by Christina Waters | Jul 6, 2022 | Home |

From its first slowly undulating chords to the last sweeping thunder of destruction, Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelungen carries the listener along on an enveloping artistic journey like no other. The opera anticipated cinema and more than captured the composer’s declaration that the four-opera odyssey is indeed “a total work of art”—Gesamtkunstwerk.

It’s a tribute to the magic of Wagner’s vision that in my sixth journey through the 17+ hours of the Ring, I still felt the electrifying effect of the operas as if for the first time. Being swept away by the towering orchestration, the almost impossibly modern conceptualization and sound—so many passages argue for their dates being a hundred years into the future of their actual mid-19th century debut.

This is a work of art that never fails to fulfill expectations. And more. Last month I was treated to the view of the sunset over the Danube four evenings in a row. My experience two weeks ago with the four operas of the hero’s journey and the gods’ downfall unlocked even more secret passages of the great origin saga, not only of northern mythology but of the deep tissue of human psychology, the foibles, vanity, greed, desire, trickery, and love.

The music itself is the storyteller. The stalwart singers often seem to be there simply to punctuate the underlying text which, like the Rhine itself, roils and deepens as it winds through the many strands of fire and water, earth and heaven that ignite the uncanny masterpiece.

Tomasz Konieczny as Wotan: photo Nagy Attila/Müpa

Tomasz Konieczny as Wotan: photo Nagy Attila/Müpa

The story, a sweeping melange of Teutonic myth, Norse fairytale, and dreamscapes from the archaeology of human psychology, tells of the obsession of trolls, men, and gods for a ring of gold, a ring that brings limitless power to its owner. Changing hands over and over—and never by legitimate means—the ring has been forged by gold stolen from the Rhinemaidens, and the course of the operas takes us to the creation of Valhalla, home of Wotan the ruler and his family of gods.

The saga awaits a pure and fearless hero, Siegfried, who can win the power of the ring by slaying a dragon (it’s complicated). He wins the ring as well as the love of Wotan’s Valkure daughter Brunnhilde until greed overcomes his foes, and the gods, Valhalla, and our heroic lovers all go up in flames. And yes, the gold finally returns to the Rhine in the end, with music repeating the opera’s opening musical themes coming full circle in an ending that is both unspeakably tragic and emotionally satisfying.

The four operas unfold over more than 17 hours and in the best possible world there are singers on the stage capable of sustaining a spell throughout those hours. It is a tall order that few can deliver. The charismatic cast for last week’s Ring cycle at the Bela Bartok concert hall in Budapest frequently held the audience in thrall. Stamina, superhuman breath control, and in the case of the soprano singing Brunnhilde, many high Cs even after long stretches of non-stop singing. Many aspire to these roles in the absolute pinnacle of opera.

Nagy Attila/Müpa

Nagy Attila/Müpa

I went to Budapest for two reasons: Wagner, and Wotan as performed by the great Polish bass-baritone Tomasz Konieczny [here with Christian Franz as firegod Loge]. The part of the mercurial king of the gods is arguably the most interesting in a cast of brilliant and volatile characters, including scheming underworld denizens, comedic forest dwellers, jealous goddesses, giants, a dragon, starstruck lovers, and tribal warriors. Wotan—would-be Lord of the Ring—is consumed by the all-too-human desires for endless power and infinite romance. I heard Konieczny sing Wotan in Vienna a few years back and like others in that audience fell instantly under the spell of his brooding and finely calibrated interpretation. Konieczny is a fine actor, a splendid singer, and attractive enough to make you realize just why even the earth goddess herself would fall for him. Possibly the finest Wotan in opera today, Konieczny—in the formal attire—rivals Daniel Craig for tuxedo cred.

Dinner each evening during the second one-hour intermission.

Dinner each evening during the second one-hour intermission.

The semi-staged concept seen in the Müpa Wagner Days productions gave me a new perspective on the Ring. The architecturally brilliant hall is not an opera house. It is a concert hall. That means no proscenium stage, no wings, and no curtain. It is a stage that has been given a few bits of architecture, notably a central stairway leading up to a wide screen on which are projected various atmospheric videos, and around which characters can come and go to suggest changes of scene. The singers all were clad in black formal attire—tuxes for the men, gowns of varying descriptions for women. The orchestra pit was just in front and below the stage, about 20 feet from my raised side seat, a version of a box seat.

The effect of this minimalism was that the opera was immediate and intimate. No sets or built scenery got between the music and the audience. The singers became actual characters in the story, a Singspiel almost in bardic tradition, as much as acted out. In other words, there was nothing to get in the way of the glorious music (except for a troupe of dancers, whose movements echoed the sung story, to mostly distracting effect).

It was my sixth Ring, and with each viewing the story grows clearer and deepens. Wagner is very carefully and lovingly reconstructing the Creation myth of German identity. The story is everything, and it is given the greatest possible music as its vehicle.

Konieczny, a true Helden-baritone is a superb actor, delivering the emotional complexity of Wagner’s vision with expressive body language and vocal nuance. The powerful voice is capable of standing up to the composer’s dense instrumentation. And he can do it for many hours across the operas. As the frustrated god ensnared by his own traps, Konieczny illuminated the eternal truth of Wotan’s passions and regrets. He appears to consider, to negotiate, to weigh the dimensions of everything he’s saying and doing. And yet the singer has performed this role dozens and dozens of times. All the irony and folly, that the gods are only as great as their worshippers, and always as small as their own addictions. comes out clearly. Master as slave.

