by Christina Waters | Nov 13, 2021 | Book |

Last Call: Poems by Stephen Kessler

Essayist, translator, pundit, and poet Stephen Kessler has been courting the muses for over 50 years. In his latest, largest, and 12th collection of poems, Last Call, Kessler’s elegant technique explores Santa Cruz, music, lost love, aging, irony, and pandemic epiphanies.

Q: Briefly tell me about how this collection of poems came about. What time period did they span? Where do they fit in your oeuvre?

My books tend to coincide with periods or “chapters” in my life. The poems in Last Call were written between January 2017, when I turned 70, and February of this year, when I received my first Covid vaccination. Those years happened to coincide with two terrible events in the personal and the public realm: the breakup of my marriage and the presidency of Donald Trump. So there was a lot of tough material to process, which accounts for the sense of grief and loss, especially in the first section of the book. “Bad Luck Charms.” My hope was and is through the alchemy of the language to turn all that hurt into something else—including ironic distance—the same way singing the blues can transform pain and heartbreak into something beautiful and consoling, maybe even funny.

Q: You’re known for the jazz syncopation of your poems, the way the lines stride and swing into each other. Do you read the work aloud as you write? or only afterward? How does it work?

I write by hand on paper (or with occasional exceptions on a manual typewriter) and try to let my hand do the thinking guided by the technical skills I’ve developed over about 65 years of practice, just as a jazz musician typically improvises spontaneously without reflection, letting the trained ear and fingers direct where the melody is going. I hear it in my head as it’s being written and try to just let it rip according to where the sounds of the language lead. Then I may read it to myself in a whisper to feel how it tastes as much as to hear how it sounds. If it feels more or less like natural speech but spring-loaded for torque from one line to the next, that’s the effect I’m hoping for. Sometimes it comes out right the first time and at other times it requires revision. But I always let it sit for a while to let it cool off so I can have a more objective look—and listen—at what I’ve written. If it’s not working, and I can’t fix it with a few adjustments, I tend to set it aside and move on to the next one, rather than try to save every poem by revising as extensively as I did when I was younger.

Q: I see more willingness to indulge in alliterative lines, in internal rhymes within the lines themselves. Were you consciously expanding your style in this collection?

Alliteration, internal rhyme, vowel rhyme and other prosodic devices have always served as my tools and techniques of composition, so I don’t see how this book is any different in that respect from most of my earlier work. But one’s style evolves, and I enjoy surprising myself from one line, one poem, and certainly one book to the next. At this stage of the game, I’m less concerned with writing a perfect poem (or a perfect book) than in letting the lines move to their own measure, so in that respect they may feel more indulgent or expansive in some way. But as I said, I’ve been reading and writing verse for so long—since childhood—that I feel enough confidence in my technical chops to let the poem take its own organic form. So there are lots of different shapes and sizes and styles of poems in this collection.

Q: Which muse pulled stronger, growing older or enduring quarantine?

Normally I’m accustomed to spending a lot of time at home alone with the writing, so the lockdowns weren’t all that inconvenient for me. But being increasingly old is something I don’t know if anyone ever gets used to, so the physical and psychic realities of entering “old age” (even though 70 is the new 50, and I’m reasonably healthy) play a much bigger part in the composition of this book—only the last year of which, maybe a dozen or 15 poems, was written during the pandemic.

Q: Can you reflect on the bittersweet irony of publishing your most ambitious late-career book, and calling it Last Call just when COVID shut down the world? As if the title were the leitmotif of the era itself.

The title came to me very early on, with the poem of that title, which I think was written about four years ago, so the pandemic had nothing to do with it. That poem was literally written at the bar of a local restaurant where the bartender was calling for any last orders before closing. It matched my gloomy mood of the moment and seemed fitting for the late-life themes I was wrestling with. Everyone asks if it’s meant as a valediction, and I think probably not, but then again, you never know. I certainly intend to keep writing, but that’s not entirely up to me. I expect the world will go on, with or without me.

Q: Much as complex recipes in fine cuisine, this work more than ever lays down opposing riffs—sweet and salty, joy and pain, darkness and clarity. A poet’s-eye view of the rhythm of existence itself?

