by Christina Waters | Jan 28, 2017 | Art, Home |

Directed by Garth Davis and adapted from the true story “A Long Way Home,” Lion tells the fairytale saga of a young Indian boy, Saroo Brierley, who becomes lost a thousand miles away from his village, and is miraculously adopted by an Australian couple. After many harrowing misadventures as well as endearing capers, the film hands us over to the grown-up Saroo, now in college in Melbourne. Though his Australian family have been loving and supportive, Saroo increasingly burns with the need to find his Indian home, to find his mother and brother and let them know that he is alive and well.

That’s the set-up— but the film is by no stretch simply a beautifully told tale of a “lost boy” and his quest for home. Powered by urgent cinematography of chaotic Calcutta and the breathtaking coastline of Tasmania, Lion is graced with a suite of outstanding performances. Especially those of captivating young Sunny Pawar as the five-year-old Saroo, and Dev Patel as 26-year-old Saroo—but also a never-better Nicole Kidman as Saroo’s adoptive mother and Rooney Mara as Saroo’s college girlfriend.

It’s always tricky casting two strong actors as a single character, the young version and then later the character as an adult. Tricky because as we fall in love with the first version—in this case the astonishingly poised and playful Pawar—it can be wrenching to accept the character newly matured in the formidable screen presence of Patel, who is all grown up from his days stealing scenes in Slumdog Millionaire and The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. An exciting actor, the adult Patel exudes surprising sex appeal and knows how to use one of the strongest, most expressive faces in film. Caravaggio paints Shiva.

It’s always tricky casting two strong actors as a single character, the young version and then later the character as an adult. Tricky because as we fall in love with the first version—in this case the astonishingly poised and playful Pawar—it can be wrenching to accept the character newly matured in the formidable screen presence of Patel, who is all grown up from his days stealing scenes in Slumdog Millionaire and The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. An exciting actor, the adult Patel exudes surprising sex appeal and knows how to use one of the strongest, most expressive faces in film. Caravaggio paints Shiva.

Reviewers have made much of this film as a tear-jerker, destined to reduce even the most jaded viewer to jelly. Certainly it can do that. But it’s complicated. There’s a Huck Finn quality to the nightmarish odyssey of the little boy, who goes out with his brother to seek any kind of work that will help keep themselves and their mother in food. He leaves one night with the beloved older brother, and ends up at a train station where the brother tells him to stay put. Little Saroo falls asleep and when he wakes up the brother is gone and he’s completely alone at the huge railway platform. Jumping into an empty train coach, he sleeps again—such a delicious fairytale—and when he wakes the train is moving. And it keeps on moving for days, all the while carrying him farther and farther away from home. Since he’s only a child, he has no way of knowing what has happened and where he is. And so things begin to unfold.

In true Dickens fashion, some of the strangers little Saroo meets are kind and helping. Others have darker purposes. These form the heart of the first half of the film, and watching the little boy running to, and from, a variety of situations is both nerve-wracking and exciting. The utterly darling Pawar has us in the palm of his hand and then his life suddenly blooms with the love and care of his new parents a world away.

Nicole Kidman knocked me out in all of her scenes, but the one in which she explains to the grown-up Saroo just why she wanted to adopt him will destroy you. Even as Virginia Woolf in The Hours she was never this present, this entirely focused upon a single idea as she is here. (There’s also a second adopted Indian brother who has “issues,” and even in a fairytale the path to maturity never runs smoothly.)

Nicole Kidman knocked me out in all of her scenes, but the one in which she explains to the grown-up Saroo just why she wanted to adopt him will destroy you. Even as Virginia Woolf in The Hours she was never this present, this entirely focused upon a single idea as she is here. (There’s also a second adopted Indian brother who has “issues,” and even in a fairytale the path to maturity never runs smoothly.)

