by Christina Waters | Sep 25, 2017 | Home |

Anyone who has seen opera sets by David Hockney remains fairly breathless for days on end. Sometimes years. Rarely has a practicing artist shown such a keen understanding of, and fascination with the playful possibilities of visual storytelling. His sets summon the unconscious foremost by an uncanny fluency with primary colors. Hockney owns red, as the audience for the SF Opera season opener Turandot witnessed with delight last week.

As the curtain came up on the first act of Puccini’s fairytale of old Peking (an Orientalist interpretation of a place that never was)—in which an icy princess Turandot contends with the unknown suitor who will attempt to successfully answer her three riddles—the entire opera house gasped. However many times you’ve feasted on Hockney’s spectral intensity (I’ve been lucky enough to have seen his scenic design in Tristan und Isolde and The Magic Flute) you’re simply not prepared to be so overwhelmed by the sheer saturation of hue.

Now add to that the artist’s set design which seems to occur in at least five spatial dimensions at once, bending and curving rooftops, castle walls, and steep zig-zag stairways so that the stage itself appears to have been pushed into some new, larger-than-life domain.

Hockney knows how the spatial bending, severing, and re-configuring of architecture can form the exact thematic match for the story—in this case a genuine, if unsettling fairytale. [There must be a law somewhere that all opera plots verge on the ridiculous]. Add to all of this Puccini’s dramatically soaring music, alternately romantic and rugged, and you have a masterwork that by all accounts forms the bedrock of entry-level opera. The extraordinary costumes by Ian Falconer, in which the designer’s understanding of design and color contrast is relentless, provided opera costumes that essentially set the bar for the fantasy design universe. Both scenic and costume design are simply in a World Heritage class of their own. Appealing equally to 8-year-olds and 80-year-olds, this Turandot is a brisk 2 hour and 45 minute feast for all of the senses.

First a digression to mention a few details of SF Opera innovation.

Possibly in an effort to open up the opera experience to include new, and younger audiences, this season marks a tentative “experiment” with allowing purchased drinks to be brought into the theater (in plastic cups with tight-fitting lids). I saw only a few such instances last week, e.g. a middle-aged woman had brought her sauvignon blanc in with her and was discreetly sipping it during the second act. The sky did not fall.

Also, there was something else new—the curtain remained up for a full 20 minutes during the first intermission so that audience could watch some of the fascinating work of moving, altering, and rearranging the key elements of the set. As stage crew—there are 57 working on this production—began altering the stage elements, two production directors explained some of the behind-the-scenes operations to the audience, most of whom stayed to watch. For some of us, this breaks the spell, but for others—who enjoy this sort of backstage revelation seen in the Metropolitan Opera HD simulcasts—it provided an invitation to learn more, and want to see more of live opera.

Also, there was something else new—the curtain remained up for a full 20 minutes during the first intermission so that audience could watch some of the fascinating work of moving, altering, and rearranging the key elements of the set. As stage crew—there are 57 working on this production—began altering the stage elements, two production directors explained some of the behind-the-scenes operations to the audience, most of whom stayed to watch. For some of us, this breaks the spell, but for others—who enjoy this sort of backstage revelation seen in the Metropolitan Opera HD simulcasts—it provided an invitation to learn more, and want to see more of live opera.

Another positive note: the opera house audience appeared to be of a much more mixed demographic, lots of young couples, entire families, and others who broke through the cliché of the white-haired opera-goer. We were overjoyed to see a younger crowd deciding to invest in the magic of live performance. Fingers crossed that this is a trend. [Image below displays Falconer’s playful color choices, pushing primary colors as far as they can go, and then tossing in a splash of purple for added eye candy!]

The power of the San Francisco Opera’s orchestra and chorus brilliantly moved the storytelling toward its several pinnacle arias, including the universally appealing “Nessun dorma” that launched many a tenor’s career. In the September 2017 performances, Brian Jagde sang the heroic suitor, determined to win the hand of the beautiful princess, no matter the sacrifice.

Here is the plum tenor role in all of Puccini (rivalling that of Cavaradossi in Tosca ), and when that moment came in the second act, and the familiar strains of the aria begin, the electricity in the crowd was palpable. Imagine the thrill, the sense of artistic serendipity, to be that tenor, at that moment, on the verge of performing such an iconic line of music. And Jagde was more than up to it. For which the audience unleashed a torrent of cheers and bravos.

While the gorgeous Martina Serafin looked every inch an imperious princess—imagined by Puccini as an imperial icon of ice and fire—she, much as Nina Stemme in last year’s Met production—had difficulty, especially in the impossibly high and relentess second act aria— her voice struggling with a distracting vibrato as she attempted to maintain the difficult passages. While she regained her vocal beauty in the final scenes (except when she utterly missed the final highest pitches), she seemed to lack the clarity and unforced beauty of soprano Toni Marie Palmertree, who as the luckless Liu was given much the better music to sing. The irony, for me, was that I had come to this particular performance of Turandot specifically to hear Serafin, whom I’d heard as a fabulous Tosca (opposite no less than Jonas Kaufmann) in Vienna in May.

While the gorgeous Martina Serafin looked every inch an imperious princess—imagined by Puccini as an imperial icon of ice and fire—she, much as Nina Stemme in last year’s Met production—had difficulty, especially in the impossibly high and relentess second act aria— her voice struggling with a distracting vibrato as she attempted to maintain the difficult passages. While she regained her vocal beauty in the final scenes (except when she utterly missed the final highest pitches), she seemed to lack the clarity and unforced beauty of soprano Toni Marie Palmertree, who as the luckless Liu was given much the better music to sing. The irony, for me, was that I had come to this particular performance of Turandot specifically to hear Serafin, whom I’d heard as a fabulous Tosca (opposite no less than Jonas Kaufmann) in Vienna in May.