In writing, as in cooking, I use whatever ingredients and seasonings are at hand. I definitely prefer a book—my own or anyone else’s—that moves through a range of themes and moods and motifs rather than repeats a formula over and over. Doesn’t everyone go through different rhythms of existence? Looking back over some 50 years of publishing, I feel as if I’ve consistently tried to respond as honestly as possible to the full range of my lived experience. I just hope I’ve gone deep enough that the poems resonate with the experience of others.

Q: You never draw attention to craft—form, composition, conscious/slant rhyming—in your work. Yet I have to admire the impeccable line breaks like some of these in “Last Call”:

trees crashing through

roofs, blackouts,

rivers rising and

spilling into living

rooms leaving a film

Does the spontaneous observation trump craft in your work? Or were these poems different in feel/form?

What you call “craft” I call technique, and it’s baked into the writing in a way that’s inseparable from imagination or observation, just as form and content in the best poems are seamlessly integrated. I learned the fundamentals when I was in elementary school by reading (for fun!) traditional English poetry (my family had a paperback copy of Palgrave’s Golden Treasury of Songs and Lyrical Poems) and writing imitations of rhymed and metered verse—usually just to entertain my friends. I wrote the lyrics to the class song for both grade school and high school graduations. I learned to write a poem for any occasion. Most of those efforts, when they weren’t intentionally funny, were no good as poetry except in a formal sense: they scanned metrically according to whatever form I was imitating, and they rhymed at the ends of the lines. So listening for rhythm and rhyme became habitual, and by the time, around 18 or 19, I started writing “free verse”—a misnomer because it demands even more formal control than fixed forms, requires that you create your own form on the blank page—these prosodic principles were ingrained in me. It took me many more years, decades even, to learn to deploy them effectively in composition, but by now I’ve been doing it for so long that the form the poem takes is second nature, and almost unconscious until I look and see what I’ve done. In the case of the title poem you quote from, the length of the lines was determined by the width of the notebook page I was writing on; the breaks just happened to work as written, so I didn’t mess with it. Other poems written in the same pocket notebook came out completely differently because I heard the breaks to fall in different places.

Q: Some poems in this collection are only a few words wide, forcing me to read downward (vertically) in a single gulp. Others stretch more words across the page, slowing down your voice and the reader’s intake. How do these decisions come to you?Funny, for me, short lines tend to slow a poem down, and long lines move more swiftly across the page. That just shows how we all read differently. As noted above, in some cases it’s the width of the page I’m writing on, or in the case of “Borges’s Belt,” it was the strip of paper I was typing on as the poem describes its own physical creation. “Paisley Yours” is in the voice of the model in the middle of a magazine page, and the narrow white space on either side of the image determined the long skinny shape of the poem as I typed it on my 1974 Adler manual portable. Others may start as prose in the first draft and once I see the whole thing I find where the breaks belong. And still others are composed originally as verse because the lines come to me one at a time and that’s the way I set them down. Most of these decisions make themselves according to how the composition unfolds. I don’t have any rational method, it’s a much more intuitive process based on the measure I hear in my head. I find the formal openness yet technical precision required of “free verse” to be as mysterious and unpredictable as how the poem’s images are imagined—usually by sonic association more than conscious choice. At best I feel like a medium, or an amanuensis to the muses, just taking dictation.

Q:Do you know when the words are good?

Usually—but not how. Sometimes in real time as they’re set down; at other times only later, from a more detached perspective. In some ways it’s easier to know when they’re not so good, when they’re clunky or prosaic or just “off” in some way. When the good ones are coming I’m too caught in the flow to really understand what’s happening, and when I see what I’ve done I can’t figure out how it happened. Composition as possession. I’ve learned to surrender to whatever it is that’s got hold of me, usually some kind of rhythmic riff, a few words strung together, a phrase unfolding according to its own melodic logic. And it feels good when the words are good—so I guess that’s how I know.

Q: Finally, an appreciation. “Discourse on Distraction” is a disarming piece of rumination, in which you move from the almost Platonic general down to the tangible specific. The last lines are among your finest, in which you clearly speak to the man within the poet:

there is no escaping the script you write with every step,

the strange rhymes ringing amid the dissonance,

the gifts, the great griefs,

the peripheral visions.

