gave them permission to express naughty intentions. And with the emergence of reliable postal services in the mid-1800s, V-Day was re-invented as an orgy of sentimental consumerism. Americans, as well as the English and the French, went mad for the new craze of sending sweet nothings through the mail. Books filled with sample Valentine’s love letters became bestsellers, and pretty soon the confectioners and florists got into the act, urging lovers to commit ever more costly acts of amorous disclosure. And they did.

In 1923 the National Confectioners’ Association took up the slogan, “Make Candy Your Valentine†echoing the avalanche of promotional hoopla that had turned Valentine’s Day into a mercantile cash cow during the Civil War era. It was a traveling salesman from Kansas City, however, who took the business of Valentine’s Day over the top when he founded his greeting card business in 1910. A workaholic with a gift for verbal reductionism, Joyce C. Hall firmly believed that modern Americans had little time to take pen in hand and compose original holiday sentiments. So he did it for them. Today the Hallmark empire he founded rakes in $6 billion each year.

In 1923 the National Confectioners’ Association took up the slogan, “Make Candy Your Valentine†echoing the avalanche of promotional hoopla that had turned Valentine’s Day into a mercantile cash cow during the Civil War era. It was a traveling salesman from Kansas City, however, who took the business of Valentine’s Day over the top when he founded his greeting card business in 1910. A workaholic with a gift for verbal reductionism, Joyce C. Hall firmly believed that modern Americans had little time to take pen in hand and compose original holiday sentiments. So he did it for them. Today the Hallmark empire he founded rakes in $6 billion each year.

How many of those special cards or bouquets of roses lead to true romance? How many chocolate truffles yield a roll in the hay? Who knows, but we’re all hopelessly hooked. How hooked? Over one billion Valentine’s cards will be sent next week. Candy sales will exceed $900 million and over 100 million roses will be purchased as preludes to romance, or at least the safest sex surrogate that money can buy.

How many of those special cards or bouquets of roses lead to true romance? How many chocolate truffles yield a roll in the hay? Who knows, but we’re all hopelessly hooked. How hooked? Over one billion Valentine’s cards will be sent next week. Candy sales will exceed $900 million and over 100 million roses will be purchased as preludes to romance, or at least the safest sex surrogate that money can buy.

by Christina Waters | Jan 28, 2017 | Art, Home |

Directed by Garth Davis and adapted from the true story “A Long Way Home,” Lion tells the fairytale saga of a young Indian boy, Saroo Brierley, who becomes lost a thousand miles away from his village, and is miraculously adopted by an Australian couple. After many harrowing misadventures as well as endearing capers, the film hands us over to the grown-up Saroo, now in college in Melbourne. Though his Australian family have been loving and supportive, Saroo increasingly burns with the need to find his Indian home, to find his mother and brother and let them know that he is alive and well.

That’s the set-up— but the film is by no stretch simply a beautifully told tale of a “lost boy” and his quest for home. Powered by urgent cinematography of chaotic Calcutta and the breathtaking coastline of Tasmania, Lion is graced with a suite of outstanding performances. Especially those of captivating young Sunny Pawar as the five-year-old Saroo, and Dev Patel as 26-year-old Saroo—but also a never-better Nicole Kidman as Saroo’s adoptive mother and Rooney Mara as Saroo’s college girlfriend.

It’s always tricky casting two strong actors as a single character, the young version and then later the character as an adult. Tricky because as we fall in love with the first version—in this case the astonishingly poised and playful Pawar—it can be wrenching to accept the character newly matured in the formidable screen presence of Patel, who is all grown up from his days stealing scenes in Slumdog Millionaire and The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. An exciting actor, the adult Patel exudes surprising sex appeal and knows how to use one of the strongest, most expressive faces in film. Caravaggio paints Shiva.

It’s always tricky casting two strong actors as a single character, the young version and then later the character as an adult. Tricky because as we fall in love with the first version—in this case the astonishingly poised and playful Pawar—it can be wrenching to accept the character newly matured in the formidable screen presence of Patel, who is all grown up from his days stealing scenes in Slumdog Millionaire and The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. An exciting actor, the adult Patel exudes surprising sex appeal and knows how to use one of the strongest, most expressive faces in film. Caravaggio paints Shiva.