It occurs to me that very likely no soprano can reasonably manage the vocal part of Turandot, and that it’s likely the composer’s fault, writing an all-but-impossible tessitura for this character either out of ignorance (hardly possible) or mischief (?). In other words, the relentless landscape of very high passages might not be singable. Period.

Turandot—the last, and partially unfinished opera that Giacomo Puccini wrote—premiered in Milan in 1926. It was performed the following year at San Francisco, where it has been revived four more times—this year in honor of David Hockney’s 80th birthday, an artist who is obviously having a lot of fun being alive.

Being There

by Christina Waters | Aug 7, 2017 | Home |

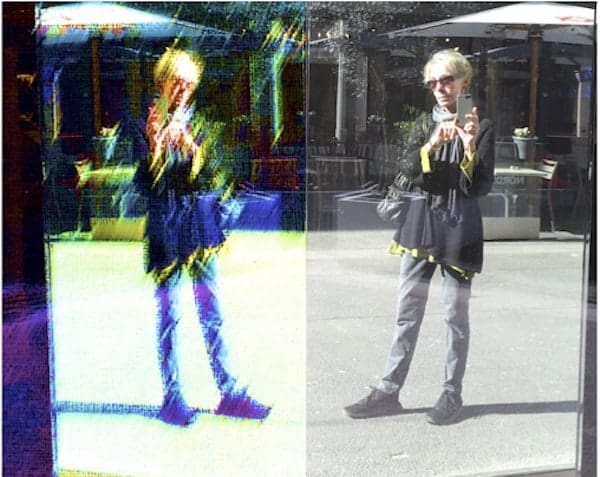

Have we lost contact with the tangible world? Look around. What do you see? Screens! Information gleaned through hand-held electronic devices. Through those screens we love to look at animals, our friends, mouth-watering foods, faraway landmarks, natural wonders.

What about going out and seeing/touching real live animals? Having coffee with our friends—face to face? Or hiking up to the top of Half Dome….using our own bodies to do the work?

The late playwright Sam Shepard had the same idea:

“What’s most frightening to me right now is this estrangement from life. People and things are becoming more and more removed from the actual. We are becoming more and more removed from the earth to the point that people just don’t know themselves or each other or anything.â€

Don’t just look it up on the Internet—make that recipe you love. Travel to see (and touch, and walk into) an old cathedral, remote village, vibrant marketplace.

Just don’t sit there and think that your iPhone’s app is a real communication link with what Shepard called “the actual.” Go outside and inhale deeply. Reality cannot be digitized.

Bill Viola in Florence

by Christina Waters | Jun 13, 2017 | Art, Home, Travel |

Here was a long-awaited experience—the chance to finally see the great Pontormo Visitation along with Bill Viola‘s haunting video response made five hundred years later. There in a single darkened room was the newly-restored Mannerist painting portraying the moment when Mary reveals to her cousin Elizabeth that she is pregnant. All the mystery and innuedo, the pungent psychological drama of what might have transpired is captured in their complex gaze, the swirling folds of the gowns, the torque of the bodies as they touch and yet turn away. Pontormo’s use of a single model for two of the figures adds a sparkle of surrealism to the moment. Mary’s mother Anne watches on, and an angel—also a witness—looks directly at us, viewers across the centuries.

On the adjacent wall, Viola’s larger-than-lifesize figures strain against time and space in hyper slow motion, re-imagining the meeting (the piece is called The Greeting) among Mary, Elizabeth, and a third woman. Gracefully surging skirts, arms reaching out, hands about to clasp, faces registering surprise, delight, and puzzlement, Viola’s work—which takes time to unfold— forces us deep into and beneath the minds of his subjects.

On the adjacent wall, Viola’s larger-than-lifesize figures strain against time and space in hyper slow motion, re-imagining the meeting (the piece is called The Greeting) among Mary, Elizabeth, and a third woman. Gracefully surging skirts, arms reaching out, hands about to clasp, faces registering surprise, delight, and puzzlement, Viola’s work—which takes time to unfold— forces us deep into and beneath the minds of his subjects.

The slowed-down movements and gestures cast digital congianti onto the image painted by Bronzino’s teacher in the early 16th century. Movement inflects stillness with layers of temporal depth. Absolutely stunning. Viola’s forensic probing of an emotion-drenched moment retrieves fresh sensations we can almost taste.

The slowed-down movements and gestures cast digital congianti onto the image painted by Bronzino’s teacher in the early 16th century. Movement inflects stillness with layers of temporal depth. Absolutely stunning. Viola’s forensic probing of an emotion-drenched moment retrieves fresh sensations we can almost taste.

The Pontormo is triumphant, its colors brilliant as if freshly painted. A commanding palette of draped robes challenges the crimson dress worn Viola’s Mary, the magenta shawl of Elizabeth.The two works now share a secret, at once timeless and yet produced across and through time; they murmur of the same epic event. They are in league with each other. Sono insieme.

The Pontormo is triumphant, its colors brilliant as if freshly painted. A commanding palette of draped robes challenges the crimson dress worn Viola’s Mary, the magenta shawl of Elizabeth.The two works now share a secret, at once timeless and yet produced across and through time; they murmur of the same epic event. They are in league with each other. Sono insieme.

I’ve taught some of the ideas and work of video artist Bill Viola in many of my courses over the past 15 years. And the more I reflect on his comments about his work, how it came into fruition, and the various influences upon them, the more my bond with his output deepens.

