by Christina Waters | Sep 26, 2024 | Book, Home, Movies |

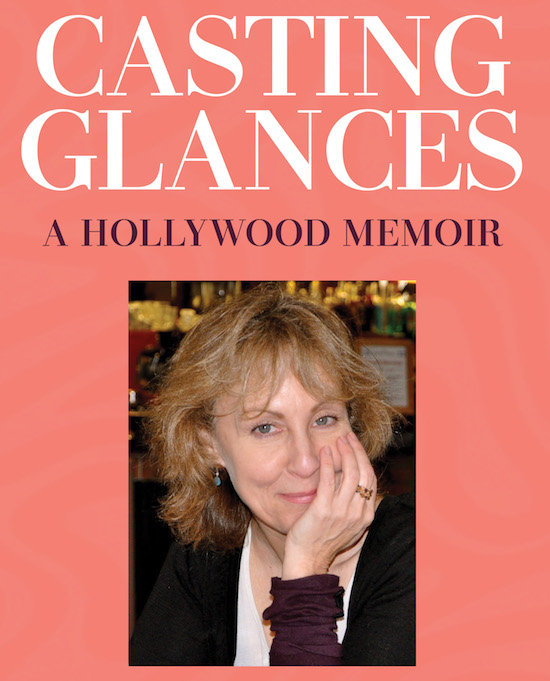

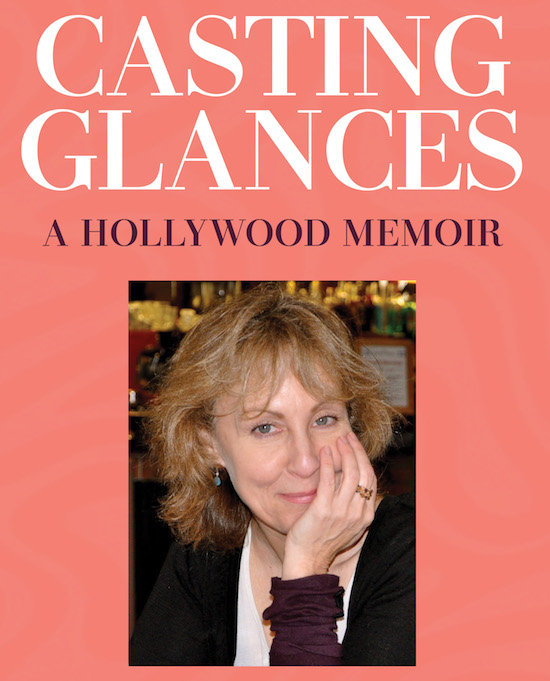

It’s been a long and winding road from Santa Cruz to Hollywood to Kazakhstan and back, but casting director Judy Bouley brought back hair-raising, spine-chilling, and joyous tales from her life in the movies. Casting Glances is the name of her just-released book—soon to be available on Amazon—and it’s loaded with tell-all back stories of Hollywood stars, extras, exotic locations, triumphs and screw-ups. But more than simply a collection of cinema gossip and rich travel lore, Bouley’s book boldly documents her own over-the-top professionalism, its implosion into emotional crisis, meltdown, healing, and ultimately post-COVID reality.

Having known Judy since our early acquaintance as founding members of the Santa Cruz Film Council some 40 years ago, I was eager to talk to her about the new book.

Q: I found it fascinating that a casting director doesn’t simply go out look for the right actors, give them to the director and the production team, and then move on. What happens once you find what you think are the right actors?

Bouley: Well, I work differently than most casting directors who hang out a shingle and have an office in Hollywood or New York and they don’t ever travel on location. I always stay with my films. People assume that we cast all the actors and extras before filming begins. Not true. I’ve had directors make revisions in the script and I was given 48 hours to find the right actors. They called me Mama Bouley on Master & Commander because I was always there for the background artists.The reason I stay on the set is that you never know—the director could have a new idea on Thursday, and you have to cast and be ready to go on Monday. I first got into casting with Lost Boys in Santa Cruz. I cast five speaking parts and 2200 background parts. And I did Star Trek IV and five films with Tom Hanks. The work is about relationships. Once they trust you the work starts flowing.