Reviewers have made much of this film as a tear-jerker, destined to reduce even the most jaded viewer to jelly. Certainly it can do that. But it’s complicated. There’s a Huck Finn quality to the nightmarish odyssey of the little boy, who goes out with his brother to seek any kind of work that will help keep themselves and their mother in food. He leaves one night with the beloved older brother, and ends up at a train station where the brother tells him to stay put. Little Saroo falls asleep and when he wakes up the brother is gone and he’s completely alone at the huge railway platform. Jumping into an empty train coach, he sleeps again—such a delicious fairytale—and when he wakes the train is moving. And it keeps on moving for days, all the while carrying him farther and farther away from home. Since he’s only a child, he has no way of knowing what has happened and where he is. And so things begin to unfold.

In true Dickens fashion, some of the strangers little Saroo meets are kind and helping. Others have darker purposes. These form the heart of the first half of the film, and watching the little boy running to, and from, a variety of situations is both nerve-wracking and exciting. The utterly darling Pawar has us in the palm of his hand and then his life suddenly blooms with the love and care of his new parents a world away.

Nicole Kidman knocked me out in all of her scenes, but the one in which she explains to the grown-up Saroo just why she wanted to adopt him will destroy you. Even as Virginia Woolf in The Hours she was never this present, this entirely focused upon a single idea as she is here. (There’s also a second adopted Indian brother who has “issues,” and even in a fairytale the path to maturity never runs smoothly.)

Nicole Kidman knocked me out in all of her scenes, but the one in which she explains to the grown-up Saroo just why she wanted to adopt him will destroy you. Even as Virginia Woolf in The Hours she was never this present, this entirely focused upon a single idea as she is here. (There’s also a second adopted Indian brother who has “issues,” and even in a fairytale the path to maturity never runs smoothly.)

Once Saroo/Patel begins his Google-enhanced quest to pinpoint where he might have gotten on the train all those years ago, and struggles to locate his home village, the film gains intensity. Of course we want to see how he will find his home, whether his family still lives, and we can taste the reunion he so needs. But somewhere in there a generic ending starts to form itself. Not every stitch ends up in a neat crochet, a few corners of credibility are cut, and yet. And yet. The resolution of the quest is as satisfying as any epic tale can get.

The film was loaded with highest quality everything. Story, cinematography, acting, music, direction—I left feeling better than I had when I arrived. Lion delivered everything a movie should. And I loved it.

(Only one of those obligatory “true story” film endings, where they show footage of the real people upon whose lives the film is based, threatened to destroy the spectacular saga we’d just seen. Note to directors: don’t do this. Resist the cornball desire to show us “the way they are today.” Just don’t do it.]