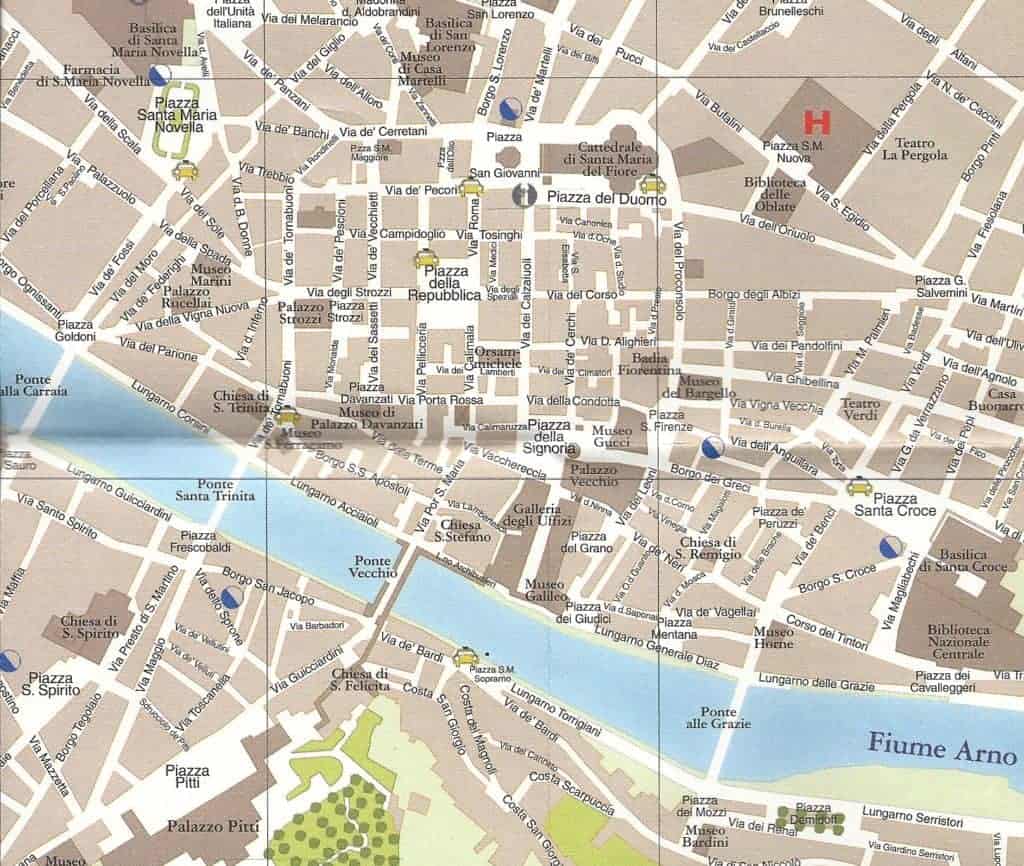

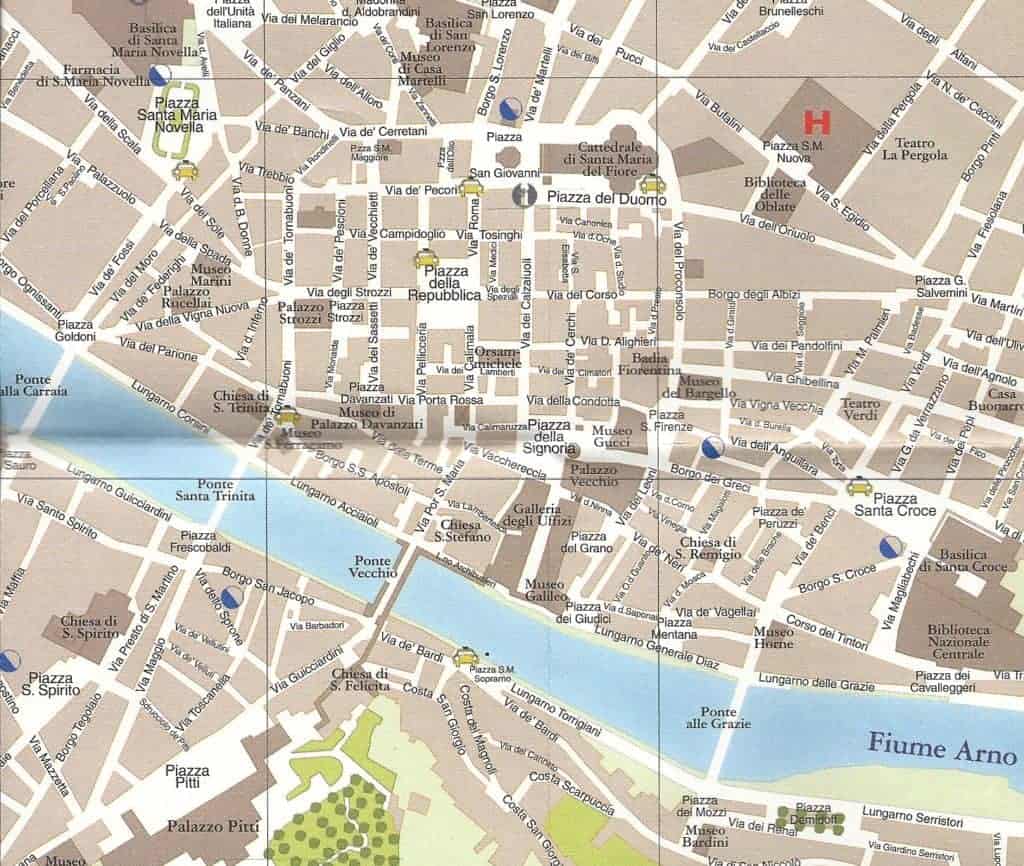

So it was with great anticipation that I took a break from operas in Vienna last month, hopped a plane across the alps, and headed for the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence. Curated with insight and largesse by Viola’s longtime collaborator and wife Kira Perov, with Arturo Galansino, the retrospective—Electronic Renaissance—honors the years Viola spent as a student and pioneer videographer in Florence. Indeed, the city opened its doors to Viola’s work, displaying pieces in multiiple sites from the Museo del Duomo to the entire Palazzo Strozzi.