Konieczny, a true Helden-baritone is a superb actor, delivering the emotional complexity of Wagner’s vision with expressive body language and vocal nuance. The powerful voice is capable of standing up to the composer’s dense instrumentation. And he can do it for many hours across the operas. As the frustrated god ensnared by his own traps, Konieczny illuminated the eternal truth of Wotan’s passions and regrets. He appears to consider, to negotiate, to weigh the dimensions of everything he’s saying and doing. And yet the singer has performed this role dozens and dozens of times. All the irony and folly, that the gods are only as great as their worshippers, and always as small as their own addictions. comes out clearly. Master as slave.

The emotional pivot of the operas happens near the end of the second, and possibly best known of the four operas, Walküre. Angry at her disobedience, Wotan is forced to punish his beloved daughter Brunnhilde, the one who understands and knows him best, by casting her out of Valhalla. Utterly convincing in the heartbreak of a father forced to banish his best-loved daughter, Konieczny delivered indelible tenderness. Here is the beginning of the twilight of the gods, as Wotan’s fierce warrior daughter is suddenly plunged into mere womanhood, made mortal.

As the Brunnhilde for that single night, British soprano Allison Oakes stepped into a genuine star-is-born moment when the original singer, Irene Theorin, was forced to cancel due to illness. Believably vulnerable, defiant, and best of all in great voice she won over fellow singers and the audience as well. Konieczny graciously supported her performance, deferring to her in stage position and in emotional intensity. Tears filled my eyes during their final farewell embrace. It was a brilliant pairing of voices and intuitions and when they came out for a bow at the end of the opera, Konieczny and Oakes hugged each other and bounced up and down with sheer joy at the performance they’d just given.

Many wonderful singer/actors in definitive roles throughout the four operas. A splendid Fricka, much-cuckholded wife of Wotan, sung by Atala Schöck, Nadine Weissmann (singing via video-tech) as the earth goddess Erda, and a persuasive Sieglinde, sung by Karine Babajanyan.

The scheming troll Alberich was performed with delicious bravura by Jochen Schmeckenbecher, the substantial part of comedic villain Mime was sung by Cornel Frey, and the charming giants, by basso-profundos Fafner (Walter Fink) and Fasolt (Sorin Coliban) who were shadowed by enormous puppet surrogates who loomed over the stage while Wotan quibbled over giving the coveted ring in exchange for the captured goddess Freia (Lilla Horti).

But there were production issues, notably the very slick and steep staircase in the centerstage. It allowed performers to change vantage points for dramatic purposes, but it also caused frequent slipping, sliding, and in one case an actual tumble. The atmospheric video displays on the screen at the back of the stage were effective in creating a sense of changing mood and setting. A small company of extraordinarily limber and graceful dancers often arrived without any particular motivation, cluttering the stage just at climactic musical moments, frequently breaking the spell. Such a device, adding pop-up texture on an otherwise bare stage, is an innovative and often successful solution. As when the dancers writhe on the stage below the singers, acting as the trolls working in the goldmines deep below the earth. And there were two dancers dressed in red suits, who appeared frequently to help guide the gods up or down the Valhalla landscape, again, annoyingly.

Another issue: The seemingly tireless tenor Stefan Vinke gave his energetic all to the enormous role of Siegfried, the hero who knows no fear, yet incessant grinning and fist-bump gestures managed to take his character out of the innocent hero category straight into clueless good ole boy territory. He did manage the arduous love duet with Brunnhilde with all the high notes intact, less so during the long last opera. When forging the sword Nothung in the third opera, his resounding “ho ho ” passages were confident and compelling. Truly a helden-tenor delivery of the booming top notes.

Hirling Bálint/Mupa

Hirling Bálint/Mupa

And another: As the Brunnhilde of the final two operas, Catherine Foster was a visual curiosity, tugging on her too-tight spandex costume and holding her arms in the awkward chicken-about-to-strike pose. Eyes always on the conductor, her voice was often glorious, but more often she failed to arrive at the top notes in crucial passages. Even less convincing was Petra Lang, who I’d seen in Bayreuth as a seductive Ortrud in Lohengrin, and as a passable Brunnhilde in Vienna. Singing the Valkure Waltraute, arriving to persuade Brunnhilde to return the ring to the Rhinemaidens and end the downward spiral of emotions and violence, Lang preened and pouted as if giving a command recital. No tender pleading, all vibrato-tainted grandstanding.

As always with the Ring, it is the orchestra—passionately led by conductor Adam Fischer—who carried the evening. The enormous horn section, the tireless precision of the strings, the celestial shimmer of six extra harps positioned three on each side of the top balconies, the Hungarian Radio Symphony Orchestra was moved firmly through the four days of music by maestro Fischer. The conductor has said that the Ring “is the kind of intense journey that cannot be interrupted.” And it wasn’t. At other venues, these four operas take place over a longer stretch of time, with a day or two break in between the long hours of performance. Here at the Müpa production it was possible to stay completely engaged each day, without a break, until Valhalla’s flames are finally quenched in the waters of the river. Surely this is one reason why several of the large roles were performed by two different singers. Two Wotans, two Brunnhildes. It was arduous and yet unforgettable to stay within the magic of the unfolding story, night after night, until the stunning end.