by Christina Waters | Jan 28, 2017 | Art, Home |

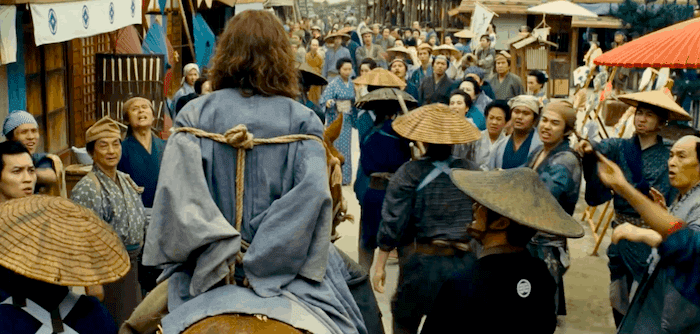

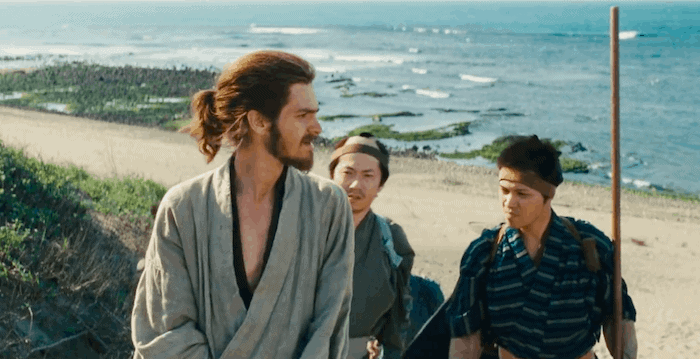

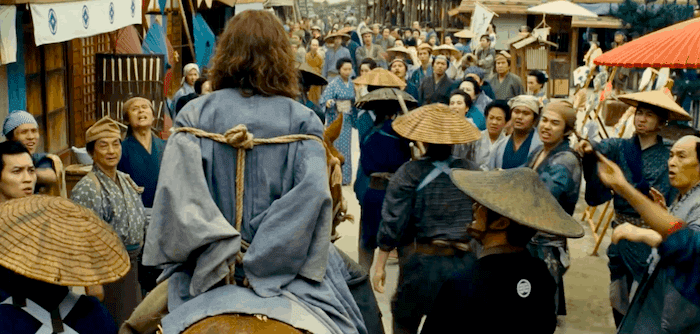

You can take the boy out of the Church, but you can’t take the Church out of Marty Scorsese. Fearless and probing, director Scorsese seems unstoppable in his restless (tormented?) quest for redemption. There have been other paths through his personal journey that circles around the miracle of the Christian resurrection. Good Fellas. The Wolf of Wall Street. The Last Temptation of Christ. But Silence is the most intimate, even in its monumental scale. Almost shocking in its adherence to religious ritual, prayer, ecclesiastical devotion, Silence portrays as much as it narrates an historic moment of brutal religious persecution—of Portuguese Jesuit missionaries by the dominant political structure of Japan, to whose shores the priests have come to convert poor peasants to the One True Faith.

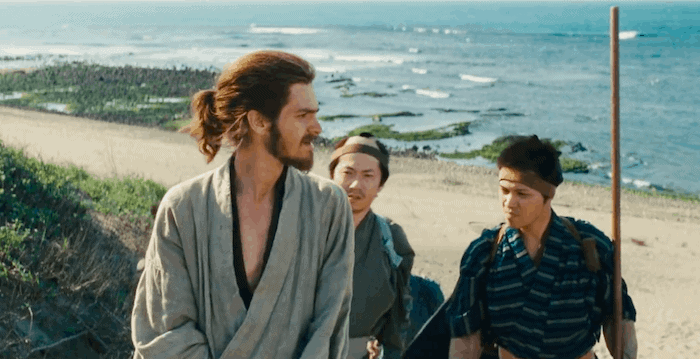

Andrew Garfield as Father Rodrigues and Adam Driver as Fr. Garrpe play 17th century priests on a quest to find their mentor and teacher Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson), rumored to have renounced his faith (apostasy, in Catholic terms) and not heard from in years. Such a quest—for a lost man of God, by two young and untried ministers—takes a resourceful storyteller through rich emotional and scenic landscapes. And Silence is stuptifyingly beautiful. Imagine an Ingmar Bergman meditation on lost faith and inner psychology, set in the atmospheric texture of Japan’s lakes, shores, volcanic terrain, and design-intensive interiors. It is gorgeous, gorgeous enough to take the Oscar for Best Cinematography, to be sure. Yet the healing benediction the director so desires—like the elusive and silent God he seeks— remains just off-screen.

Andrew Garfield as Father Rodrigues and Adam Driver as Fr. Garrpe play 17th century priests on a quest to find their mentor and teacher Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson), rumored to have renounced his faith (apostasy, in Catholic terms) and not heard from in years. Such a quest—for a lost man of God, by two young and untried ministers—takes a resourceful storyteller through rich emotional and scenic landscapes. And Silence is stuptifyingly beautiful. Imagine an Ingmar Bergman meditation on lost faith and inner psychology, set in the atmospheric texture of Japan’s lakes, shores, volcanic terrain, and design-intensive interiors. It is gorgeous, gorgeous enough to take the Oscar for Best Cinematography, to be sure. Yet the healing benediction the director so desires—like the elusive and silent God he seeks— remains just off-screen.

[I’ll get back to my main commentary in a minute, but let me digress. Never has an audience been dragged through the spectacle of so much mud, so much rain, so many bad hair days, so many painfully skinny bodies, and such brutally thick accents as in Silence. So closely does Scorsese’s loveletter adhere to the faith he can’t quite abandon that you can practically walk the Stations of the Cross in the 2 hours + of the film. Frankly, I admire all of that, the willingness to set irony aside and devoutly detail the deep tissue message of Christian martyrdom, the charity extended to one’s enemies, the absolution granted even to serial liars and thieves. But can we talk about casting?