So it was with great anticipation that I took a break from operas in Vienna last month, hopped a plane across the alps, and headed for the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence. Curated with insight and largesse by Viola’s longtime collaborator and wife Kira Perov, with Arturo Galansino, the retrospective—Electronic Renaissance—honors the years Viola spent as a student and pioneer videographer in Florence. Indeed, the city opened its doors to Viola’s work, displaying pieces in multiiple sites from the Museo del Duomo to the entire Palazzo Strozzi.

The real attraction for me was the chance to see Viola’s large video panels mounted in proximity with the Renaissance and Mannerist works that evoked and inspired his shimmering works. And as I had hoped, in each of the palazzo’s vaulted chambers, Renaissance works and Viola’s response faced each other, called to each other, and reinforced each other’s creative origins.

Like many of you, I had seen several of Viola’s pieces years ago at The Getty, and was familiar with his technique of hyper attenuated movement. The smallest blink of an eye, or grasp of a hand—actually happening in seconds—is stretched and lengthened into many minutes. The gestures seems to develop and bloom as we watch. Time itself unfolds through Viola’s unblinking camera, and an unseen symbolic power is revealed.

Like many of you, I had seen several of Viola’s pieces years ago at The Getty, and was familiar with his technique of hyper attenuated movement. The smallest blink of an eye, or grasp of a hand—actually happening in seconds—is stretched and lengthened into many minutes. The gestures seems to develop and bloom as we watch. Time itself unfolds through Viola’s unblinking camera, and an unseen symbolic power is revealed.

I had wandered through the cool forest of Going Forth by Day when I saw one of its five panels in Milan several years ago. Walking with the lifesized travelers of the 30 foot LED installation as they proceeded slowly across a darkened room in Florence was to enter onto a pilgrim’s journey. From room to room, I was transfixed by the glowing installations. The Crossing, one of Viola’s most famous pieces, hung suspended in the center of one huge room. On one side of the screen a man is very slowly consumed by flames as the sound system roars and crackles. On the other side, the same man is gradually, bombarded by a torrent of water, a savage deluge into which his body ultimately disappears. All that remains is the echoing of water, drop by drop. The Crossing is the most literal portrayal of Viola’s inquiry into archetypal moments of transition, of change, of ephemerality. To be human, is to be always not quite what we are. Fire and water are two moments of a single event horizon.