On The Polar Express we had thirty six cameras placed all around the set, digitally recording, many times per second, a 360-degree view of the actor’s movements. That digital information was collected via the sensors and then fed to a team of computer wizards who transfered the actors’ movements to a 3D model.”

Then they started flying me around. And then I ended up in Bulgaria, Morocco, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and I spent eleven months in Mexico on Master and Commander. I was there all the time to put out any fires before they started.

“My staff booked over two hundred men and boys for auditions in San Diego alone. From February to May we held casting calls in Baja, Los Angeles, Santa Cruz, Vancouver and Toronto. In all we processed close to a thousand hopefuls to cast fifty five main crew for Her Majesty’s ship, sixty ‘B’ crew for our battle scenes and two hundred and fifty French sailors.”

Bouley worked for almost a year, living on location, with the cast and crew of Master and Commander, directed by Austalian legend Peter Weir.  (Weir on right, with his cinematographer Russell Boyd.)

(Weir on right, with his cinematographer Russell Boyd.)

Q: How did that work? the huge old ship, huge cast and crew?

Bouley: We bought that ship in Rhode Island for $800,000 and we sailed it to the Panama Canal. Oh, my god, yeah. The real ship lived in Ensenada and then we built an identical ship in the tank that they built for Jim Cameron with Titanic. And then we put it on a gimbal, that’s a machine that moves the ship from left to right. It’s amazing. Maybe 150 construction workers built the replica ship, and then they cut it in three parts, and then they used the world’s biggest crane, and they put them in the tank, and then filled it with 600,000 gallons of water.

Q: You’ve had such a fascinating career working with iconic directors and actors, Robert Zemeckis, Peter Weir, Tom Hanks, Russell Crowe, Meryl Streep. Looking back do you think the pace of international assignments and deadlines burned you out?

Bouley: Absolutely. I’ve had an astounding four decades, and I’ve always been hired for the big ones and the hard ones, but it was a lonely existence. You live in the hotel, and then you get extra dirty underwear from Buenos Aires to Morocco. You get off the plane, and you do it again. And sadly, Christina, I did sort of out of sight, out of mind, where I’d only Skype my mother maybe every three weeks. Because, as you know, on a movie set, it’s this temporary intimacy with with everybody. You make them your temporary family. I was married to my career. If I could do it again, I’d do it differently.

“No matter where we were stationed, on the first day of school Mom reminded us, “Don’t get too close to your new friends because either their fathers or your dad will likely be transferred to their next assignment. You’ll just have to say goodbye. It’s better not to get close than to be broken hearted. Through most of my adult life I continued to carry out my mother’s questionable instructions. This contributed in part to my unsteady love relationships in which I had one foot in, one foot out. ‘Nice to meet you, where’s the exit?’ My father taught me to always keep my passport current and never own any more than I could pack in an afternoon.”

(Bouley, with young extras in India.)

(Bouley, with young extras in India.)

Q: The book also reveals intimate details of a lot of personal traumas and things suddenly breaking down with your longtime partner.

Bouley: I suffered through nine deaths. I helped every one of them through, through their death. I did The Way Back with Colin Farrell and that was my last one. That was three and a half years ago. There was COVID, and then there was the strike. And you would have thought that there would have been a collection of film offers on the table after that, but the studios aren’t into film anymore. They’re conglomerates. Universal is owned by Seagram, and they make a lot more money selling scotch than they do making Master and Commander.

(Bouley with actor Colin Farrell in Weir’s The Way Back)

(Bouley with actor Colin Farrell in Weir’s The Way Back)

Q: What did you want to do when you grew up?

Bouley: I wanted to be a social worker, which I was in Santa Cruz. I worked for Child Protection, and then I got laid off. That was in the mid-80s. So I went back to waiting tables at Cardinales on the wharf, and teaching jazzercise.

I got into this business because I volunteered for the Santa Cruz film festival, when Lost Boys came to town. They needed a location scout so they called Chamber of Commerce, and they called me. And I got paid $75 a day, and I got to wear a walkie talkie. In a way casting was still like doing social work, just using the vehicle of film. You can’t stay for 40 years with Child Protection, it’ll burn you out.

I met my business partner Dick Broder on the set of the Santa Cruz-based independent film Hard Traveling.