Once Saroo/Patel begins his Google-enhanced quest to pinpoint where he might have gotten on the train all those years ago, and struggles to locate his home village, the film gains intensity. Of course we want to see how he will find his home, whether his family still lives, and we can taste the reunion he so needs. But somewhere in there a generic ending starts to form itself. Not every stitch ends up in a neat crochet, a few corners of credibility are cut, and yet. And yet. The resolution of the quest is as satisfying as any epic tale can get.

The film was loaded with highest quality everything. Story, cinematography, acting, music, direction—I left feeling better than I had when I arrived. Lion delivered everything a movie should. And I loved it.

(Only one of those obligatory “true story” film endings, where they show footage of the real people upon whose lives the film is based, threatened to destroy the spectacular saga we’d just seen. Note to directors: don’t do this. Resist the cornball desire to show us “the way they are today.” Just don’t do it.]

by Christina Waters | Jan 28, 2017 | Art, Home |

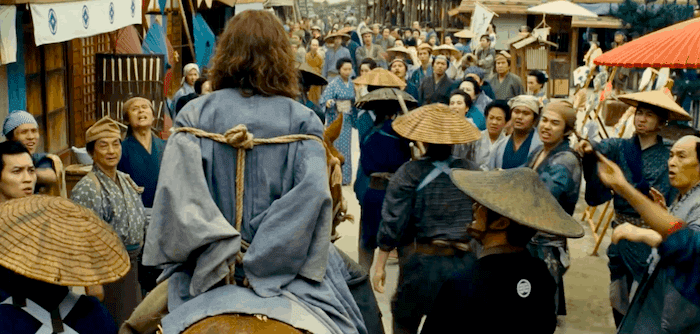

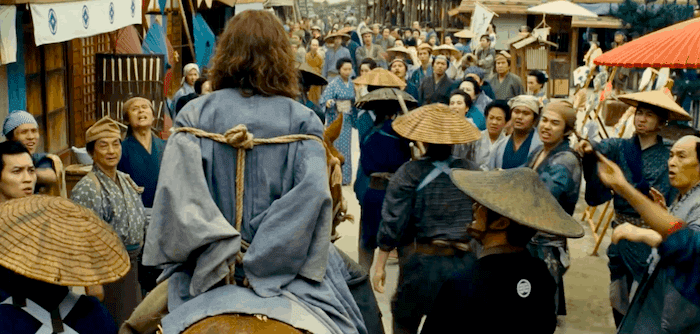

You can take the boy out of the Church, but you can’t take the Church out of Marty Scorsese. Fearless and probing, director Scorsese seems unstoppable in his restless (tormented?) quest for redemption. There have been other paths through his personal journey that circles around the miracle of the Christian resurrection. Good Fellas. The Wolf of Wall Street. The Last Temptation of Christ. But Silence is the most intimate, even in its monumental scale. Almost shocking in its adherence to religious ritual, prayer, ecclesiastical devotion, Silence portrays as much as it narrates an historic moment of brutal religious persecution—of Portuguese Jesuit missionaries by the dominant political structure of Japan, to whose shores the priests have come to convert poor peasants to the One True Faith.