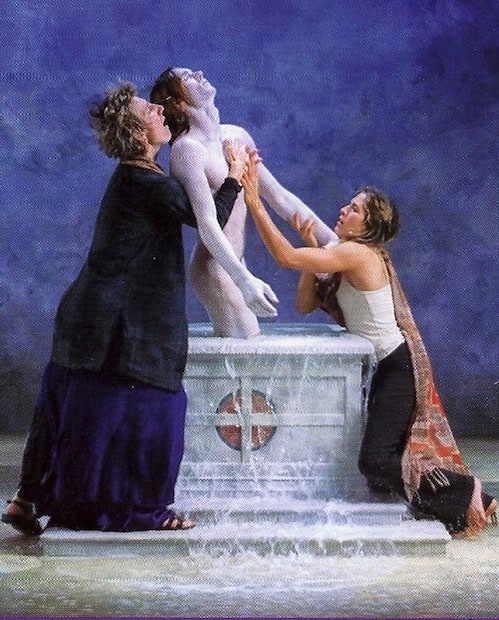

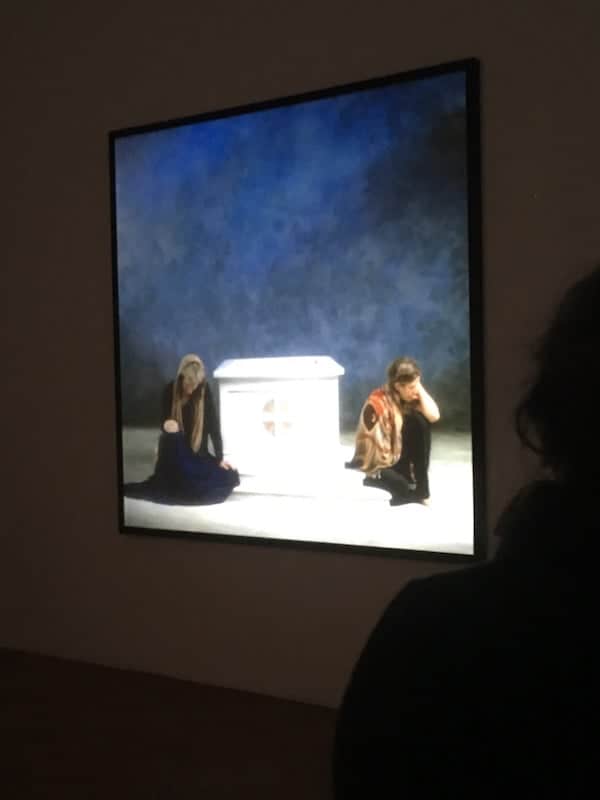

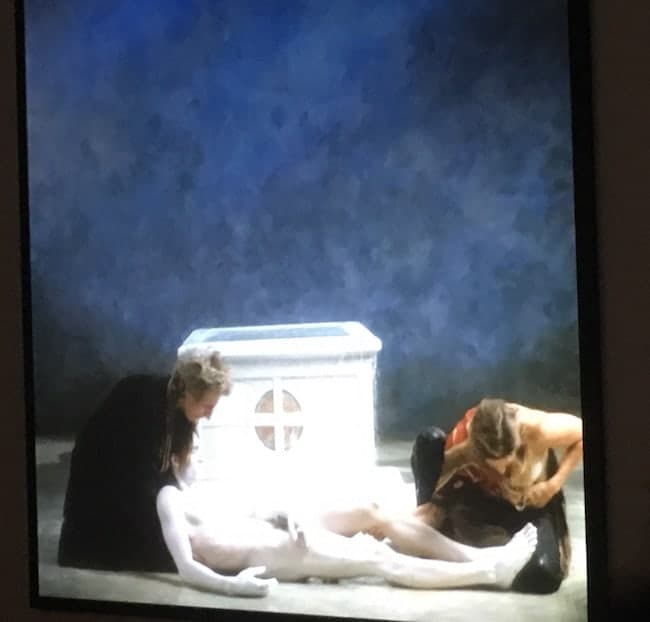

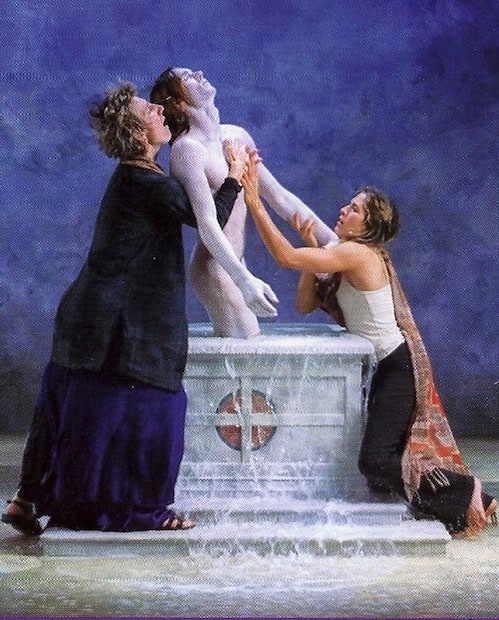

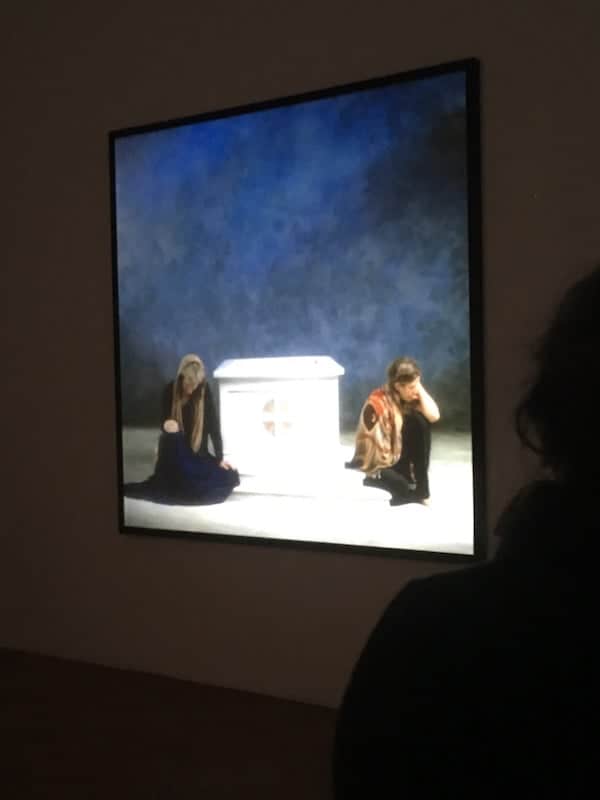

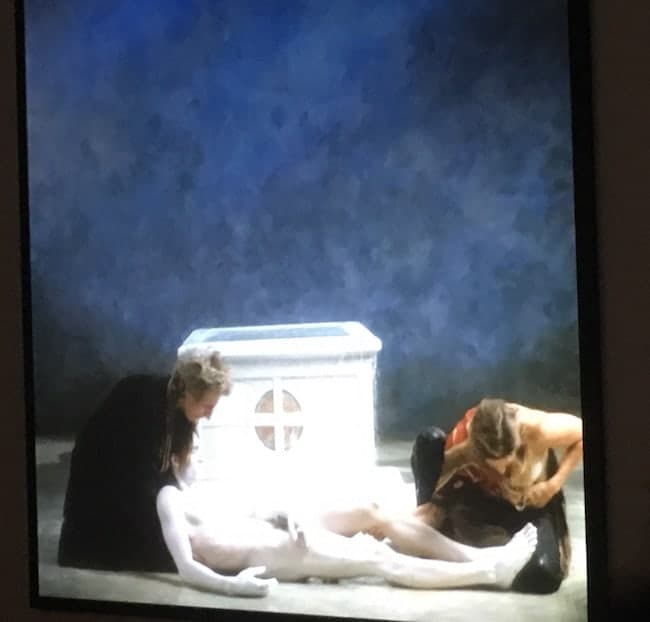

The Emergence, based upon an enigmatic and solumn 15th century work by Masolino is the exhibition’s signature work, and one in which Viola documents the naked Christ figure, emerging (as in a resurrection) and also ascending from a watery death, tenderly wrapped by two women (his mother Mary and the Magdalen, as the new testament tells it).