“I was doing the job of three people on the film: casting, props and catering at the whopping rate of $250.00 a week…essentially slave wages in the film business, even in 1984. “Hard Traveling” was a great crash course in what ‘not to do’ in film-making. Things on set were a chaotic mess. The assistant director was not pushing the director to stay on schedule. The director, being the director, wanted things his way. No one communicated well. The producer, was in over her head. In a word…messy.”

Q: How central was your stay at the Professionals in Crisis program at the Menninger Treatment Clinic to your ability to stabilize your career and self confidence?

Bouley: The mental health program at Menninger saved my life. The Professionals in Crisis program. I was in the program with 20 other people, including the CEO of NutraSweet, who showed me his $40,000 Rolex. So that proves he’s crazy. And Marissa Tomai’s boyfriend. That was when Peter Weir (my favorite director) hired me for The Way Back which we filmed in Bukgaria, Morocco and India. I also cast in Kazakhstan and Krygzystan for that film.

“At Menninger we had to eat three meals a day whether we wanted to or not. For the first week an aide sat next to me to make sure I chewed and swallowed. We were weighed twice a week. I came in at 99 lbs.”

It was right after my business partner, Dick, my best friend for 14 years, committed suicide. I had been on Road to Perdition shoot in Chicago for eight months, and we were literally shooting this scene where Tom Hanks kills Paul Newman, And then my phone rang, and it’s a detective. They found Dick in a hotel room. And, yeah, jeez. I couldn’t go back to film right away. It took me about 4 years to feel ready to go back to casting.

Q: I know you worked on this book for many years. And you include a memoir of your relationship with Dina Babbiott. How did that come about?

Off and on, it took 14 years to write this. You remember Dina Babbitt, who as a girl had been an artist in Auschwitz? She was living in the Santa Cruz Mountains at the time. Well Dina was really my Obi Wan Kenobi and we met when I lived with John (my cocaine addict, alcoholic Santa Cruz boyfriend). We met at an animation film festival. And then I lost track of her when I went on location, and then I was back in Santa Cruz and we reconnected, and she said, What’s your next movie? I said, I’m going to write your story. And she said, No, a lot of people have tried, and it was shitty. So I said, Well, it’s not going to be because I know you. We spent four months with me recording her, and practically living with her. But ultimately, it never got made.

I think the reason everybody can identify with this book is, ultimately, it’s a phoenix rising from the ashes story.

Q: What’s next? Will you continue with films, with casting?

Bouley: That’s what I’ll do. There’s usually 100 projects in Los Angeles. But you know, since COVID and since the strike, there are only seven feature films right now in Hollywood. Other places offer better tax incentives, like Boston, Atlanta, Canada and New Orleans.

Still, yes, it’s all I know how to do,

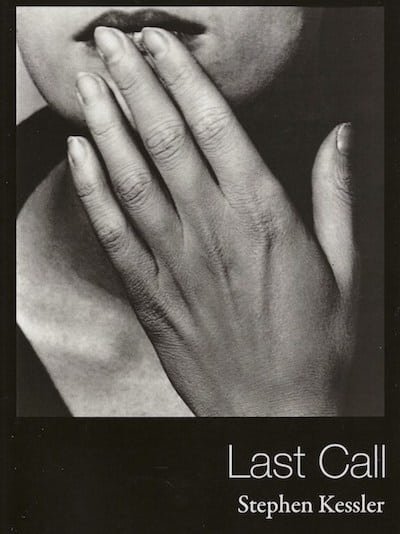

Last Call: Poems by Stephen Kessler

by Christina Waters | Nov 13, 2021 | Book |

Last Call: Poems by Stephen Kessler

Essayist, translator, pundit, and poet Stephen Kessler has been courting the muses for over 50 years. In his latest, largest, and 12th collection of poems, Last Call, Kessler’s elegant technique explores Santa Cruz, music, lost love, aging, irony, and pandemic epiphanies.

Q: Briefly tell me about how this collection of poems came about. What time period did they span? Where do they fit in your oeuvre?