___________________________

Last Call, poems by Stephen Kessler

Black Widow Press, 200 pages, $19.95

Interview by Christina Waters

Zoom Forward reading Friday November 19, 5pm (Pacific time)

Northern Lights: Images from Per Forsström

by Christina Waters | Jul 28, 2020 | Home |

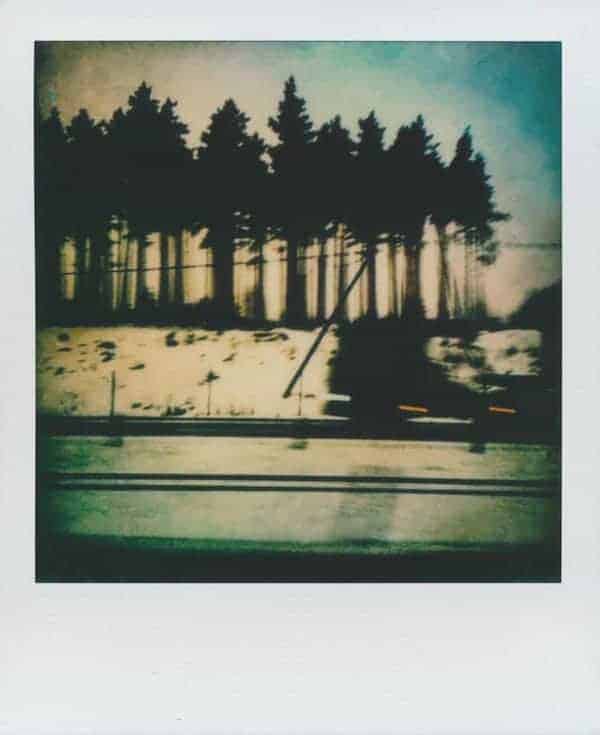

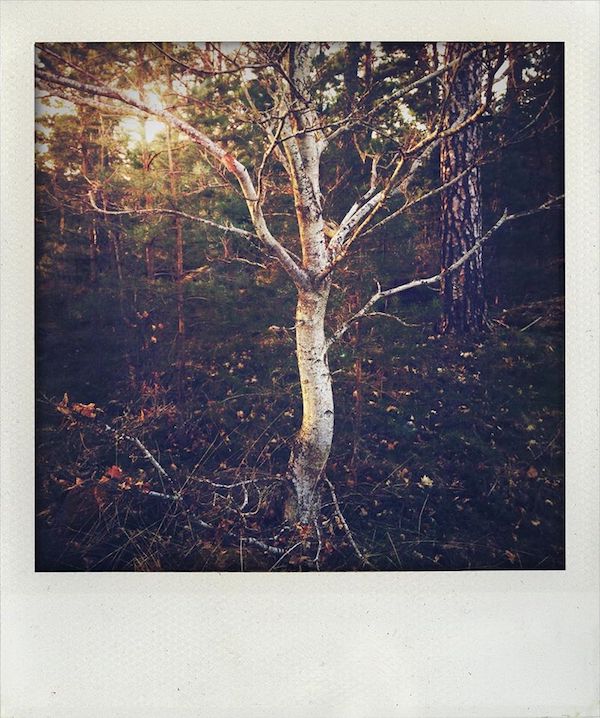

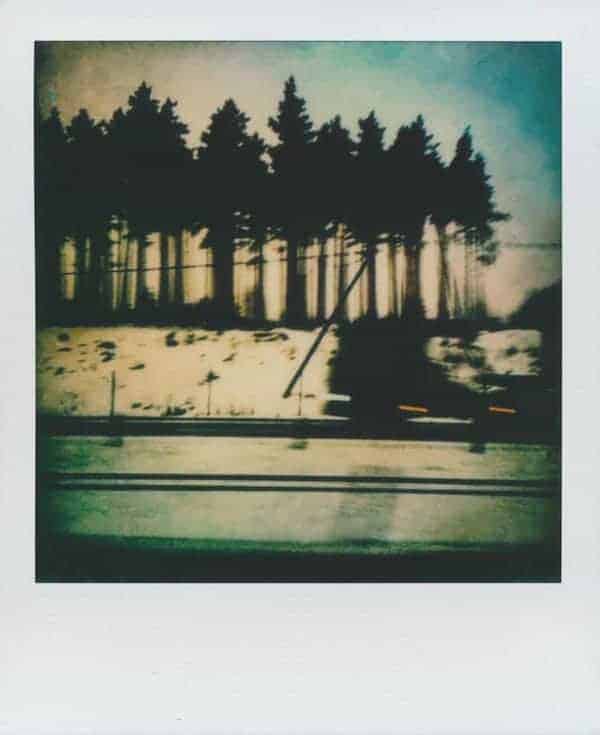

If Edvard Munch had been a photographer he might have been Per Forsström, a Stockholm-based new wave polaroid photographer whose growing oeuvre evokes the ambiguity of dreams. And like dreams, Forsström’s work is filled with seductive alliances between his skilled eye, Fate, and the richness of the unconscious.

I first saw his work on social media and was instantly hooked on the shimmering light and edginess of memory they seem to contain. The photographs are haunting. Often it’s the framing, the unexpected angles and sensitive composition. Most of these images are bathed in the soft focus and blurred margins of remembered summer afternoons. Certainly the artist’s manipulation of the famously viscous surface of Polaroid emulsion lends his work a fairytale quality. Reality that knows more than we realize.

