by Christina Waters | Oct 1, 2016 | Home |

It usually begins with something written down longhand. I take it up to my computer, apply a little blind faith and just begin in-putting what’s written on the page. Then something clicks and I’m expanding those ideas without actually thinking. Something else has taken over. The consciousness that surrounds my body and magically connects instinct with a huge stream of words. In that connection, there is no more Self. Just the words flowing out of my hands. And when it stops — usually all by itself— I regain my consciousness, look at what’s written on the screen and wonder how it got there.

When the zone takes over, I have no memory of having written those words. And when I discover that they’re good, I just grin. And grin.

by Christina Waters | Sep 30, 2016 | Home |

A college birthday party featuring tequila, piñatas and sombreros is branded “an act of ethnic stereotyping.” The perpetrators are branded racists, their party deemed an act of “cultural appropriation.” Thus begins writer Lionel Shriver’s piercing critique in The Guardian of Identity Politics and its sweaty-palmed encroachment on the realm of fiction.

If we embrace narrow group-based identities too fiercely, we cling to the very cages in which others would seek to trap us. We pigeonhole ourselves. We limit our own notion of who we are, and in presenting ourselves as one of a membership, a representative of our type, an ambassador of an amalgam, we ask not to be seen.

My sister and I, back in the innocence of the early 60s, loved to comb through a trunk of colorful clothing in order to “dress up” as “gypsies.” Two lily-white-skinned little girls clad in long skirts, hoop earrings and bandanas prancing around an attic playroom—oh yes, we were serious emerging racists.

Or were we simply making believe? Applying our growing and eager imaginations to the task of pretending to be something, someone exotic and other just to see if we could convince ourselves of fictional identities. Yes, that was it. We were exercizing our imaginations—the intellectual skills that would guarantee our ability to envision new things, empathize with new people and beings other than ourselves.

The strangle-hold of academia’s repudiation of play, fictive theatrics, not to mention colorful and original dress codes, has almost destroyed whatever might remain of open minds and creative inquiry. The lock-step of identity politics has exceeded its 15 minutes. Confining individuals in stockades of broad bandwidth “identities,” pretty much guarantees that students will be unable to discover who they might have been before they were caged in generic silos.

Those who embrace a vast range of “identities†– ethnicities, nationalities, races, sexual and gender categories, classes of economic under-privilege and disability – are now encouraged to be possessive of their experience and to regard other peoples’ attempts to participate in their lives and traditions, either actively or imaginatively, as a form of theft.

Shriver speaks for me, and many others who are weary and beyond impatient with the persistence of intellectual censorship when she hopes that, “the concept of ‘cultural appropriation’ is a passing fad: people with different backgrounds rubbing up against each other and exchanging ideas and practices is self-evidently one of the most productive, fascinating aspects of modern urban life.”

I’d add that this flirtation of and with difference is the most fascinating—and foundational—aspect of fictional literature, drama, filmmaking, painting, composing, et al. Without being able to imagine characters different from ourselves, or from anyone we’ve ever known, our consciousness – and our ability to dream other worlds – would atrophy.

by Christina Waters | Sep 26, 2016 | Home |

In a smart and emotional article in New York Magazine, Andrew Sullivan concludes:

There are books to be read; landscapes to be walked; friends to be with; life to be fully lived. And I realize that this is, in some ways, just another tale in the vast book of human frailty. But this new epidemic of distraction is our civilization’s specific weakness. And its threat is not so much to our minds, even as they shape-shift under the pressure. The threat is to our souls.

He is bordering the territory I explore in my forthcoming book, Inside the Flame, tracking the erosion of human interaction, of rich sensory experiences created by spending our lives bombarded with, and connected to electronica. Worse—it’s addictive, and even though my book is devoted to direct discovery of the tactile world, I admit that I spend far too much time lurking around the political miasma-du-jour, celebrity break-ups, cinema backstories, and just about anything Zappos wants to tempt me with. (to be continued)

by Christina Waters | Sep 4, 2016 | Home |

Many people feel that the time they spend at work is essentially wasted — they are alienated from it, and the psychic energy invested in the job does nothing to strengthen their self. For quite a few people free time is also wasted. Leisure provides a relaxing respite from work, but it generally consists of passively absorbing information, without using any skills or exploring new opportunities for action. As a result life passes in a sequence of boring and anxious experiences over which a person has little control.

That’s a quote from a famous book called Flow, by a man with a complicated name, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (I’ll just refer to him as M.C.).

Let’s unpack this for a moment. Yes, absolutely most people feel that time spent at work (which I’m assuming is a 9 to 5 situation) is “essentially wasted.” And it’s work in which our emotions and creativity are rarely engaged, e.g. administration, shipping and receiving, prepping ingredients at the restaurant.