My books tend to coincide with periods or “chapters” in my life. The poems in Last Call were written between January 2017, when I turned 70, and February of this year, when I received my first Covid vaccination. Those years happened to coincide with two terrible events in the personal and the public realm: the breakup of my marriage and the presidency of Donald Trump. So there was a lot of tough material to process, which accounts for the sense of grief and loss, especially in the first section of the book. “Bad Luck Charms.” My hope was and is through the alchemy of the language to turn all that hurt into something else—including ironic distance—the same way singing the blues can transform pain and heartbreak into something beautiful and consoling, maybe even funny.

Q: You’re known for the jazz syncopation of your poems, the way the lines stride and swing into each other. Do you read the work aloud as you write? or only afterward? How does it work?

I write by hand on paper (or with occasional exceptions on a manual typewriter) and try to let my hand do the thinking guided by the technical skills I’ve developed over about 65 years of practice, just as a jazz musician typically improvises spontaneously without reflection, letting the trained ear and fingers direct where the melody is going. I hear it in my head as it’s being written and try to just let it rip according to where the sounds of the language lead. Then I may read it to myself in a whisper to feel how it tastes as much as to hear how it sounds. If it feels more or less like natural speech but spring-loaded for torque from one line to the next, that’s the effect I’m hoping for. Sometimes it comes out right the first time and at other times it requires revision. But I always let it sit for a while to let it cool off so I can have a more objective look—and listen—at what I’ve written. If it’s not working, and I can’t fix it with a few adjustments, I tend to set it aside and move on to the next one, rather than try to save every poem by revising as extensively as I did when I was younger.

Q: I see more willingness to indulge in alliterative lines, in internal rhymes within the lines themselves. Were you consciously expanding your style in this collection?

Alliteration, internal rhyme, vowel rhyme and other prosodic devices have always served as my tools and techniques of composition, so I don’t see how this book is any different in that respect from most of my earlier work. But one’s style evolves, and I enjoy surprising myself from one line, one poem, and certainly one book to the next. At this stage of the game, I’m less concerned with writing a perfect poem (or a perfect book) than in letting the lines move to their own measure, so in that respect they may feel more indulgent or expansive in some way. But as I said, I’ve been reading and writing verse for so long—since childhood—that I feel enough confidence in my technical chops to let the poem take its own organic form. So there are lots of different shapes and sizes and styles of poems in this collection.

Q: Which muse pulled stronger, growing older or enduring quarantine?

Normally I’m accustomed to spending a lot of time at home alone with the writing, so the lockdowns weren’t all that inconvenient for me. But being increasingly old is something I don’t know if anyone ever gets used to, so the physical and psychic realities of entering “old age” (even though 70 is the new 50, and I’m reasonably healthy) play a much bigger part in the composition of this book—only the last year of which, maybe a dozen or 15 poems, was written during the pandemic.

Q: Can you reflect on the bittersweet irony of publishing your most ambitious late-career book, and calling it Last Call just when COVID shut down the world? As if the title were the leitmotif of the era itself.

The title came to me very early on, with the poem of that title, which I think was written about four years ago, so the pandemic had nothing to do with it. That poem was literally written at the bar of a local restaurant where the bartender was calling for any last orders before closing. It matched my gloomy mood of the moment and seemed fitting for the late-life themes I was wrestling with. Everyone asks if it’s meant as a valediction, and I think probably not, but then again, you never know. I certainly intend to keep writing, but that’s not entirely up to me. I expect the world will go on, with or without me.

Q: Much as complex recipes in fine cuisine, this work more than ever lays down opposing riffs—sweet and salty, joy and pain, darkness and clarity. A poet’s-eye view of the rhythm of existence itself?

In writing, as in cooking, I use whatever ingredients and seasonings are at hand. I definitely prefer a book—my own or anyone else’s—that moves through a range of themes and moods and motifs rather than repeats a formula over and over. Doesn’t everyone go through different rhythms of existence? Looking back over some 50 years of publishing, I feel as if I’ve consistently tried to respond as honestly as possible to the full range of my lived experience. I just hope I’ve gone deep enough that the poems resonate with the experience of others.

Q: You never draw attention to craft—form, composition, conscious/slant rhyming—in your work. Yet I have to admire the impeccable line breaks like some of these in “Last Call”:

trees crashing through

roofs, blackouts,

rivers rising and

spilling into living

rooms leaving a film

Does the spontaneous observation trump craft in your work? Or were these poems different in feel/form?