Yet these are not pretty photographs in any clichéd sense. They are energized as much by the nordic noir of Henning Mankell and Jo Nesbo as they are by the midnight coves of Ingmar Bergman. I immediately felt a bond between the eternal regrets of Bergman’s finest films, Wild Strawberries for example, and the lonely forests Forsström clearly knows so well.

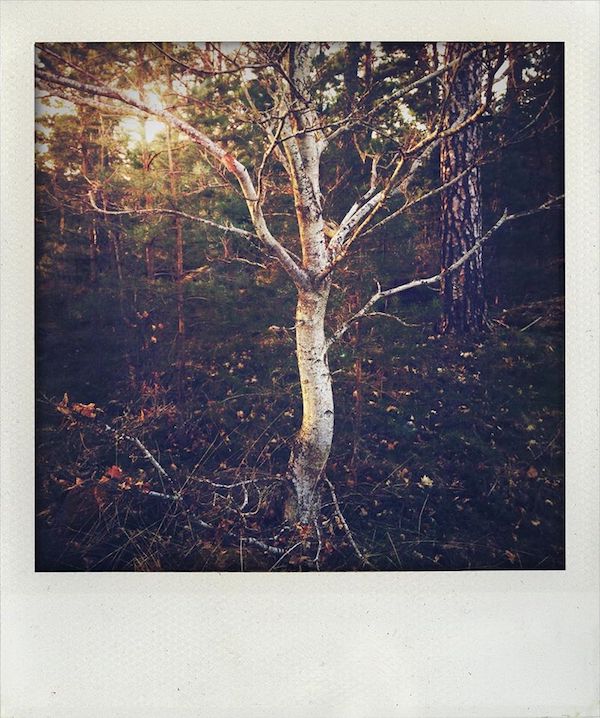

An art teacher in Stockholm, baby boomer Forsström grew up in the old Swedish university town of Lund. He drew, painted, dreamed of being a comic book artist, studied art in the University, and soon became a father. Carpentry, archaeology, taxi driving, he sampled many professions before settling in Stockholm to teach art. In 2013 he bought a camera, a Polaroid 360 with an electronic flash and “became obsessed.” Then he discovered the Impossible Project, an alliance of polaroid devotées with whom he shared a passion for experimental images. “I’m not at all interested in perfection technically speaking. That bores me to death.”

Which is why, in addition to polaroids and the refinements of an old school Hasselblad camera, Forsström works with the fixed focus challenges of the plastic Holga and Diana cameras.

“I just happened to see this beautiful young oak tree as I was walking in the woods at the golden hour. It was something very gracious about it and I wanted to capture this tactile, dreamy almost unearthly graciousness.”