M.C. goes on to say that many of us also waste our free time, the so-called “down time” in which we can do whatever we please outside the narrow, drab sphere of the workplace. He points out that (more…)

by Christina Waters | Sep 3, 2016 | Home |

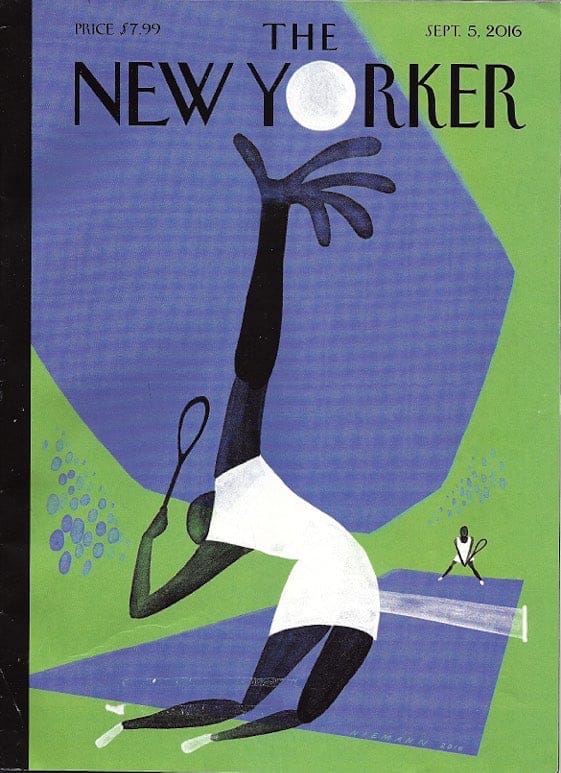

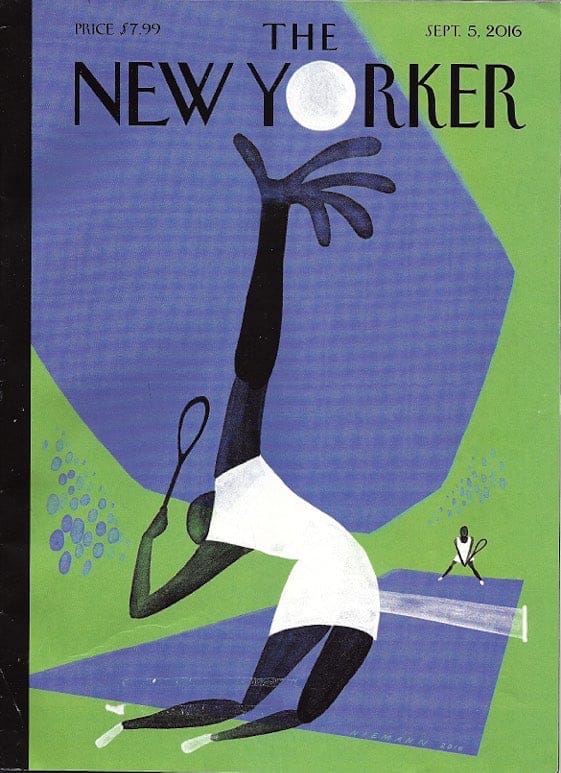

The current New Yorker cover illustration by Christoph Niemann brought back a tingling rush of pleasure for those long summer days during graduate school when I played more than my fair share of tennis.

The body’s arc of contraposto just before letting loose the serve, the ball tossed to the exact point in space where the racquet would soon hit. The illustration is a master class in graphic design. Minimum of shapes and colors. The long reach of the arm almost pushing through the magazine cover. The beautiful expanse of sky blue, echoed by a gathering of blue ovals to suggest the crowds watching the U.S. Open. I can feel the heat and the tension of the game. The crowning achievement of this delicious image is the placement of the tennis ball—exactly on the spot of the “O” in “YORKER.” A slam dunk for the eyes!

You can watch an animated version of this illustration—or you can get out on the court and play!

by Christina Waters | Sep 1, 2016 | Home |

Screenwriter James Schamus turns director with this supple adaptation of the 2008 Philip Roth novel Indignation, starring Logan Lerman as socially innocent, intellectually precocious Marcus Messner, son of a kosher butcher from Newark, New Jersey. We meet Marcus as he prepares to leave home for a Winesburg Ohio college, thereby avoiding the Korean War draft. Both the father (played with incessant anxiety by Danny Burstein) and his wife (a smoldering Linda Emond) have high hopes for their brilliant son. Assigned to room with two other non-Gentiles, Marcus throws himself into his studies, rankles at the required chapel services, and finds himself entranced by Olivia, a blonde shiksa with sexual experience (a disarming Sarah Gadon).

Schamus has managed to pull off a tricky balance of Roth’s tangled portrait of a young man’s coming of age, against the backdrop of parents who no longer know him and the isolation of his uncompromising intelligence. After his uncomfortable dorm situation comes undone—triggered by an event of sexual candor between Marcus and his new girlfriend—the high-strung freshman is called into the dean’s office.

Well here the film dares to be true to its literary roots, (more…)