What you call “craft” I call technique, and it’s baked into the writing in a way that’s inseparable from imagination or observation, just as form and content in the best poems are seamlessly integrated. I learned the fundamentals when I was in elementary school by reading (for fun!) traditional English poetry (my family had a paperback copy of Palgrave’s Golden Treasury of Songs and Lyrical Poems) and writing imitations of rhymed and metered verse—usually just to entertain my friends. I wrote the lyrics to the class song for both grade school and high school graduations. I learned to write a poem for any occasion. Most of those efforts, when they weren’t intentionally funny, were no good as poetry except in a formal sense: they scanned metrically according to whatever form I was imitating, and they rhymed at the ends of the lines. So listening for rhythm and rhyme became habitual, and by the time, around 18 or 19, I started writing “free verse”—a misnomer because it demands even more formal control than fixed forms, requires that you create your own form on the blank page—these prosodic principles were ingrained in me. It took me many more years, decades even, to learn to deploy them effectively in composition, but by now I’ve been doing it for so long that the form the poem takes is second nature, and almost unconscious until I look and see what I’ve done. In the case of the title poem you quote from, the length of the lines was determined by the width of the notebook page I was writing on; the breaks just happened to work as written, so I didn’t mess with it. Other poems written in the same pocket notebook came out completely differently because I heard the breaks to fall in different places.

Q: Some poems in this collection are only a few words wide, forcing me to read downward (vertically) in a single gulp. Others stretch more words across the page, slowing down your voice and the reader’s intake. How do these decisions come to you?Funny, for me, short lines tend to slow a poem down, and long lines move more swiftly across the page. That just shows how we all read differently. As noted above, in some cases it’s the width of the page I’m writing on, or in the case of “Borges’s Belt,” it was the strip of paper I was typing on as the poem describes its own physical creation. “Paisley Yours” is in the voice of the model in the middle of a magazine page, and the narrow white space on either side of the image determined the long skinny shape of the poem as I typed it on my 1974 Adler manual portable. Others may start as prose in the first draft and once I see the whole thing I find where the breaks belong. And still others are composed originally as verse because the lines come to me one at a time and that’s the way I set them down. Most of these decisions make themselves according to how the composition unfolds. I don’t have any rational method, it’s a much more intuitive process based on the measure I hear in my head. I find the formal openness yet technical precision required of “free verse” to be as mysterious and unpredictable as how the poem’s images are imagined—usually by sonic association more than conscious choice. At best I feel like a medium, or an amanuensis to the muses, just taking dictation.

Q:Do you know when the words are good?

Usually—but not how. Sometimes in real time as they’re set down; at other times only later, from a more detached perspective. In some ways it’s easier to know when they’re not so good, when they’re clunky or prosaic or just “off” in some way. When the good ones are coming I’m too caught in the flow to really understand what’s happening, and when I see what I’ve done I can’t figure out how it happened. Composition as possession. I’ve learned to surrender to whatever it is that’s got hold of me, usually some kind of rhythmic riff, a few words strung together, a phrase unfolding according to its own melodic logic. And it feels good when the words are good—so I guess that’s how I know.

Q: Finally, an appreciation. “Discourse on Distraction” is a disarming piece of rumination, in which you move from the almost Platonic general down to the tangible specific. The last lines are among your finest, in which you clearly speak to the man within the poet:

there is no escaping the script you write with every step,

the strange rhymes ringing amid the dissonance,

the gifts, the great griefs,

the peripheral visions.

___________________________

Last Call, poems by Stephen Kessler

Black Widow Press, 200 pages, $19.95

Interview by Christina Waters

Zoom Forward reading Friday November 19, 5pm (Pacific time)

the ugly underbelly

by Christina Waters | Apr 12, 2017 | Book, Home |

Being an Author: the true story. . . Think twice before you fantasize about becoming an author. In the six months leading up to the publication of my book, Inside the Flame, and for the past five months afterwards, I have been enslaved to blog writing, Facebooking, and at least five other varieties of social media.