Scorsese insisted on casting fine Japanese actors in the appropriate roles. Alas, during much of the film these same actors speak their lines in English. Incomprehensible English. This was surely the time for subtitles Marty! The main protagonist, the priest upon whose skinny shoulders the tale hangs is played by puppy-dog visaged Andrew Garfield. He acts his guts out and is incredibly convincing as a priest pushed to the very gates of hell, but his face is so weak that the film caves in during his extended scenes of captivity and philosophical dialogue with Buddhist honchos. He is seriously unappealing. (See my review of Lion, where we would follow the compelling Dev Patel anywhere. I would follow the chinless Garfield nowhere. Perhaps this is simply a matter of taste, but I doubt it.)

The most egregious casting woe is, in two words, Liam Neesom. As the apostate priest/mentor, finally discovered in an upscale domicile of Buddhist temple elite, Neeson looks as much like a Porteguese friar as do I, the product of Norwegian/Scottish-Irish ancestors. Give me a break. Plus his sorrow-ravaged face appears to be permanently dialed to “agony.”

The most egregious casting woe is, in two words, Liam Neesom. As the apostate priest/mentor, finally discovered in an upscale domicile of Buddhist temple elite, Neeson looks as much like a Porteguese friar as do I, the product of Norwegian/Scottish-Irish ancestors. Give me a break. Plus his sorrow-ravaged face appears to be permanently dialed to “agony.”

We, the audience, want to love everything that Martin Scorsese does. We endure beheadings, torture by water, by fire, by mud. We endure the sight of Adam Driver’s ribcase and Andrew Garfield’s chipmonk cheeks. But it’s hard to endure Liam Neeson’s massive Irish frame and face pretending to look Portuguese. Where was Antony Banderas when this film was cast? I know he can’t act but he sure can look authentically Portuguese.

Okay. Here’s my summary. Silence was as elegaic a film as it is possible to make. The music alone was transcendent. It was terrific to hear so much of the Catholic mass actually said in Latin (devotees of old school Catholicism will be thrilled), and I found my eyes deeply comforted by the impeccable design of Japanese interiors. The ocean never looked better. But I couldn’t recommend this film with any enthusiasm. Cinematographic geeks definitely will want to check it out. Everybody else, probably not. I would recommend streaming Scorsese’s actual religious masterpiece, The Last Temptation of Christ, and feasting on what sensual apostasy can look like when it’s done with religious fervor. And by Willem Dafoe.

by Christina Waters | Jan 21, 2017 | Home |

Watching Scarlett Johansson speak at the Women’s March on Washington I found myself thinking and feeling many things. Maybe that short, Joan-of-Arc-ish haircut will inspire lots of young women my students’ age to get rid of their long stringy fashion locks, I mused. Cut their hair, stop obsessing about hipster attire and get down to business. Miles to go yet, ladies. Miles to go.

Lots of things ran and pulsed through my mind as I watched the thick flow of excitement fill the streets and boulevards of the city where I spent four years as an undergraduate. All those monumental intersecting avenues, the marble public buildings, museums, and institutes. The halls of power looking strangely impotent and silent, surrounded by girl power, baby boomer indignation, woman—and men too—pushed too far. Deciding that here was the line in the sand and they would determine just exactly where it should be placed, and how it could not, or could not be moved.

As I watched—ashamed that I hadn’t gotten on a plane myself and joined the physical manifestation of years, decades, generations of neglect, exploitation, invisibility, abuse, inequality, and just plain exclusion from the dominant boy’s club of white, capitalist, bureaucratic entitlement—as I watched I loved the sheer variety (I know “diversity” is the reigning term, but “variety” is freer of political rhetoric) of marching costumes, of hand-painted, hand-lettered signs and banners. Tears in my eyes, absolutely. But then I began to focus on what seemed so obvious, and important, that it almost escaped notice.

As I watched—ashamed that I hadn’t gotten on a plane myself and joined the physical manifestation of years, decades, generations of neglect, exploitation, invisibility, abuse, inequality, and just plain exclusion from the dominant boy’s club of white, capitalist, bureaucratic entitlement—as I watched I loved the sheer variety (I know “diversity” is the reigning term, but “variety” is freer of political rhetoric) of marching costumes, of hand-painted, hand-lettered signs and banners. Tears in my eyes, absolutely. But then I began to focus on what seemed so obvious, and important, that it almost escaped notice.