One musicological note. At the end of the first opera, Das Rheingold, as Wotan leads his family of handsome gods and goddesses up to their shining new Valhalla, Wagner has scored a luscious bolero. The blatantly sensuous rhythm of this procession to the home of the gods implies success, security and triumph. Such bravura makes it all the more poignant when bit by bit the immortality, composure, and fortune of the gods crumbles. It is a huge fall, underscoring the hubris of trying to have it all, and the corruption that comes with the quest for power.

by Christina Waters | Jul 6, 2022 | Home |

In warm, humid, beautifully green Budapest, I stroll along the Danube before approaching 19th century interior of the lovely old Gerbeaud, a destination cafe and pastry shop in the heart of old town Budapest.

Here along with a juicy variety of mostly ladies who lunch, but the occasional Italian man, or table of German students with backpacks, I selected an opulent pastry from a display case of cakes, tortes, and strudels capable of inducing diabetes right on the spot. The interior, with its dark wood, chandeliers, and tall windows is straight out of Florence circa 1890.

The pastry looked like a Disney movie, but incredibly enough it was actually wonderful. Like a hyper-creamy cheesecake built on top of a disk of pastry crust with apricot puree embedded inside. Along with the world’s tiniest espresso, I ate almost the entire million calorie delight.

Nearby, along the pedestrian corridor with its herringbone and checkerboard walkways of cobblestones, were a handful of lively cafes including Anna Cafe, a place filled with locals and visitors from all over the world—mostly America, France, and Germany—all clamoring for beer, ice cream, and some of those slow-cooked Hungarian specialties.

I too succumbed to an irresistible Chicken Paprikish with galuszkaval….little noodlelike dumplings. The dish arrived steaming hot, utterly delicious. Homey chicken stew liberally perfumed with paprika, and the noodles were the ultimate comfort food. The temperature in the shade was at least 85 degrees so my lunch was consumed with a large bottle of mineral water. The couple to my right worked their way through enormous bowls of ice cream, sauced with chocolate and fruit, and topped with whipped cream. Bowls the size of children’s wading pools. They finished everything.

I too succumbed to an irresistible Chicken Paprikish with galuszkaval….little noodlelike dumplings. The dish arrived steaming hot, utterly delicious. Homey chicken stew liberally perfumed with paprika, and the noodles were the ultimate comfort food. The temperature in the shade was at least 85 degrees so my lunch was consumed with a large bottle of mineral water. The couple to my right worked their way through enormous bowls of ice cream, sauced with chocolate and fruit, and topped with whipped cream. Bowls the size of children’s wading pools. They finished everything.

On my first evening in Budapest—the only one in which I would not be sitting in a long opera—I went downstairs to my hotel restaurant, which happened to have a Michelin star. Costes Downtown is sleek, minimalist, and smartly run by young staffers who speak excellent English. My fellow diners were from France, Germany, and England. [English was the default language everywhere in Budapest. Good thing, since Hungarian is known for being among the most difficult languages in the world, second only to Finnish.]

I tell the hostess I can’t possibly consume the eight (8) courses of the prix fixe dinner, so she smartly consults with the kitchen and offers me the four course lunch menu instead. Eager to sample the non-Tokay Hungarian wines, I opt for the wine pairing to go with the meal.

The courses, all wonderful, begin with delightful amuses. A warm kumquat arrives filled with pureed kumquat. A granita of citrus and Campari comes topped with carrot foam. A baby green leaf is flash fried. The bread is so good I could cry. An oat-based ciabatta, it arrives with a fist full of soft French butter that has been oak-smoked and topped with (so help me) Hawaiian charcoal. The effect is of a hint of smoke and intensely mineral/salt finish. This is bread that can actually hold its own with my fresh memories of French baguettes.

The courses, all wonderful, begin with delightful amuses. A warm kumquat arrives filled with pureed kumquat. A granita of citrus and Campari comes topped with carrot foam. A baby green leaf is flash fried. The bread is so good I could cry. An oat-based ciabatta, it arrives with a fist full of soft French butter that has been oak-smoked and topped with (so help me) Hawaiian charcoal. The effect is of a hint of smoke and intensely mineral/salt finish. This is bread that can actually hold its own with my fresh memories of French baguettes.

Next comes a square of house cured salmon topped with the surprise of sliced green strawberries and a glaze of ponzu sauce. Flavors that are fabulous together, yet who does such a pairing? I’m beginning to sense the chef’s modus operandi. The first wine arrives, a single vineyard white with a slight effervescence, salt and stone in the beginning, a fresh finish. Every dish that arrives comes on a different kind of plate or platform, from a slice of agate, to a marble bowl, to glazed stoneware, to porcelain. Wonderful.

Another starter of grapefruit, with fresh tarragon on a shallow lake of pistachio cream is a surprise and a knock-out.

Another starter of grapefruit, with fresh tarragon on a shallow lake of pistachio cream is a surprise and a knock-out.

The second white wine has the sweet nose of botrytis, but a crisp finish to go with a dish of lightly cured rainbow trout with dashi and blackberries. The chef spent time in Vietnam and Tokyo, as well as in the kitchen of Ferran Adria, all of which inflects his tendency toward Asian accents.

The main course of aged Hungarian beef is served with a splendid cabernet franc offering ample tannins. A little salad on the side is topped with glistening salmon caviar and cornichons. The surrounding sauce is bright with citrus, chiles, sesame, truffle foam and roast potatoes.