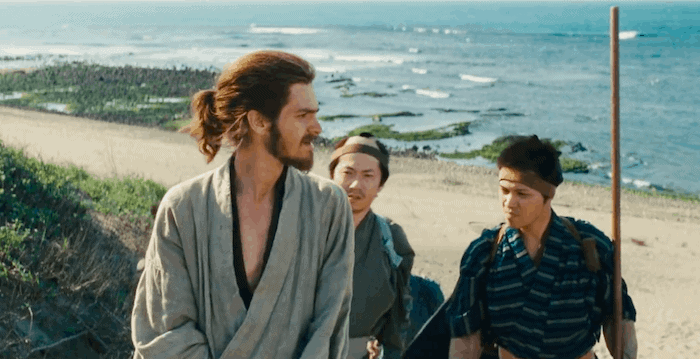

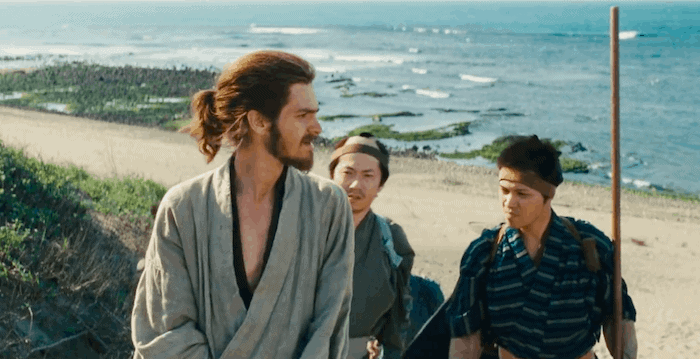

Andrew Garfield as Father Rodrigues and Adam Driver as Fr. Garrpe play 17th century priests on a quest to find their mentor and teacher Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson), rumored to have renounced his faith (apostasy, in Catholic terms) and not heard from in years. Such a quest—for a lost man of God, by two young and untried ministers—takes a resourceful storyteller through rich emotional and scenic landscapes. And Silence is stuptifyingly beautiful. Imagine an Ingmar Bergman meditation on lost faith and inner psychology, set in the atmospheric texture of Japan’s lakes, shores, volcanic terrain, and design-intensive interiors. It is gorgeous, gorgeous enough to take the Oscar for Best Cinematography, to be sure. Yet the healing benediction the director so desires—like the elusive and silent God he seeks— remains just off-screen.

Andrew Garfield as Father Rodrigues and Adam Driver as Fr. Garrpe play 17th century priests on a quest to find their mentor and teacher Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson), rumored to have renounced his faith (apostasy, in Catholic terms) and not heard from in years. Such a quest—for a lost man of God, by two young and untried ministers—takes a resourceful storyteller through rich emotional and scenic landscapes. And Silence is stuptifyingly beautiful. Imagine an Ingmar Bergman meditation on lost faith and inner psychology, set in the atmospheric texture of Japan’s lakes, shores, volcanic terrain, and design-intensive interiors. It is gorgeous, gorgeous enough to take the Oscar for Best Cinematography, to be sure. Yet the healing benediction the director so desires—like the elusive and silent God he seeks— remains just off-screen.

[I’ll get back to my main commentary in a minute, but let me digress. Never has an audience been dragged through the spectacle of so much mud, so much rain, so many bad hair days, so many painfully skinny bodies, and such brutally thick accents as in Silence. So closely does Scorsese’s loveletter adhere to the faith he can’t quite abandon that you can practically walk the Stations of the Cross in the 2 hours + of the film. Frankly, I admire all of that, the willingness to set irony aside and devoutly detail the deep tissue message of Christian martyrdom, the charity extended to one’s enemies, the absolution granted even to serial liars and thieves. But can we talk about casting?

Scorsese insisted on casting fine Japanese actors in the appropriate roles. Alas, during much of the film these same actors speak their lines in English. Incomprehensible English. This was surely the time for subtitles Marty! The main protagonist, the priest upon whose skinny shoulders the tale hangs is played by puppy-dog visaged Andrew Garfield. He acts his guts out and is incredibly convincing as a priest pushed to the very gates of hell, but his face is so weak that the film caves in during his extended scenes of captivity and philosophical dialogue with Buddhist honchos. He is seriously unappealing. (See my review of Lion, where we would follow the compelling Dev Patel anywhere. I would follow the chinless Garfield nowhere. Perhaps this is simply a matter of taste, but I doubt it.)

The most egregious casting woe is, in two words, Liam Neesom. As the apostate priest/mentor, finally discovered in an upscale domicile of Buddhist temple elite, Neeson looks as much like a Porteguese friar as do I, the product of Norwegian/Scottish-Irish ancestors. Give me a break. Plus his sorrow-ravaged face appears to be permanently dialed to “agony.”

The most egregious casting woe is, in two words, Liam Neesom. As the apostate priest/mentor, finally discovered in an upscale domicile of Buddhist temple elite, Neeson looks as much like a Porteguese friar as do I, the product of Norwegian/Scottish-Irish ancestors. Give me a break. Plus his sorrow-ravaged face appears to be permanently dialed to “agony.”