The beach scenes he captures reminded me of the place where I live, on the ocean, albeit one very distant from the Baltic Sea of Forsström’s images. On the beach—his beach, my beach, any beach— we revisit our childhoods, those summer holidays in which we could escape growing up. Where we remained forever young. Carefree, if we were lucky.

“To me the sandy beaches in the south of Sweden are almost unreal in the warm sunny summer days, long stretches of white sand, the stillness, the cold clear water, yes it’s dreamlike. Also the feeling of the blinding sunlight reflected in the water and the white sands, trying to evoke a feeling of all that, a drowsiness. Memories, yes, and you are helpless to them.”

Such a rich and surprising picture. This one felt like a Baroque image, or perhaps a quiet moment in the studio of Velasquez, while he was painting Las Meninas. The smoky chiaroscuro seems to transcend the medium and displays the photographer’s visual instincts, combined with a variety of avant garde printing techniques. So deep are the darkest tones that we feel we can enter the picture plane and inhabit its various secrets and perfumes.

Forsström recalls making this photograph. “This self portrait comes from my love of Caravaggio and the chiaroscuro and of course Rembrandt. I shot this with a Hasselblad 501CM in bulb mode, experimenting with time and movement. I used no flash. I always try to have elements of uncertainty, a kind of disturbing nerve because that’s how I relate to the world.”

Forsström’s most seductive images take a few moments to become recognizable. Some, such as this mysterious faintly tinted picture, never quite reach resolution—much as a darkroom image might elude full disclosure.

But that’s their magic. They defy easy explanation. This one, with its soft focus edges and uncertain subject matter seems to lie just off shore. We can almost pull them in and make sense of them, but not quite. Like the most delicious and maddening dreams, they defy our grasp. And that is their power.

“The church in snow, it’s funny, I was just by chance driving past it. It had this magnetic aura, very old, Täby kyrka built in the 13th century. Inside there’s this famous wall painting by Albertus Pictor where Death plays chess with a poor mortal. This is the painting that inspired Ingmar Bergman in The Seventh Seal.”

This final image, a manipulated and distressed self-portrait, contains all the poetry of Forsström’s best pictures to date.

We see the artist, looking back at us, through many layers of dreams? years? memories? Like Alice, he seems to have slipped through the looking glass and now exists within mysteries beyond language. Only the puzzling textures suggest what he has seen. One suspects that the person we see through these layers of ink and chemicals is suspended in another world. Another time.

Per Forsström‘s photographs allow him the luxury of this rare and playful time travel. Perhaps these pieces are invitations to us, to join him.

Rusty and other tales of the Virus

by Christina Waters | Apr 12, 2020 | Home |

Rusty came on our walk this morning.

When you’re an adult women without children or pets, you name your hats. And your car, your plants, your pillows, even your laptop.

Rusty came from Switzerland, he’s red and woolly and sits strangely on my small head.

Still he has had a colorful life thus far. Rusty was born in San Gallen, near the Italian border where we went for New Year’s after spending Christmas in Bologna. The year after the turn of the millennium.

He experienced his first snow on New Year’s Day and has since come with me to Death Valley, also at New Year’s, and to the Mojave, and England, and along the Pogonip Trail in rainy winter weather.

My four pomegranate seedlings—now almost 5 years old—are named Pom, Pom-Pom, Pometto, and Pompeo. It took us a full year just to remember which was which. But they liked having names and responded to being given such attention. Now they are quite large.

Grape, my purple velour throw pillow, has been with me for 40 years, with two changes of stuffing, six changes of men, and several major mendings.

Life is tastier when beloved objects have names. They become part of your life in an intimate way. They become persons. You expand yourself in unexpected ways through your companion pillows, plants, clothing, and special mementos.

I can’t imagine the poverty of a life containing only things, objects, rather than special friends and identifiable companions. I might be odd, but there it is.

The more I love my named entities, the harder it becomes to let them go. They become irreplaceable, far from being stuff you can exchange for newer stuff, or cleaner stuff without so many stains.

Think of your favorite sweater. It’s not perfect. It has stains, it has holes, it’s been mended. A lot.

Yet these are not good enough reasons to let it go. Au contraire. Each sign of weathering shows how much your have worn it, how far it has traveled with you. Your life is contained within its seams and stitching.