The main course of aged Hungarian beef is served with a splendid cabernet franc offering ample tannins. A little salad on the side is topped with glistening salmon caviar and cornichons. The surrounding sauce is bright with citrus, chiles, sesame, truffle foam and roast potatoes.

Dessert is chocolate mousse with hazelnuts and a passionfruit caramel sauce. Dreamy is the word that comes to mind. After an espresso—why not live on the wild side?—I take a glass of Fernet Branca up to my room. And sleep very well.

Dessert is chocolate mousse with hazelnuts and a passionfruit caramel sauce. Dreamy is the word that comes to mind. After an espresso—why not live on the wild side?—I take a glass of Fernet Branca up to my room. And sleep very well.

by Christina Waters | Jul 6, 2022 | Home |

Parsifal: Twilight of a Production

Having traveled 5000 miles to dive into the Opera Bastille production of Wagner’s final opera, I was poised for a memorable experience. And while I certainly got one, it was mostly for the wrong reasons.

Here’s the short version.

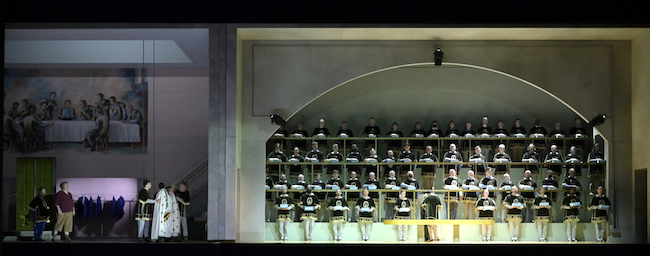

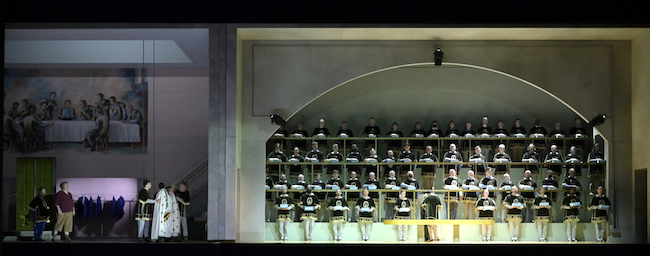

Conducted by Wagner veteran, Simone Young, the Paris Opera gave a fine reading of music so romantically breathtaking that it defines “sublime.” Excellent throughout, the orchestra managed to hold out against a mesmerizing yet ultimately destructive production, perpetrated by director Richard Jones. The elaborate set, moving on invisible tracks to reveal ever more chambers and levels, was clever, ludicrous, puzzling, and silly.

The costumes were blatantly ugly, and while we don’t always expect singers who are svelte, or who are also good actors, we could hope for more than the baggy shorts, backpacks, and sweatshirts most of the principals had to endure. Also terrible—save for the stalwart Kwangchul Youn as Gurnemanz, and Falk Struckmann as Klingsor—the singers had their eyes glued on the conductor for most of the performance.

photo: Vincent PONTET

The chorus was wonderful. And even though the music simply cannot be ruined, the production design tried its hardest to cut deeply into Wagner’s spiritual vision. Trashing the concept of Parsifal’s innocence overcoming magician Klingsor’s malevolent genetic engineering, the Act 2 Set of lusty flowermaidens jiggling fake boobs and buns non-stop, was tiresome. This four-year-old production felt distinctly dated.

Nothing this production threw at the audience did anything to illuminate new vistas, or unprobed corners of this complex work of art. The final act was inexcusably boring. Three people, standing around on a nearly bare stage, singing at each other (and none too well) for over an hour.

Now for the longer version.

Conductor Simone Young moved the Paris Opera orchestra smoothly through the depths of Wagner’s final opera, the entire ensemble firmly in her eloquent hands.

The underlying spirituality of the composer’s great music-drama “consecration” came through clearly, despite the visual antagonism of an agnostic setting and shallow visual interpretation.The point is made clearly by the great horn motifs and ascending chromatics of chord structure, the rising colors of the sound as if sunlight suddenly thrusts through the rose window of a great cathedral. Music and setting contradicting each other whenever possible.

As the opera moves us through an often incomprehensible maze of myths, metaphors, and magic, the composer summarizes his own repertoire, unafraid to quote his own work, to borrow from his own splendid musical themes.

While contemporary, even futuristic visual settings are often effective in reinforcing the romantic timelessness of the story, in the case of Richard Jones’ concept quite the opposite is true. The clever but overwrought transplantation of the story into future of cultish monasticism fail to move our understanding any further. The flower maidens as GMO-creations of exhaustingly explicit sexuality—less would have been more. The elision of sports cults and religious fanaticism, while perhaps persuasive, again didn’t illuminate the overall genius of this last work of the great master.

For that, we had the music itself.

Here’s the best place to focus on the complex set, which moved laterally to reveal ever more chambers, and in some scenes multiple levels. An arresting illustration of the opera’s mythic words: “here Time becomes Space.” From the study hall of what appears to be a cult devoted to “the Word,” the set moved the actors into austere chambers containing the bleeding Gail lord Amfortas and in a small bedroom upstairs, the dying founder of the Grail knights, Tintural. As the set continued to expand, it revealed a conference room crowned by a mural of a proto-Last Supper, and finally into a huge sports arena lined with row after row of cult followers (the mighty Paris Opera choir, flawlessly trained by choral director Ching-Lien Wu).