All those pink pussyhats. “My mother knitted this for me to wear,” was a repeated theme of interviews I watched. Now we all know just how ancient a handcraft is knitting. Archetypal women’s craft. Knitting. Women have been knitting hats to warm the heads of those they love for centuries. And here we had a sea of pink knitted hats. Hats worn by marchers who had turned off Facebook, left the digital playing field behind, and traveled in their real world physical bodies to be together with other bodies, in real time and real space, moving together down a boulevard of dreams. These were not promotional hats cranked out by professional organizers. These were grass-roots hand-made hats, thus legitimizing this uncanny phenomenon as genuinely grass-roots driven. [More about those hats here.]

This was no digital exercise I saw. It was a sudden pop-up of the hand arts decorating human bodies moving through the streets on a cold January day in the 21st century.

I was stunned and gratified. Being present, showing up for the cause of defying the status quo, in hand-made paraphernalia. Here was a future I could celebrate! [photo:nbc news]

I was stunned and gratified. Being present, showing up for the cause of defying the status quo, in hand-made paraphernalia. Here was a future I could celebrate! [photo:nbc news]

As much as any of the important, emotional, and hopefully transformational conversation that took place that day, was this re-claiming of the non-digital. Here were women moving beyond the self-congratulatory safety of FB, beyond the obsession of texting, and going way out of their physical comfort zones into the cold, with millions of sister/strangers —also wearing those hand-crafted pink agit-hats—and all I could do was hope that I would see it happen again. Soon. Often. Always.

Power to the body! the Vox Populi and its knitted pink cap!

[photo, top: business insider]

by Christina Waters | Jan 16, 2017 | Home |

Those squeamish viewers who found Manchester by the Sea difficult to watch will find Paul Verhoeven’s new film, Elle, way too much to handle. Refreshingly non-formulaic (i.e. non Hollywood), the film stars a stunning Isabelle Huppert as a successful Parisian, Michele LeBlanc, whose animated fantasy film company specializes in erotic violence. The film opens with a voyeur’s view of her rape, and ends, well, with a whole lot more. Huppert once again shows—as she did in The Piano Teacher—that she can, and will, do anything required by the sort of 100% adult cinema in which European filmmakers specialize. Oscar please!

So eccentric, provocative, satirical, and violent is Elle that I find it difficult to be sure of any one aspect of it. In other words, it’s hard to say what I saw and how I can interpret a film that lacerates all the genres it vivaciously defies. A black comedy of bourgeois manners, Elle skewers French elegance and 21st century family dysfunction, takes aim at infidelity—something our protagonist Michele LeBlanc indulges when it strikes her fancy—and exposes the fraudulence in most conventional relationships, with one or two exceptions.

Back-tracking every now and then to reveal more and more important yet incomprehensible bits of Michele’s past, Elle‘s heart is bloodied by the horrific incident involving her father back when Huppert’s character was a young girl. Haunted, yet defiant about this past, Michele coolly ignores her friend’s urgings to tell the police about her recent violent rape. Instead she decides to get even.

Back-tracking every now and then to reveal more and more important yet incomprehensible bits of Michele’s past, Elle‘s heart is bloodied by the horrific incident involving her father back when Huppert’s character was a young girl. Haunted, yet defiant about this past, Michele coolly ignores her friend’s urgings to tell the police about her recent violent rape. Instead she decides to get even.

But Michele LeBlanc is no Charles Bronson on a systematic binge of revenge, and in fact her relationship with her rapist turns out to be as unnerving as every other other one in her life. With her failed novelist ex-husband, her best friend (whose husband is Michele’s current lover), her son and his spoiled abusive girlfriend, and the handsome neighbor with whom she has unexpectedly dangerous liaisons. This film is so unpredictable, so laser focused that you have to be willing to fling yourself into the action and simply have faith that the magnificent Huppert will take you somewhere both unexpected and somehow redemptive. (Or whatever the post-truth version of redemptive might be.) She does both, and much more. It’s often tough to watch, and just as often potently funny. (Six people walked out of the theater after the first ten minutes.)

No cow is too sacred to be slapped around by Verhoeven and his lead actor. Huppert’s face is a landscape of human disappointment, cleverness, longing, and impatience. Mercurial as a skyful of hurricane clouds, she drives almost every moment of the film, forcing us to love, loathe, and champion her intelligence and her guts. Few actors have ever been put through so much raw physical ordeal—and all of it clothed in layers of emotional inquiry. The pursing of lips, a raised eyebrow, a clenched fist. The suddenly raised eyes.She is a galaxy of human-all-too-human gestures and cynical insights. Not a Disney film. What a ride!