The Emergence, based upon an enigmatic and solumn 15th century work by Masolino is the exhibition’s signature work, and one in which Viola documents the naked Christ figure, emerging (as in a resurrection) and also ascending from a watery death, tenderly wrapped by two women (his mother Mary and the Magdalen, as the new testament tells it).

Displaying over a period of 15 minutes, the work uses its fascinating beauty (we are always wondering how it was made, noticing the arduousness of the actors’ movements) to enunciate a mysterious truth. We are watching a familiar moment, a primal moment we know in our bodies. Yet that moment has no name. It is deeper than naming. Viola knows that. The piece is nothing short of profound, kept watch over by the original Masolino alterpiece.

Displaying over a period of 15 minutes, the work uses its fascinating beauty (we are always wondering how it was made, noticing the arduousness of the actors’ movements) to enunciate a mysterious truth. We are watching a familiar moment, a primal moment we know in our bodies. Yet that moment has no name. It is deeper than naming. Viola knows that. The piece is nothing short of profound, kept watch over by the original Masolino alterpiece.

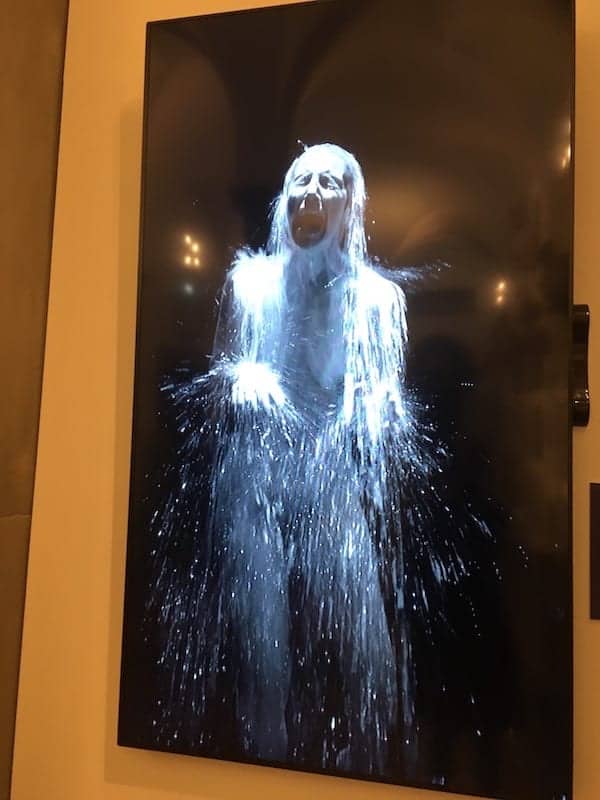

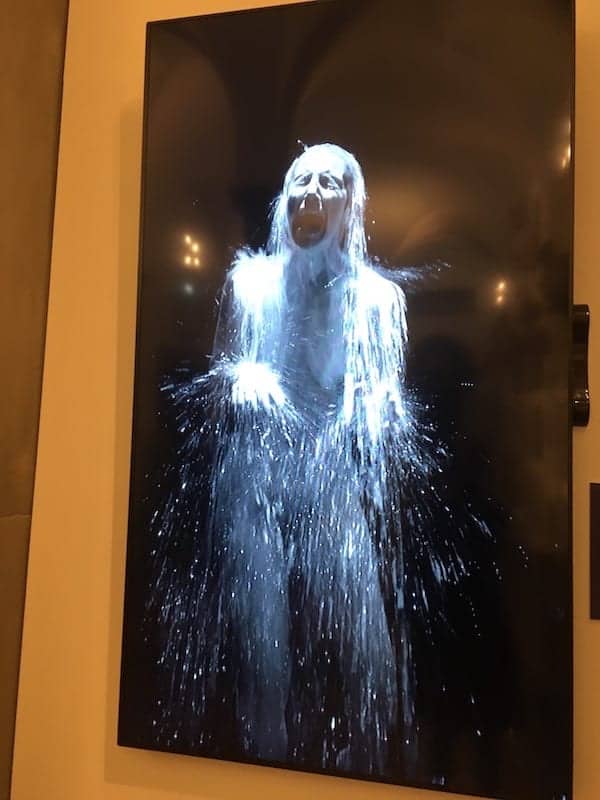

Dinner of pappardelle and wild boar ragu, chased with Chianti Classico. Next morning I saw more Viola pieces at the Museo del Opera del Duomo, and was ensnared in the tragic mirroring of Donatello‘s carved wood Magdalen—a work of numbing sorrow with Viola’s Acceptance—a lifesize video of a wailing nude woman inundated with torrents of water. The carved wooden animal hides covering the Magdalen were exactly echoed by the roiling flood, a stream of slow-motion tears. Stunned, I headed back for a second viewing of the Palazzo Strozzi show. Ten dollars was never better spent.

Dinner of pappardelle and wild boar ragu, chased with Chianti Classico. Next morning I saw more Viola pieces at the Museo del Opera del Duomo, and was ensnared in the tragic mirroring of Donatello‘s carved wood Magdalen—a work of numbing sorrow with Viola’s Acceptance—a lifesize video of a wailing nude woman inundated with torrents of water. The carved wooden animal hides covering the Magdalen were exactly echoed by the roiling flood, a stream of slow-motion tears. Stunned, I headed back for a second viewing of the Palazzo Strozzi show. Ten dollars was never better spent.