We, the audience, want to love everything that Martin Scorsese does. We endure beheadings, torture by water, by fire, by mud. We endure the sight of Adam Driver’s ribcase and Andrew Garfield’s chipmonk cheeks. But it’s hard to endure Liam Neeson’s massive Irish frame and face pretending to look Portuguese. Where was Antony Banderas when this film was cast? I know he can’t act but he sure can look authentically Portuguese.

Okay. Here’s my summary. Silence was as elegaic a film as it is possible to make. The music alone was transcendent. It was terrific to hear so much of the Catholic mass actually said in Latin (devotees of old school Catholicism will be thrilled), and I found my eyes deeply comforted by the impeccable design of Japanese interiors. The ocean never looked better. But I couldn’t recommend this film with any enthusiasm. Cinematographic geeks definitely will want to check it out. Everybody else, probably not. I would recommend streaming Scorsese’s actual religious masterpiece, The Last Temptation of Christ, and feasting on what sensual apostasy can look like when it’s done with religious fervor. And by Willem Dafoe.

by Christina Waters | Dec 26, 2016 | Art, Home |

It’s taken a week for me to recover from the emotional impact of this film. The unflinching tale of a family’s tribulation and one man’s inescapable heartbreak is easily the finest film I’ve seen in 2016, showcasing not only director/writer Kenneth Lonergan‘s deft weaving of pain and memory but a powerful central performance by Casey Affleck. Affleck is Lee Chandler whose older brother Joe (Kyle Chandler) has suddenly died leaving Lee the sole guardian of his nephew Patrick (Lucas Hedges).

For reasons we only gradually come to understand, Lee has been working as a janitor and handy man in Boston, and leaves to return to his New England hometown Manchester by the Sea to settle his brother’s estate and get his restless nephew in gear. The nephew and uncle, forced together by death, begin an awkward attempt at achieving some sort of bond, and their struggle to accept each other forms the mesmerizing heart of the film.

For reasons we only gradually come to understand, Lee has been working as a janitor and handy man in Boston, and leaves to return to his New England hometown Manchester by the Sea to settle his brother’s estate and get his restless nephew in gear. The nephew and uncle, forced together by death, begin an awkward attempt at achieving some sort of bond, and their struggle to accept each other forms the mesmerizing heart of the film.

Lonergan’s directorial magic lies in opening the story simply, letting us very gradually fall under the spell that Affleck’s raw affect and simple gestures create. His face reveals—or conceals—a catastrophic past that defines the rest of his life. Only gradually, stitching back and forth, moving through time in the non-linear way of real life, does the film show us the source of Lee’s pain. We begin to understand why the nephew and uncle are so haunted by tragedy, and why they keep moving closer to some kind of relationship that might, just might overcome all the pain.

The film, whose plot sounds searingly downbeat, is a work of genuine incandescence. Manchester by the Sea is a beautiful piece of filmmaking. It sails easily on the simple clarity of the coastal setting, the bare and poignant winter landscape, the bits of easy humor as we watch young Patrick’s attempt to navigate his high school popularity despite his father’s death. We learn that Patrick has an estranged mother, that Lee has an estranged ex-wife, played with uneven passion by Michelle Williams. The situation grows clearer with each scene.

The film, whose plot sounds searingly downbeat, is a work of genuine incandescence. Manchester by the Sea is a beautiful piece of filmmaking. It sails easily on the simple clarity of the coastal setting, the bare and poignant winter landscape, the bits of easy humor as we watch young Patrick’s attempt to navigate his high school popularity despite his father’s death. We learn that Patrick has an estranged mother, that Lee has an estranged ex-wife, played with uneven passion by Michelle Williams. The situation grows clearer with each scene.