Calling lots of attention to itself, the set was alternately effective and silly, inspired and stupid. This production by Richard Jones feels smug about itself, the clever set as visual tour de force, with robotic cult members whose movements have been honed to within a goose step. And yet without the rapture implied by the chromatically mutating music, the entire production comes off as ironic and sterile.

The complete opposite of the semi-staged Ring I went on to see in Budapest, where minimal staging allowed the music and voices to cast their spells with emotional intimacy, the Paris Parsifal felt robotic, overwhelmed, and tired. Hopefully it will be retired for something fresh. Perhaps something that has more to do with the music, and less with the sort of fashionable revisioning that can completely undercut the musical ideas. The Frank Castorf Ring in 2013 comes to mind. Or the Sebastian Baumgarten Tannhäuser in which grotesque romping monsters obliterated some of the most gorgeous music ever composed.

Photo : Vincent PONTET

In warmup suits as if about to attend a sports contest—the Paris Open perhaps?—the old faithful knight of the Grail, Gurnemanz, was given stalwart voice by Parsifal veteran Kwangchul Youn. I’d heard him in the 2014 Bayreuth production in the same role, and his resounding and tireless musicality seemed not to have aged. As the wounded Grail lord Amfortas, Iain Paterson looked and sounded exhausted. As the pure fool, Parsifal, Simon O’Neill relied on almost non-stop eye contact with conductor Young as if uncertain what his next lines should be. The mercurial time-traveling witch Kundry, dressed in hipster backpack and sweatshirt sung by Russian mezzo-soprano Marina Prudenskaya, was neither believable nor vocally engaging. By the end of the opera, she had devolved from temptress to penitent, and then finally as best buddy to the hero with whom she sauntered off-stage hand-in-hand. In Wagner’s original version, Parsifal absolves her wickedness and she gratefully swoons and dies.

The last act, incomprehensibly sung against a bare stage, is inexcusably boring. Why have the newly repentant witch Kundry, and the newly awakened Parsifal, explain their realizations in a completely empty space? Vocal precision and color might have helped. But these were alas also missing.

Would that this bewildering yet majestic music had been sung by brilliant voices. As it was, the June 6 performance left me longing to have heard the 2018 debut version of this production, with the acting genius Peter Mattei as Amfortas, heldentenor Andreas Shager as Parsifal, and the rich and adroit mezzo of Anja Kampe as Kundry. The veteran Wagnerian Falk Struckmann, as the malevolent magician Klingsor, announced through a spokesman at the start of the opera that he was not in his best form that night. My heart almost stopped. I’d been a fan since I saw him as Hagen in the Vienna Ring five years ago. A savvy actor, Struckmann performed nonetheless and even in less than perfect form he sounded better than most of the others on that stage.

The costume designer owes an apology to singers and audience Baggy clothing on Parsifal, fussy and dowdy costumes on Kundry, woefully malfunctioning fake blood on the robes of Amfortas, and the hilarious X-rated gyrations of the genetically engineered maize maidens made this Parsifal a pleasure only if you closed your eyes.

The ascending fifths of the Dresden Amen still worked their redemptive magic, and while this production makes almost nothing of the spiritual thrust of this opera, the splendid orchestra rose to the occasion. It made sense of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s confession that while he loathed the Christian theme underlying Parsifal, he had to admit the music was sublime. Sublime and worth the five hours and 5000 miles I’d traveled to enjoy.

Orchestre de l’Opéra national de Paris

by Christina Waters | Jul 6, 2022 | Home |

I’d waited for almost three years to get on a plane headed for Europe. And Paris did not disappoint. Balmy summer weather, baguettes as good as my memories, and a few days to kill roaming the city, and some great museums before my night at the opera—Parsifal—arrived.

The light rain falling as we drove into the city from Charles de Gaulle announced that I wasn’t in California anymore. Warm temperatures, day and night, noticeble humidity plus the long days of summer—sunset not until 10pm—felt especially welcoming. From my embarrassingly posh hotel across the street from the Louvre, I was able to explore a few bistros, shops, and of course the reassuring sight of Notre Dame, still splendid even surrounded by cranes and fencing.

One dinner at Paul Bocuse’s Hotel Louvre Restaurant, provided me with an impeccable Scottish salmon on a bed of potatoes, giant capers, and hazelnuts. Paired with the sort of bread that dreams are made of, and a glass of crisp Chablis, it answered a craving that had built up for several years of quarantine.

Next morning, reserved ticket in hand (or rather on my phone) I was ushered into a very short line (three people!) into the vastness of the Louvre. Avoiding the crowded line encircling the Mona Lisa, I instead re-visited a few of my favorite paintings, including a Mantegna that might have been painted yesterday, the miraculous Virgin of the Rocks, and rediscovered the genius of Jean-Louis David.

Next morning, reserved ticket in hand (or rather on my phone) I was ushered into a very short line (three people!) into the vastness of the Louvre. Avoiding the crowded line encircling the Mona Lisa, I instead re-visited a few of my favorite paintings, including a Mantegna that might have been painted yesterday, the miraculous Virgin of the Rocks, and rediscovered the genius of Jean-Louis David.

I devoured as much as I could before visual saturation set in and it was time to head up the street to Bistrot Victoires for a delicious duck confit with perfect potatoes and a glass of Côtes du Rhône.