It’s taken me as long to set up the social media sites and incessant code-governed practices required of today’s publishing—as long as it took me to actually write the book.  Doing all of this is nothing short of hell, especially since most of us who write books simply wanted to write the damn thing. We didn’t want to become literary hookers selling ourselves and our ideas like so much virtual meat on any number of well-used digital platforms

Every morning I change my cover image on Facebook. Every morning I post an image, or an article, or a new mini-post about my book. On Facebook. And on LinkedIn. And on my website christinawaters.com, and on my Facebook Author site. Then I make sure I post something intriguing each week on Instagram, and on Goodreads. By Friday I’m exhausted, and still I cannot stop.

I need to create and line up at least three new posts for my Author page. Every. Week. Find images for them. And schedule them to go off like landmines all during the week.

Oh, did I forget to mention being held hostage by Constant Contact? Yes indeedy. You are not only required to create interesting content, as well as cheer-leaderesque self-promotional hypola, you’re required to package each week’s upbeat cry for attention (the weekly update) in an attractive manner. One that requires mining the internet for images. Cutting those images into the template’s preferred size. Writing excited emotionally-charged text, adding the appropriate links to places, people, and events tied into your product, i.e. The Book. Then the little announcement must be emailed out to potential, or alleged readers on your evolving email string.

And you must purchase this service using real money you may or may not actually have. Are you with me so far?

If I have a scheduled, in-person appearance, it gets worse. All the blogging, the social mediating, the posting, multiplies exponentially. Invite people. Tag people. Take pictures. Circulate the pictures. Post on friends’ sites, and when they post on mine, I immediately swoop in and thank them. “Excited!” I squeal (electronically). I feel like a needy and desperate performance artist enacting a public artwork for the benefit of a very few who have the time, the patience, and/or the inclination to dig deeper into what I’m up to than simply following my weekly food, wine, and art columns in GTWeekly.

People seem to love it when I’m irreverent, or highly opinionated, or critical of some public event which did not exactly deliver what I paid for.

People are less inclined to actually read an article, a thought-piece, or a critical essay in which I connect some intellectually or socially relevant dots and lead up to a reasoned (or at least well-illustrated) conclusion.

Here’s the deal: No one has any time. Everyone is overloaded. We are all overwhelmed with electronica, with digital obligations, with mindless FB happy talk and emoticon porno.

I’m exhausted. Worse. I’ve begun to turn on my own work.

Carmel Book Meet & Greet!

by Christina Waters | Apr 2, 2017 | Book, Home |

Carmel was always the spot my aunt favored for weekend getaways. “Let’s go window-shopping,” she would say, and away we went. Like a miniature English country village, Carmel seemed to offer an endless parade of intriguing pocket gardens, shops filled with color and dazzle, and small cafes for lingering in between excursions.

We would walk and walk, peek in windows, shop, eat, something sweet, and watch the people passing by. Such fun!

The village on the coast still holds its attraction, which is why I am thrilled to be making an appearance Saturday April 8th from 1-3pm at Pilgrim’s Way Bookstore, one of those authentic independent bookstores filled with exactly the books you want. My book Inside the Flame: the joy of treasuring what you already have will be there. And so will I and my friend Patrice Vecchione. Patrice is one of those creative writer/artists who never sleeps and is well known to legions of students in the Monterey Bay area. We’ll be there to talk about books, and I’ll be signing copies of my book Inside the Flame.

Exactly the sort of Carmel event my aunt would have loved.

Come join us! Purchase of my book Inside the Flame earns you a complimentary wine tasting at the nearby Windy Oaks Estates Tasting Room.

[I think you’ll be interested in my Artist Profile on game designer Elizabeth Swensen in the current GTWeekly!]

Meet & Greet Book Launch with author Christina Waters, PhD

Saturday — April 8th — 1-3pm

Pilgrim’s Way Bookstore & Secret Garden

Dolores between 5th & 6th, Carmel

Inside the Flame

by Christina Waters | Feb 24, 2016 | Book |

Watch this space!—you’ll find information and updates about my upcoming book,

Watch this space!—you’ll find information and updates about my upcoming book,

Inside the Flame: the joy of treasuring what you already have, launching November 2016 from Parallax Press.

(Weir on right, with his cinematographer Russell Boyd.)

(Weir on right, with his cinematographer Russell Boyd.)

(Bouley, with young extras in India.)

(Bouley with actor Colin Farrell in Weir’s The Way Back)

(Bouley with actor Colin Farrell in Weir’s The Way Back)