But it is Casey Affleck’s film. Every moment, every nuance of devastation, every implication of a personal world lost is etched on his raw face, a face equally capable of existential confusion and gentle hope. His is an effortless performance of desperation and occasionally uncontrolled rage, and the director seems to know better than to interfere. The film refuses to smooth the edges of life that happens in the way that all life does. Chance intervenes and everything changes. Nothing is ever the same. Yet life continues. An uncontrived loveletter to the pain of being human, Manchester is a film I need to see many more times. It feeds some need deeper than that for cheap laughs and fairytale endings. Go see it before the Oscars.

But it is Casey Affleck’s film. Every moment, every nuance of devastation, every implication of a personal world lost is etched on his raw face, a face equally capable of existential confusion and gentle hope. His is an effortless performance of desperation and occasionally uncontrolled rage, and the director seems to know better than to interfere. The film refuses to smooth the edges of life that happens in the way that all life does. Chance intervenes and everything changes. Nothing is ever the same. Yet life continues. An uncontrived loveletter to the pain of being human, Manchester is a film I need to see many more times. It feeds some need deeper than that for cheap laughs and fairytale endings. Go see it before the Oscars.

by Christina Waters | Jan 29, 2016 | Art, Home |

Paintings by Frank Galuszka—from the lake district of Italy to the Davenport coast— at Gabriella Cafe, January through March 2016.

by Christina Waters | Dec 3, 2015 | Art |

UCSC’s notoriously ambitious Concert Choir—under the direction of Nathaniel Berman—works its way gracefully through some outstanding Baroque oratorios, works from the A-list of the 17th century—Scarlatti, Carissimi, Schütz and Charpentier—on Friday December 4th, 7:30pm at the Music Center Recital Hall.

UCSC’s notoriously ambitious Concert Choir—under the direction of Nathaniel Berman—works its way gracefully through some outstanding Baroque oratorios, works from the A-list of the 17th century—Scarlatti, Carissimi, Schütz and Charpentier—on Friday December 4th, 7:30pm at the Music Center Recital Hall.

A feast for the senses, the perfect opening act for all the holiday festivities to come.

by Christina Waters | Sep 3, 2014 | Art |

It’s always tricky casting two strong actors as a single character, the young version and then later the character as an adult. Tricky because as we fall in love with the first version—in this case the astonishingly poised and playful Pawar—it can be wrenching to accept the character newly matured in the formidable screen presence of Patel, who is all grown up from his days stealing scenes in Slumdog Millionaire and The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. An exciting actor, the adult Patel exudes surprising sex appeal and knows how to use one of the strongest, most expressive faces in film. Caravaggio paints Shiva.

It’s always tricky casting two strong actors as a single character, the young version and then later the character as an adult. Tricky because as we fall in love with the first version—in this case the astonishingly poised and playful Pawar—it can be wrenching to accept the character newly matured in the formidable screen presence of Patel, who is all grown up from his days stealing scenes in Slumdog Millionaire and The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. An exciting actor, the adult Patel exudes surprising sex appeal and knows how to use one of the strongest, most expressive faces in film. Caravaggio paints Shiva. Nicole Kidman knocked me out in all of her scenes, but the one in which she explains to the grown-up Saroo just why she wanted to adopt him will destroy you. Even as Virginia Woolf in The Hours she was never this present, this entirely focused upon a single idea as she is here. (There’s also a second adopted Indian brother who has “issues,” and even in a fairytale the path to maturity never runs smoothly.)

Nicole Kidman knocked me out in all of her scenes, but the one in which she explains to the grown-up Saroo just why she wanted to adopt him will destroy you. Even as Virginia Woolf in The Hours she was never this present, this entirely focused upon a single idea as she is here. (There’s also a second adopted Indian brother who has “issues,” and even in a fairytale the path to maturity never runs smoothly.)