I devoured as much as I could before visual saturation set in and it was time to head up the street to Bistrot Victoires for a delicious duck confit with perfect potatoes and a glass of Côtes du Rhône.

Followed by an espresso, the lunch confirmed my belief in Paris as a city of high culinary standards.

Followed by an espresso, the lunch confirmed my belief in Paris as a city of high culinary standards.

Next day, I sprinted across the Pont du Carousel to the Musée d’Orsay and a mini-orgy of 19th and 20th century artwork, distinguished by new and old Manets, a few choice van Goghs, and an array of gleaming Art Nouveau furniture, rugs, and candelabra.

Again, I tried to make sure I left before eye-stupor set in. I strolled up to the St. Germain neighborhood, and had an espresso at Les Deux Magots in honor of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir who often spent time smoking, drinking, and writing at this very cafe.

That evening, I walked across the river again to the exquisite Gothic jewelbox that is Saint Chapelle, built by St. Louis to house his splinter of the True Cross, and enjoyed the rare experience of an intimate concert of piano music by the heroic performer Vanessa Wagner, a woman with Bronzino arms and complete command of her instrument.

That evening, I walked across the river again to the exquisite Gothic jewelbox that is Saint Chapelle, built by St. Louis to house his splinter of the True Cross, and enjoyed the rare experience of an intimate concert of piano music by the heroic performer Vanessa Wagner, a woman with Bronzino arms and complete command of her instrument.

Only two hundred seats in the tiny upper sanctuary, still light enough at 8pm for sun to illuminate the incredible stained glass, as we listened to Mozart, Rachmaninoff, and Debussy. Acoustics as impeccable as the interior itself.

Only two hundred seats in the tiny upper sanctuary, still light enough at 8pm for sun to illuminate the incredible stained glass, as we listened to Mozart, Rachmaninoff, and Debussy. Acoustics as impeccable as the interior itself.

I sat outside on the patio of my hotel Palais Royal, with a Campari spritz, and enjoyed the feel of the soft heavy air on my face and arms. Parisians are a hundred times more diverse than we are in California, and the procession of colors and costumes, fashions and follies was almost as delicious as the cuisine.

The next evening was my night at the opera, so I enjoyed a Croque Monsieur and pommes frites at the nearby Cafe Blanc before heading out to the Opera Bastille, where I would consume only a glass of champagne and a ham and cheese sandwich during the next five hours and 15 minutes. [see my account of the opera itself in an adjoining post]

My last day in Paris I wandered through the renovated Art Nouveau interior of the enormous upscale Samaritaine department store. Then it was back to my neighborhood to the 2-star Michelin restaurant Palais Royal, where I had a long-awaited lunch reservation. Three courses, prix fixe, plus a glass of the kind of Bordeaux that makes you want to rob a bank.

Palais Royal and the handiwork of chef Philip Chronopoulos.

Armed with a pedigree that has taken him to London, Paris, and soon Venice, this chef sets an inventive tone. The room was simple, perfect, not fussy. The very young staff spoke English well, and unlike Parisian dining of yore, they smiled and made each diner feel comfortable—from the table filled with expense account businessmen to me, a solo diner splurging on what would be a memorable succession of gorgeous dishes.

The initial amuses dishes included a single deep-fried pastry pillow filled with a warm quail egg yolk. A little pastry boat filled with fresh pea puree, topped with a tangle of mâche and parmesan. A pretty salad of warm grapes and tiny beets arrived topped with a scoop of creamy feta in a pool of sweet and salty broth. And an incredible cheese straw (much more elegant than that) but essentially a finger of crisp cheese filled with veloté of foie gras—it was one of the best things I’ve ever tasted.[see below]

The initial amuses dishes included a single deep-fried pastry pillow filled with a warm quail egg yolk. A little pastry boat filled with fresh pea puree, topped with a tangle of mâche and parmesan. A pretty salad of warm grapes and tiny beets arrived topped with a scoop of creamy feta in a pool of sweet and salty broth. And an incredible cheese straw (much more elegant than that) but essentially a finger of crisp cheese filled with veloté of foie gras—it was one of the best things I’ve ever tasted.[see below]

And a miniature brioche topped with micro-zest of lemon. Plus two breads, arriving with a bowl of olive oil and another bowl of aromatic oregano. One flavor is intended to enhance its partner, you combine them as you like.

And a miniature brioche topped with micro-zest of lemon. Plus two breads, arriving with a bowl of olive oil and another bowl of aromatic oregano. One flavor is intended to enhance its partner, you combine them as you like.

Then came a plate of gamba, a large prawn, sided by two basil-tinged green gnocchi draped with calamari crudo, plus a flash fried zucchini flower, on a little hill of broccolini. The gnocchi each sat on a brilliant green sauce of basil. This dish justified the entire trip to Paris.

Then came a plate of gamba, a large prawn, sided by two basil-tinged green gnocchi draped with calamari crudo, plus a flash fried zucchini flower, on a little hill of broccolini. The gnocchi each sat on a brilliant green sauce of basil. This dish justified the entire trip to Paris.

All flavors were robust yet unmuddied. Each ingredient made sense of the others, showing the chef’s intuitive understanding of how the dish would unfold as a process, rather than single creation of flavors combined in the kitchen. The center of the meal was a plate of duck encircled by warm cherries and a cherry mustard balsamic reduction. Adorned with tiny onion flowers. Yes it was terrific. But not as terrific as my dessert.