Just touching Grape brings back memories of times when I lived in a patchouli-scented log cabin in the woods. No money, no vintage wines, just elderflower tea and hash.

When I wear Rusty I can smell the snow of New Year’s Day in Switzerland.

Of course it’s neurotic to live this way. Also rich and joyful.

Oscars 2020: A few choice remarks

by Christina Waters | Feb 7, 2020 | Home |

Yes, Brad Pitt should win the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his deceptively casual turn in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time In ….Hollywood. A fairytale about the way movies were, or might have been made, with a fairytale ending. A “just so” story that takes one of the meatiest horror stories in mid-20th century America—the true life massacre of Sharan Tate et al. by the Manson Family—and massages it until it implodes into a magic realist ending. Oh the horror is still there, but not where we expect it.

The cool thing about Pitt’s performance is its maturity, utter confidence, and delicious surprise. Oh we knew he had the stuff back when his mind came loose in 12 Monkeys, and when he left it all on the floor in Fight Club. But then we lost sight of that Brad Pitt, and replaced him with Angelina Jolie’s arm candy. We did what some male chauvinists do to women—we dismissed him as simply an object. A dreamy one, to be sure. But still an object.

Well, director Tarantino remembered the actor slumbering under all that Armani, and that’s the guy who turned up to match wits and instincts with Leo DiCaprio in Tarantino’s film.

My pick for Best Actor is the astonishing Antonio Banderas who probably doesn’t have a chance because the Academy likes over the top chew the chandeliers performances like Joaquin Phoenix in The Joker. Phoenix will win, but Banderas was flawless—flawless, exposed, and touching as director Almadovar’s surrogate in a beautiful film, Pain and Glory.

As for Best Actress, frankly I’m at a loss. I didn’t see all of the nominees this year, between failure of films to appeal to me and having hand surgery, it wasn’t my most movie-filled year. I DO know that the ultra-camp, unconvincing Renée Zellweger (who’s sure to win, apparently) should not win. She was in my opinion grotesque as the divine and vulnerable Judy Garland. Just silly drag stuff and she sang Judy’s songs!!! Perhaps she should win for the chutzpah to cover one of the great singers of the American songbook.

And while I adore Saoirse Ronan, this wasn’t her best outing either.

In fact, I’ll go further and buck the critical tide: I wasn’t as impressed with Greta Gerwig’s ambitious revival of Little Women as I’d hoped to be. It felt too contrived, almost Hallmarkean in its earnest faithfulness to the period. I also thought there was a lot of miscasting in Gerwig’s film. Timothée Chalamet was too fragile to be believed, and Florence Pugh was too modern and mature to be credible as the younger sister.

In the Supporting Actor category, Pitt’s competition is pretty powerful I gotta say. I mean who doesn’t love the colossal Tom Hanks? Al Pacino and Joe Pesci will probably cancel each other out and the day Anthony Hopkins convinces me that he’s a pope…..So I’m still with Brad Pitt for Supporting Actor.

As for Best Supporting Actress. Full disclosure: I did not see Marriage Story, which at first I didn’t even want to see, and then when I became intrigued, had already left town. But given Laura Dern’s mastery of every role she’s ever played, she might just take this one. On the other hand, Kathy Bates is god. So….up for grabs.

Best Director? Well if Sam Mendes doesn’t win for 1917, then it should go to Bong Joon Ho whose brilliant urban myth Parasite shattered all kinds of conventions, styles, and expectations.

Best Picture? Again, I didn’t see most of the entries, but given the recent awards thrown at 1917, it seems quite likely that Sam Mendes’

haunting study of the young men who fought “over there” could take it. But it really should go to Bong Joon Ho, whose film remains one of the finest most complex I’ve seen in a decade. Any decade.