And here I walked into my own epiphany. I moved from darkened room to darkened room on Viola’s shamanic journey. The exhibition had cast a hypnotic spell, into which I, the seeker, descended deeper and deeper until I came to the room with a piece I had known about for many years—Catherine’s Room. Five panels showing the stages of a life, the time of life (youth, middle-age, etc.) symbolized by the view of a tree outside Catherin’e window. In her youth, the tree is beginning to bloom. As she grows into maturity, the tree is seen awash with green leaves, the sun high in the sky. As she grows older, the sky outside grows darker, the tree’s leaves fall. In the final panel, we watch as she makes her bed and lies down in it pulling up the covers. The window is dark, night has fallen.

And here I walked into my own epiphany. I moved from darkened room to darkened room on Viola’s shamanic journey. The exhibition had cast a hypnotic spell, into which I, the seeker, descended deeper and deeper until I came to the room with a piece I had known about for many years—Catherine’s Room. Five panels showing the stages of a life, the time of life (youth, middle-age, etc.) symbolized by the view of a tree outside Catherin’e window. In her youth, the tree is beginning to bloom. As she grows into maturity, the tree is seen awash with green leaves, the sun high in the sky. As she grows older, the sky outside grows darker, the tree’s leaves fall. In the final panel, we watch as she makes her bed and lies down in it pulling up the covers. The window is dark, night has fallen.

Each panel is also a video piece, so we can watch each image unfold in slow-motion time. And we can take it all in at once, embrace the entire polyptych as a whole.

Each panel is also a video piece, so we can watch each image unfold in slow-motion time. And we can take it all in at once, embrace the entire polyptych as a whole.

In the next to last panel, Catherine begins to light a large array of votive candles. One by one, each candle is patiently lit until the whole image is ablaze with flickering light. Going back and forth among the panels I suddenly realized that Viola was using his Buddhist savvy (agenda?) to reveal the life of a saint (a medieval panel of St. Catherine of Siena’s life faces the Viola installation). But he also showed me much more. All the moments, milestones, events of a human life occur simultaneously. Not sequentially. Everything is now. Change, movement, youth, age, birth, death—are all illusions, mere words. Catherine’s Room is every room. Her activities occur outside linear time.

I also realized the obviousness of my response. And its profundity.

There is more I can say about this exhibition. But for now, this will have to suffice. I’m still shaken by the effect of this particular suite of images—the past masters, and Bill Viola’s mastery.

Bill Viola:Electronic Renaissance. Through July 23, 2017 at the Palazzo Strozzi, Florence. If you’re anywhere near Italy in the next month, see this show!

On the Other Hand

by Christina Waters | May 31, 2017 | Art, Home, Travel |

My bags are always packed!

To go from here to there is to indulge in a blend of aesthetic schizophrenia, wanderlust, and bad faith. Insisting that I love exactly where I live, I still climb onto a plane roughly once a year to become whatever the next large foreign city can make of me. Without giving up what I have, I crave what can only be gained sitting at an exotic (df. of foreign origin) table.

The Other Place vs Home. Each has exactly what the other lacks. The foreign city has architecture, history, and the cultural depth that only a critical mass of people, talent, and creative pressure can create. [It might also offer the spectacle of Korean newlyweds posing for nuptial photos with the Uffizi in the background.]

The Other Place vs Home. Each has exactly what the other lacks. The foreign city has architecture, history, and the cultural depth that only a critical mass of people, talent, and creative pressure can create. [It might also offer the spectacle of Korean newlyweds posing for nuptial photos with the Uffizi in the background.]

The small seaside town has coziness, hominess, familiarity. Its smaller size allows for intimacy, a sense of geographical mastery that comes with manageable scale. And it is home, a place one has lived in for years. It contains friends, lovers, colleagues—all those whose ideas and eccentricities help construct your own life.

The small seaside town has coziness, hominess, familiarity. Its smaller size allows for intimacy, a sense of geographical mastery that comes with manageable scale. And it is home, a place one has lived in for years. It contains friends, lovers, colleagues—all those whose ideas and eccentricities help construct your own life.

Somewhere in the exact middle of these two attractive places the wanderer is suspended, not wanting to upset that balance, not wanting to have to choose.

I travel partly in order to see my home from a clearer vantage point, and nothing clarifies like distance (Antonioni knew that. So did Hemingway, and Durrell.) But also to feast and fill up upon the riches of the other—another time, another cultural sensibility, another way of moving, talking, and listening.

The smell of frankincense that fills the high altar of a cathedral on Sunday mornings speaks to my subconscious DNA. Was I a priest in a past life? The sound of church bells, counting out the hours, calling people to prayer, announcing this or another civic event, is part of the atmospheric soundtrack of European cities. A soundtrack missing from seaside California.

The smell of frankincense that fills the high altar of a cathedral on Sunday mornings speaks to my subconscious DNA. Was I a priest in a past life? The sound of church bells, counting out the hours, calling people to prayer, announcing this or another civic event, is part of the atmospheric soundtrack of European cities. A soundtrack missing from seaside California.

Admiring the bravura of men’s fashion in Italy I am forced to grasp the casual attire of coastal California. I see no baseball caps in Vienna, and I instantly understand the climate, the sun, the outdoor lifestyle that produces our dress code. It’s harder to see when you are in the midst, easy to spot via the extreme contrast of a metropolitan European city founded thousands of years ago by Celts.

I discovered BBC when I was in Paris several decades ago. Even though I loved French TV, the mesmerizing commercials, and pungently-dramatic soap operas, I wanted to hear some of my native language. That’s when I realized that American TV carried on as if there were no weather issues in Africa. No one mentioned incidents in the Sudan, or Myanmar. Chinese business deals weren’t given a second of air time. Bulgaria didn’t exist. The world into which I had traveled was not only larger, but my own country and its media prejudices seemed provincial by comparison.