A millennium later, having absorbed Lupercalia in the great tradition of Catholic imperialism, St. Valentine’s Day was given new sex appeal by none other than that gabby Anglo scribe, Geoffrey Chaucer, who created the very first Hallmark moment when he called Valentine’s Day a romantic “time when every fowl comes to chose his mate.†Lusty after all that Black Plague, and heady with literacy, European chivalric types began penning love poetry, which soon led to the first officially documented Valentine message, sent in 1415 by Charles, Duke of Orleans, to his wife, while he was detained in the Tower of London.

A millennium later, having absorbed Lupercalia in the great tradition of Catholic imperialism, St. Valentine’s Day was given new sex appeal by none other than that gabby Anglo scribe, Geoffrey Chaucer, who created the very first Hallmark moment when he called Valentine’s Day a romantic “time when every fowl comes to chose his mate.†Lusty after all that Black Plague, and heady with literacy, European chivalric types began penning love poetry, which soon led to the first officially documented Valentine message, sent in 1415 by Charles, Duke of Orleans, to his wife, while he was detained in the Tower of London. In 1923 the National Confectioners’ Association took up the slogan, “Make Candy Your Valentine†echoing the avalanche of promotional hoopla that had turned Valentine’s Day into a mercantile cash cow during the Civil War era. It was a traveling salesman from Kansas City, however, who took the business of Valentine’s Day over the top when he founded his greeting card business in 1910. A workaholic with a gift for verbal reductionism, Joyce C. Hall firmly believed that modern Americans had little time to take pen in hand and compose original holiday sentiments. So he did it for them. Today the Hallmark empire he founded rakes in $6 billion each year.

In 1923 the National Confectioners’ Association took up the slogan, “Make Candy Your Valentine†echoing the avalanche of promotional hoopla that had turned Valentine’s Day into a mercantile cash cow during the Civil War era. It was a traveling salesman from Kansas City, however, who took the business of Valentine’s Day over the top when he founded his greeting card business in 1910. A workaholic with a gift for verbal reductionism, Joyce C. Hall firmly believed that modern Americans had little time to take pen in hand and compose original holiday sentiments. So he did it for them. Today the Hallmark empire he founded rakes in $6 billion each year. How many of those special cards or bouquets of roses lead to true romance? How many chocolate truffles yield a roll in the hay? Who knows, but we’re all hopelessly hooked. How hooked? Over one billion Valentine’s cards will be sent next week. Candy sales will exceed $900 million and over 100 million roses will be purchased as preludes to romance, or at least the safest sex surrogate that money can buy.

How many of those special cards or bouquets of roses lead to true romance? How many chocolate truffles yield a roll in the hay? Who knows, but we’re all hopelessly hooked. How hooked? Over one billion Valentine’s cards will be sent next week. Candy sales will exceed $900 million and over 100 million roses will be purchased as preludes to romance, or at least the safest sex surrogate that money can buy.

It’s always tricky casting two strong actors as a single character, the young version and then later the character as an adult. Tricky because as we fall in love with the first version—in this case the astonishingly poised and playful Pawar—it can be wrenching to accept the character newly matured in the formidable screen presence of Patel, who is all grown up from his days stealing scenes in Slumdog Millionaire and The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. An exciting actor, the adult Patel exudes surprising sex appeal and knows how to use one of the strongest, most expressive faces in film. Caravaggio paints Shiva.

It’s always tricky casting two strong actors as a single character, the young version and then later the character as an adult. Tricky because as we fall in love with the first version—in this case the astonishingly poised and playful Pawar—it can be wrenching to accept the character newly matured in the formidable screen presence of Patel, who is all grown up from his days stealing scenes in Slumdog Millionaire and The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. An exciting actor, the adult Patel exudes surprising sex appeal and knows how to use one of the strongest, most expressive faces in film. Caravaggio paints Shiva. Nicole Kidman knocked me out in all of her scenes, but the one in which she explains to the grown-up Saroo just why she wanted to adopt him will destroy you. Even as Virginia Woolf in The Hours she was never this present, this entirely focused upon a single idea as she is here. (There’s also a second adopted Indian brother who has “issues,” and even in a fairytale the path to maturity never runs smoothly.)

Nicole Kidman knocked me out in all of her scenes, but the one in which she explains to the grown-up Saroo just why she wanted to adopt him will destroy you. Even as Virginia Woolf in The Hours she was never this present, this entirely focused upon a single idea as she is here. (There’s also a second adopted Indian brother who has “issues,” and even in a fairytale the path to maturity never runs smoothly.)