Parasite: a 21st Century Fable

by Christina Waters | Nov 15, 2019 | Art, Home |

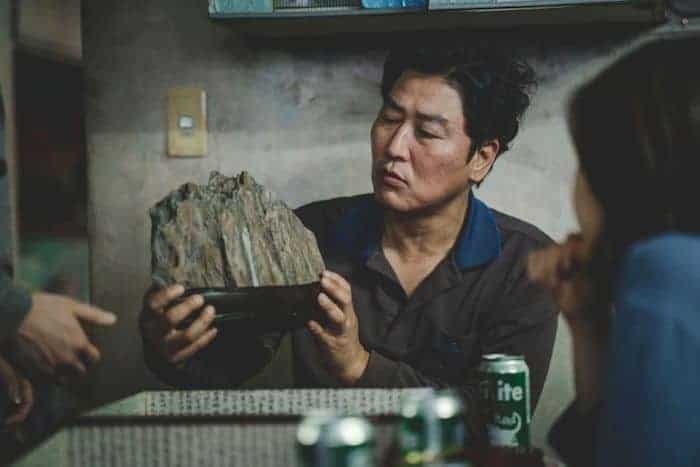

Parasite, the new film by Korean auteur director Bong Joon Ho, is not only gorgeous to look at, it presents a harrowing satire on the state of class inequity in the 21st century. It’s hard to think of a recent film that packs this much metaphorical power. Set in Korea in the midst of a Dickensian disparity of wealth—the Kims live in basement squalor, the Parks live in upscale serenity. But it could be anywhere in the first world. It is here, right now, and that very fact provides the razor edge of recognition audiences feel in response to this darkly comic/existential romp that snatched the Cannes Festival’s Palme d’Or away from Quentin Tarantino (See my review of Tarantino’s “Once upon a time in Hollywood”.)

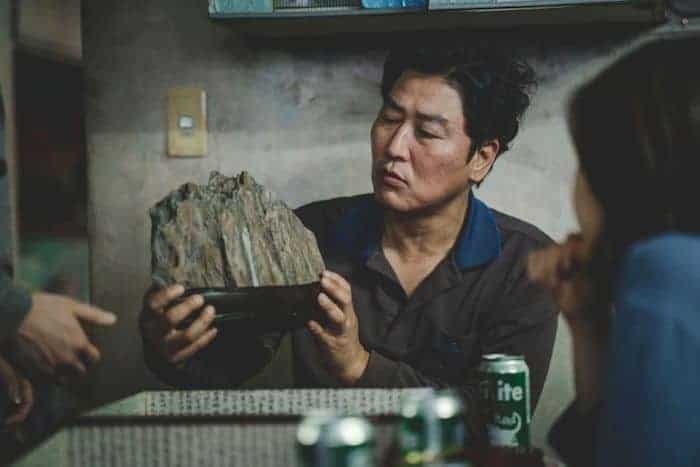

Parasite is a tale told through two families: the luckless, unemployed Kim Family headed by the extraordinary Kang-Ho Song as the father, Kim Chung-Sook as his wife, Choi Woo-Shik as teenaged son “Kevin” and Park So-Dam as his crafty hacker sister “Jessica. Determined to claw their way out of their ghetto squalor, the Kims scheme their way (I won’t spoil it) into the lives of the wealthy Park Family, led by Cho Yeo-jeong as the naive, lovely Mrs. Park and Lee Sun Gyun as style-conscious CEO Mr. Park.

Before you know it the Kims, who’ll literally do anything to make money, manage to insinuate themselves into the heart of the Park’s splendid household. It is a symbiotic ecosystem made in the hellishly brilliant imagination of this director.

Before you know it the Kims, who’ll literally do anything to make money, manage to insinuate themselves into the heart of the Park’s splendid household. It is a symbiotic ecosystem made in the hellishly brilliant imagination of this director.

[Above we find the resourceful Kim siblings finding the best signal from their neighbor’s wifi right above the toilet.]

Mr. Kim becomes Mr. Park’s driver, Mrs. Kim is the new Park housekeeper after cleverly managing to get the former one fired (the scenes here are laugh out loud funny). The son becomes tutor (and lover) to the Park’s daughter, and his sister poses as an art therapist for the Park’s young son, who is obsessed with American Indians.

The house itself is a key player in what will reveal itself to be Bong’s sly-handed tale of social inequity. An architectural masterpiece (designed by director Bong and made especially for the film) the sleek modernist house is laid out in interlocking levels. The living room’s enormous wall of glass overlooks an oasis of green lawn bordered by a manicured hedge.