Arriving in two dishes was what amounted to a deconstructed tiramisu. As with all of this chef’s dishes, the dessert was intended to be enjoyed as a sequence, or layering of flavors.

Arriving in two dishes was what amounted to a deconstructed tiramisu. As with all of this chef’s dishes, the dessert was intended to be enjoyed as a sequence, or layering of flavors.

Mascarpone ice cream in one dish, candied orange peel on the side, and a warm baba drenched in rum on a crust of coffee nibs. Creme Chantilly on top was dusted with a veil of cacao and unidentifiable spices. I ate every bite. Finished with an espresso.

Mascarpone ice cream in one dish, candied orange peel on the side, and a warm baba drenched in rum on a crust of coffee nibs. Creme Chantilly on top was dusted with a veil of cacao and unidentifiable spices. I ate every bite. Finished with an espresso.

Tomasz Konieczny as Wotan: photo Nagy Attila/Müpa

Tomasz Konieczny as Wotan: photo Nagy Attila/Müpa

Nagy Attila/Müpa

Nagy Attila/Müpa Dinner each evening during the second one-hour intermission.

Dinner each evening during the second one-hour intermission. Konieczny, a true Helden-baritone is a superb actor, delivering the emotional complexity of Wagner’s vision with expressive body language and vocal nuance. The powerful voice is capable of standing up to the composer’s dense instrumentation. And he can do it for many hours across the operas. As the frustrated god ensnared by his own traps, Konieczny illuminated the eternal truth of Wotan’s passions and regrets. He appears to consider, to negotiate, to weigh the dimensions of everything he’s saying and doing. And yet the singer has performed this role dozens and dozens of times. All the irony and folly, that the gods are only as great as their worshippers, and always as small as their own addictions. comes out clearly. Master as slave.

Konieczny, a true Helden-baritone is a superb actor, delivering the emotional complexity of Wagner’s vision with expressive body language and vocal nuance. The powerful voice is capable of standing up to the composer’s dense instrumentation. And he can do it for many hours across the operas. As the frustrated god ensnared by his own traps, Konieczny illuminated the eternal truth of Wotan’s passions and regrets. He appears to consider, to negotiate, to weigh the dimensions of everything he’s saying and doing. And yet the singer has performed this role dozens and dozens of times. All the irony and folly, that the gods are only as great as their worshippers, and always as small as their own addictions. comes out clearly. Master as slave. Hirling Bálint/Mupa

Hirling Bálint/Mupa

I too succumbed to an irresistible Chicken Paprikish with galuszkaval….little noodlelike dumplings. The dish arrived steaming hot, utterly delicious. Homey chicken stew liberally perfumed with paprika, and the noodles were the ultimate comfort food. The temperature in the shade was at least 85 degrees so my lunch was consumed with a large bottle of mineral water. The couple to my right worked their way through enormous bowls of ice cream, sauced with chocolate and fruit, and topped with whipped cream. Bowls the size of children’s wading pools. They finished everything.

I too succumbed to an irresistible Chicken Paprikish with galuszkaval….little noodlelike dumplings. The dish arrived steaming hot, utterly delicious. Homey chicken stew liberally perfumed with paprika, and the noodles were the ultimate comfort food. The temperature in the shade was at least 85 degrees so my lunch was consumed with a large bottle of mineral water. The couple to my right worked their way through enormous bowls of ice cream, sauced with chocolate and fruit, and topped with whipped cream. Bowls the size of children’s wading pools. They finished everything. The courses, all wonderful, begin with delightful amuses. A warm kumquat arrives filled with pureed kumquat. A granita of citrus and Campari comes topped with carrot foam. A baby green leaf is flash fried. The bread is so good I could cry. An oat-based ciabatta, it arrives with a fist full of soft French butter that has been oak-smoked and topped with (so help me) Hawaiian charcoal. The effect is of a hint of smoke and intensely mineral/salt finish. This is bread that can actually hold its own with my fresh memories of French baguettes.

The courses, all wonderful, begin with delightful amuses. A warm kumquat arrives filled with pureed kumquat. A granita of citrus and Campari comes topped with carrot foam. A baby green leaf is flash fried. The bread is so good I could cry. An oat-based ciabatta, it arrives with a fist full of soft French butter that has been oak-smoked and topped with (so help me) Hawaiian charcoal. The effect is of a hint of smoke and intensely mineral/salt finish. This is bread that can actually hold its own with my fresh memories of French baguettes.

Another starter of grapefruit, with fresh tarragon on a shallow lake of pistachio cream is a surprise and a knock-out.

Another starter of grapefruit, with fresh tarragon on a shallow lake of pistachio cream is a surprise and a knock-out. The main course of aged Hungarian beef is served with a splendid cabernet franc offering ample tannins. A little salad on the side is topped with glistening salmon caviar and cornichons. The surrounding sauce is bright with citrus, chiles, sesame, truffle foam and roast potatoes.

The main course of aged Hungarian beef is served with a splendid cabernet franc offering ample tannins. A little salad on the side is topped with glistening salmon caviar and cornichons. The surrounding sauce is bright with citrus, chiles, sesame, truffle foam and roast potatoes. Dessert is chocolate mousse with hazelnuts and a passionfruit caramel sauce. Dreamy is the word that comes to mind. After an espresso—why not live on the wild side?—I take a glass of Fernet Branca up to my room. And sleep very well.