Andrew Garfield as Father Rodrigues and Adam Driver as Fr. Garrpe play 17th century priests on a quest to find their mentor and teacher Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson), rumored to have renounced his faith (apostasy, in Catholic terms) and not heard from in years. Such a quest—for a lost man of God, by two young and untried ministers—takes a resourceful storyteller through rich emotional and scenic landscapes. And Silence is stuptifyingly beautiful. Imagine an Ingmar Bergman meditation on lost faith and inner psychology, set in the atmospheric texture of Japan’s lakes, shores, volcanic terrain, and design-intensive interiors. It is gorgeous, gorgeous enough to take the Oscar for Best Cinematography, to be sure. Yet the healing benediction the director so desires—like the elusive and silent God he seeks— remains just off-screen.

Andrew Garfield as Father Rodrigues and Adam Driver as Fr. Garrpe play 17th century priests on a quest to find their mentor and teacher Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson), rumored to have renounced his faith (apostasy, in Catholic terms) and not heard from in years. Such a quest—for a lost man of God, by two young and untried ministers—takes a resourceful storyteller through rich emotional and scenic landscapes. And Silence is stuptifyingly beautiful. Imagine an Ingmar Bergman meditation on lost faith and inner psychology, set in the atmospheric texture of Japan’s lakes, shores, volcanic terrain, and design-intensive interiors. It is gorgeous, gorgeous enough to take the Oscar for Best Cinematography, to be sure. Yet the healing benediction the director so desires—like the elusive and silent God he seeks— remains just off-screen. The most egregious casting woe is, in two words, Liam Neesom. As the apostate priest/mentor, finally discovered in an upscale domicile of Buddhist temple elite, Neeson looks as much like a Porteguese friar as do I, the product of Norwegian/Scottish-Irish ancestors. Give me a break. Plus his sorrow-ravaged face appears to be permanently dialed to “agony.”

The most egregious casting woe is, in two words, Liam Neesom. As the apostate priest/mentor, finally discovered in an upscale domicile of Buddhist temple elite, Neeson looks as much like a Porteguese friar as do I, the product of Norwegian/Scottish-Irish ancestors. Give me a break. Plus his sorrow-ravaged face appears to be permanently dialed to “agony.”

As I watched—ashamed that I hadn’t gotten on a plane myself and joined the physical manifestation of years, decades, generations of neglect, exploitation, invisibility, abuse, inequality, and just plain exclusion from the dominant boy’s club of white, capitalist, bureaucratic entitlement—as I watched I loved the sheer variety (I know “diversity” is the reigning term, but “variety” is freer of political rhetoric) of marching costumes, of hand-painted, hand-lettered signs and banners. Tears in my eyes, absolutely. But then I began to focus on what seemed so obvious, and important, that it almost escaped notice.

As I watched—ashamed that I hadn’t gotten on a plane myself and joined the physical manifestation of years, decades, generations of neglect, exploitation, invisibility, abuse, inequality, and just plain exclusion from the dominant boy’s club of white, capitalist, bureaucratic entitlement—as I watched I loved the sheer variety (I know “diversity” is the reigning term, but “variety” is freer of political rhetoric) of marching costumes, of hand-painted, hand-lettered signs and banners. Tears in my eyes, absolutely. But then I began to focus on what seemed so obvious, and important, that it almost escaped notice. I was stunned and gratified. Being present, showing up for the cause of defying the status quo, in hand-made paraphernalia. Here was a future I could celebrate! [photo:nbc news]

I was stunned and gratified. Being present, showing up for the cause of defying the status quo, in hand-made paraphernalia. Here was a future I could celebrate! [photo:nbc news]

Back-tracking every now and then to reveal more and more important yet incomprehensible bits of Michele’s past, Elle‘s heart is bloodied by the horrific incident involving her father back when Huppert’s character was a young girl. Haunted, yet defiant about this past, Michele coolly ignores her friend’s urgings to tell the police about her recent violent rape. Instead she decides to get even.

Back-tracking every now and then to reveal more and more important yet incomprehensible bits of Michele’s past, Elle‘s heart is bloodied by the horrific incident involving her father back when Huppert’s character was a young girl. Haunted, yet defiant about this past, Michele coolly ignores her friend’s urgings to tell the police about her recent violent rape. Instead she decides to get even.