Andrew Garfield as Father Rodrigues and Adam Driver as Fr. Garrpe play 17th century priests on a quest to find their mentor and teacher Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson), rumored to have renounced his faith (apostasy, in Catholic terms) and not heard from in years. Such a quest—for a lost man of God, by two young and untried ministers—takes a resourceful storyteller through rich emotional and scenic landscapes. And Silence is stuptifyingly beautiful. Imagine an Ingmar Bergman meditation on lost faith and inner psychology, set in the atmospheric texture of Japan’s lakes, shores, volcanic terrain, and design-intensive interiors. It is gorgeous, gorgeous enough to take the Oscar for Best Cinematography, to be sure. Yet the healing benediction the director so desires—like the elusive and silent God he seeks— remains just off-screen.

Andrew Garfield as Father Rodrigues and Adam Driver as Fr. Garrpe play 17th century priests on a quest to find their mentor and teacher Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson), rumored to have renounced his faith (apostasy, in Catholic terms) and not heard from in years. Such a quest—for a lost man of God, by two young and untried ministers—takes a resourceful storyteller through rich emotional and scenic landscapes. And Silence is stuptifyingly beautiful. Imagine an Ingmar Bergman meditation on lost faith and inner psychology, set in the atmospheric texture of Japan’s lakes, shores, volcanic terrain, and design-intensive interiors. It is gorgeous, gorgeous enough to take the Oscar for Best Cinematography, to be sure. Yet the healing benediction the director so desires—like the elusive and silent God he seeks— remains just off-screen. The most egregious casting woe is, in two words, Liam Neesom. As the apostate priest/mentor, finally discovered in an upscale domicile of Buddhist temple elite, Neeson looks as much like a Porteguese friar as do I, the product of Norwegian/Scottish-Irish ancestors. Give me a break. Plus his sorrow-ravaged face appears to be permanently dialed to “agony.”

The most egregious casting woe is, in two words, Liam Neesom. As the apostate priest/mentor, finally discovered in an upscale domicile of Buddhist temple elite, Neeson looks as much like a Porteguese friar as do I, the product of Norwegian/Scottish-Irish ancestors. Give me a break. Plus his sorrow-ravaged face appears to be permanently dialed to “agony.”

For reasons we only gradually come to understand, Lee has been working as a janitor and handy man in Boston, and leaves to return to his New England hometown Manchester by the Sea to settle his brother’s estate and get his restless nephew in gear. The nephew and uncle, forced together by death, begin an awkward attempt at achieving some sort of bond, and their struggle to accept each other forms the mesmerizing heart of the film.

For reasons we only gradually come to understand, Lee has been working as a janitor and handy man in Boston, and leaves to return to his New England hometown Manchester by the Sea to settle his brother’s estate and get his restless nephew in gear. The nephew and uncle, forced together by death, begin an awkward attempt at achieving some sort of bond, and their struggle to accept each other forms the mesmerizing heart of the film. The film, whose plot sounds searingly downbeat, is a work of genuine incandescence.

The film, whose plot sounds searingly downbeat, is a work of genuine incandescence.  But it is Casey Affleck’s film. Every moment, every nuance of devastation, every implication of a personal world lost is etched on his raw face, a face equally capable of existential confusion and gentle hope. His is an effortless performance of desperation and occasionally uncontrolled rage, and the director seems to know better than to interfere. The film refuses to smooth the edges of life that happens in the way that all life does. Chance intervenes and everything changes. Nothing is ever the same. Yet life continues. An uncontrived loveletter to the pain of being human, Manchester is a film I need to see many more times. It feeds some need deeper than that for cheap laughs and fairytale endings. Go see it before the Oscars.

But it is Casey Affleck’s film. Every moment, every nuance of devastation, every implication of a personal world lost is etched on his raw face, a face equally capable of existential confusion and gentle hope. His is an effortless performance of desperation and occasionally uncontrolled rage, and the director seems to know better than to interfere. The film refuses to smooth the edges of life that happens in the way that all life does. Chance intervenes and everything changes. Nothing is ever the same. Yet life continues. An uncontrived loveletter to the pain of being human, Manchester is a film I need to see many more times. It feeds some need deeper than that for cheap laughs and fairytale endings. Go see it before the Oscars.