The house itself is a key player in what will reveal itself to be Bong’s sly-handed tale of social inequity. An architectural masterpiece (designed by director Bong and made especially for the film) the sleek modernist house is laid out in interlocking levels. The living room’s enormous wall of glass overlooks an oasis of green lawn bordered by a manicured hedge.  This hermetic world insulates the Parks from any unsightly social reality and makes a painful contrast to the mess and chaos of the Kim’s basement apartment. Most importantly to the director’s storytelling, the house also contains a secret passage into yet another domain—and a ghastly secret buried deep within the heart of lavish wealth.

This hermetic world insulates the Parks from any unsightly social reality and makes a painful contrast to the mess and chaos of the Kim’s basement apartment. Most importantly to the director’s storytelling, the house also contains a secret passage into yet another domain—and a ghastly secret buried deep within the heart of lavish wealth.

Bong’s social commentary is never heavy handed, but it spares no one.

How this secret is discovered, what it contains, and where its layered metaphors lead are the elements driving a tsunami of loss, compassion, violence, joy, and ultimately a fairytale ending.

Parasite is powered by poetic cinematography, scored with Western classical music (another edgy dig at Korean social pretentions) and acted by a cast of brilliant players as capable of slapstick as heartbreak. I laughed my way through this film, even during its most terrifying scenes. The two families and the social codes they embody are turned inside out more than once, and never in predictable ways. All the actors are memorable, but especially lead player Kang-Ho Song, Mr. Kim [above], a frequent Bong collaborator. His broad face is roadmap of dashed dreams. As expressive as any Willem Dafoe, a savage/tender mirror reflecting Mr. Kim’s transformation—and his realization that his family’s larceny has triggered untold psychic damage. Nothing in Mr. Kim’s life has ever worked out, and Song’s face ultimately reveals despair on a Kierkegaardian scale. A great actor in a part worthy of his astonishing gifts.

Near the end of Parasite we find that just desserts are the main course of an outdoor birthday party for the spoiled Park son.  And once the shocking visual pyrotechnics have cooled down, the film draws to a haunting, eloquent close a la Charles Dickens. Desperate and ephemeral dreams, of the sort that reveal how much the rich and the poor are mutually bound in a slow dance of need, greed, hypocrisy, and desire.

And once the shocking visual pyrotechnics have cooled down, the film draws to a haunting, eloquent close a la Charles Dickens. Desperate and ephemeral dreams, of the sort that reveal how much the rich and the poor are mutually bound in a slow dance of need, greed, hypocrisy, and desire.

Parasite is a stunning cinematic fable, brilliant in every way, and for my money….unforgettable.

Before you know it the Kims, who’ll literally do anything to make money, manage to insinuate themselves into the heart of the Park’s splendid household. It is a symbiotic ecosystem made in the hellishly brilliant imagination of this director.

Before you know it the Kims, who’ll literally do anything to make money, manage to insinuate themselves into the heart of the Park’s splendid household. It is a symbiotic ecosystem made in the hellishly brilliant imagination of this director.

The house itself is a key player in what will reveal itself to be Bong’s sly-handed tale of social inequity. An architectural masterpiece (designed by director Bong and made especially for the film) the sleek modernist house is laid out in interlocking levels. The living room’s enormous wall of glass overlooks an oasis of green lawn bordered by a manicured hedge.

The house itself is a key player in what will reveal itself to be Bong’s sly-handed tale of social inequity. An architectural masterpiece (designed by director Bong and made especially for the film) the sleek modernist house is laid out in interlocking levels. The living room’s enormous wall of glass overlooks an oasis of green lawn bordered by a manicured hedge.

And once the shocking visual pyrotechnics have cooled down, the film draws to a haunting, eloquent close a la Charles Dickens. Desperate and ephemeral dreams, of the sort that reveal how much the rich and the poor are mutually bound in a slow dance of need, greed, hypocrisy, and desire.

And once the shocking visual pyrotechnics have cooled down, the film draws to a haunting, eloquent close a la Charles Dickens. Desperate and ephemeral dreams, of the sort that reveal how much the rich and the poor are mutually bound in a slow dance of need, greed, hypocrisy, and desire.