Dessert is chocolate mousse with hazelnuts and a passionfruit caramel sauce. Dreamy is the word that comes to mind. After an espresso—why not live on the wild side?—I take a glass of Fernet Branca up to my room. And sleep very well.

Next morning, reserved ticket in hand (or rather on my phone) I was ushered into a very short line (three people!) into the vastness of the Louvre. Avoiding the crowded line encircling the Mona Lisa, I instead re-visited a few of my favorite paintings, including a Mantegna that might have been painted yesterday, the miraculous Virgin of the Rocks, and rediscovered the genius of Jean-Louis David.

Next morning, reserved ticket in hand (or rather on my phone) I was ushered into a very short line (three people!) into the vastness of the Louvre. Avoiding the crowded line encircling the Mona Lisa, I instead re-visited a few of my favorite paintings, including a Mantegna that might have been painted yesterday, the miraculous Virgin of the Rocks, and rediscovered the genius of Jean-Louis David. I devoured as much as I could before visual saturation set in and it was time to head up the street to Bistrot Victoires for a delicious duck confit with perfect potatoes and a glass of Côtes du Rhône.

I devoured as much as I could before visual saturation set in and it was time to head up the street to Bistrot Victoires for a delicious duck confit with perfect potatoes and a glass of Côtes du Rhône. Followed by an espresso, the lunch confirmed my belief in Paris as a city of high culinary standards.

Followed by an espresso, the lunch confirmed my belief in Paris as a city of high culinary standards.

That evening, I walked across the river again to the exquisite Gothic jewelbox that is Saint Chapelle, built by St. Louis to house his splinter of the True Cross, and enjoyed the rare experience of an intimate concert of piano music by the heroic performer Vanessa Wagner, a woman with Bronzino arms and complete command of her instrument.

That evening, I walked across the river again to the exquisite Gothic jewelbox that is Saint Chapelle, built by St. Louis to house his splinter of the True Cross, and enjoyed the rare experience of an intimate concert of piano music by the heroic performer Vanessa Wagner, a woman with Bronzino arms and complete command of her instrument. Only two hundred seats in the tiny upper sanctuary, still light enough at 8pm for sun to illuminate the incredible stained glass, as we listened to Mozart, Rachmaninoff, and Debussy. Acoustics as impeccable as the interior itself.

Only two hundred seats in the tiny upper sanctuary, still light enough at 8pm for sun to illuminate the incredible stained glass, as we listened to Mozart, Rachmaninoff, and Debussy. Acoustics as impeccable as the interior itself.

The initial amuses dishes included a single deep-fried pastry pillow filled with a warm quail egg yolk. A little pastry boat filled with fresh pea puree, topped with a tangle of mâche and parmesan. A pretty salad of warm grapes and tiny beets arrived topped with a scoop of creamy feta in a pool of sweet and salty broth. And an incredible cheese straw (much more elegant than that) but essentially a finger of crisp cheese filled with veloté of foie gras—it was one of the best things I’ve ever tasted.[see below]

The initial amuses dishes included a single deep-fried pastry pillow filled with a warm quail egg yolk. A little pastry boat filled with fresh pea puree, topped with a tangle of mâche and parmesan. A pretty salad of warm grapes and tiny beets arrived topped with a scoop of creamy feta in a pool of sweet and salty broth. And an incredible cheese straw (much more elegant than that) but essentially a finger of crisp cheese filled with veloté of foie gras—it was one of the best things I’ve ever tasted.[see below] And a miniature brioche topped with micro-zest of lemon. Plus two breads, arriving with a bowl of olive oil and another bowl of aromatic oregano. One flavor is intended to enhance its partner, you combine them as you like.

And a miniature brioche topped with micro-zest of lemon. Plus two breads, arriving with a bowl of olive oil and another bowl of aromatic oregano. One flavor is intended to enhance its partner, you combine them as you like. Then came a plate of gamba, a large prawn, sided by two basil-tinged green gnocchi draped with calamari crudo, plus a flash fried zucchini flower, on a little hill of broccolini. The gnocchi each sat on a brilliant green sauce of basil. This dish justified the entire trip to Paris.

Then came a plate of gamba, a large prawn, sided by two basil-tinged green gnocchi draped with calamari crudo, plus a flash fried zucchini flower, on a little hill of broccolini. The gnocchi each sat on a brilliant green sauce of basil. This dish justified the entire trip to Paris. Arriving in two dishes was what amounted to a deconstructed tiramisu. As with all of this chef’s dishes, the dessert was intended to be enjoyed as a sequence, or layering of flavors.

Arriving in two dishes was what amounted to a deconstructed tiramisu. As with all of this chef’s dishes, the dessert was intended to be enjoyed as a sequence, or layering of flavors. Mascarpone ice cream in one dish, candied orange peel on the side, and a warm baba drenched in rum on a crust of coffee nibs. Creme Chantilly on top was dusted with a veil of cacao and unidentifiable spices. I ate every bite. Finished with an espresso.

Mascarpone ice cream in one dish, candied orange peel on the side, and a warm baba drenched in rum on a crust of coffee nibs. Creme Chantilly on top was dusted with a veil of cacao and unidentifiable spices. I ate every bite. Finished with an espresso.