Without question we see ourselves and our cultural assumptions more clearly from afar. Travel removes me from work. I leave my laptop at home. I am frugal with my emails. Here and now details tend to define each day. I visit a museum in Florence and find it filled with engaged high school groups. I visit a Monet show in San Francisco and find it filled with white-haired nostalgics. The youthful energy and passion for the arts in Europe is both encouraging (I envy the Europeans) and sad (I am brusquely reminded of the inattention to art of the past by student-aged Americans). Yes, opera is expensive, but the queue for cheap standing room is a block-long in Vienna. All young people. Outside the US, museum tickets are inexpensive and everyone seems to take advantage of the sensory feast and stimulus to the imagination provided by innovatively-curated exhibitions. And no, I don’t mean simply parading out the content of a wealthy woman’s closet and calling it an art exhibition.

Without question we see ourselves and our cultural assumptions more clearly from afar. Travel removes me from work. I leave my laptop at home. I am frugal with my emails. Here and now details tend to define each day. I visit a museum in Florence and find it filled with engaged high school groups. I visit a Monet show in San Francisco and find it filled with white-haired nostalgics. The youthful energy and passion for the arts in Europe is both encouraging (I envy the Europeans) and sad (I am brusquely reminded of the inattention to art of the past by student-aged Americans). Yes, opera is expensive, but the queue for cheap standing room is a block-long in Vienna. All young people. Outside the US, museum tickets are inexpensive and everyone seems to take advantage of the sensory feast and stimulus to the imagination provided by innovatively-curated exhibitions. And no, I don’t mean simply parading out the content of a wealthy woman’s closet and calling it an art exhibition.

Does travel expand our consciousness? Does the Pope suffer fools?

Bilocation and other travel puzzles

by Christina Waters | May 24, 2017 | Home, Travel |

Ah the unavoidable psycho-physical malaise of bilocation—the doubling of oneself that happens between travel and homecoming. Think of it as a variation on the mind/body problem.

Our body is spatially bound but our consciousness is adrift; e.g. somewhere near the Palazzo Vecchio, or gazing into the orchestra pit just before the overture begins. Our mind wanders in ways that our body cannot.

My hands have to be on a keyboard making sure I submit a story on time, but my imagination is unbounded by such constraints. While my body retains much of the sensory impressions of recent travel—the rolling vibration of a train ride, the feeling of the French horns thundering the entry of the gods into Valhalla—my thoughts and images are free to continue the sensory feast I’ve just seen, heard, tasted and felt.

I can still taste the sour cherry gelato I had at Corona’s at the corner of the Piazza de la Republica in Florence. I use “taste” in a quasi-metaphorical, quasi-magical sense. And because I can still taste it, I can still be there, feeling the afternoon sun, hearing the bells ringing six o’clock.

I can still taste the sour cherry gelato I had at Corona’s at the corner of the Piazza de la Republica in Florence. I use “taste” in a quasi-metaphorical, quasi-magical sense. And because I can still taste it, I can still be there, feeling the afternoon sun, hearing the bells ringing six o’clock.

The sensation of being both here and there lingers as if the body had been imprinted with the entire movement, architecture, music, flavors, and visual feasts of the duration of being far away. All of it inhabits me. I bring it back when I return and try to keep it close. I recite my memories of each day of travel, everything I saw, the people I met, the wines I tasted, and as I recite these experiences—telling them to myself, and to others—I keep the illusion of “being there” intact. But soon all those pungent and vital impressions start to fade, much as footsteps in the sand gradually eroding by the force of the tides.

Soon the feeling of being in a single space, the place of “now” solidifies. It becomes firm. I am no longer far away, no longer in the midst of travel, I am back. I am here, in a single location. And the minute I feel that, I am corraled by a single here and present. And I ache for the freedom of travel. And I want to get back on a plane and expand myself into that other location. I want to double my self, my life, my days for as long, and as many as I can.

Soon the feeling of being in a single space, the place of “now” solidifies. It becomes firm. I am no longer far away, no longer in the midst of travel, I am back. I am here, in a single location. And the minute I feel that, I am corraled by a single here and present. And I ache for the freedom of travel. And I want to get back on a plane and expand myself into that other location. I want to double my self, my life, my days for as long, and as many as I can.

It is an ever-receding horizon. An illusion. Fata morgana.

Also, there was something else new—the curtain remained up for a full 20 minutes during the first intermission so that audience could watch some of the fascinating work of moving, altering, and rearranging the key elements of the set. As stage crew—there are 57 working on this production—began altering the stage elements, two production directors explained some of the behind-the-scenes operations to the audience, most of whom stayed to watch. For some of us, this breaks the spell, but for others—who enjoy this sort of backstage revelation seen in the Metropolitan Opera HD simulcasts—it provided an invitation to learn more, and want to see more of live opera.

Also, there was something else new—the curtain remained up for a full 20 minutes during the first intermission so that audience could watch some of the fascinating work of moving, altering, and rearranging the key elements of the set. As stage crew—there are 57 working on this production—began altering the stage elements, two production directors explained some of the behind-the-scenes operations to the audience, most of whom stayed to watch. For some of us, this breaks the spell, but for others—who enjoy this sort of backstage revelation seen in the Metropolitan Opera HD simulcasts—it provided an invitation to learn more, and want to see more of live opera.

While the gorgeous Martina Serafin looked every inch an imperious princess—imagined by Puccini as an imperial icon of ice and fire—she, much as Nina Stemme in last year’s Met production—had difficulty, especially in the impossibly high and relentess second act aria— her voice struggling with a distracting vibrato as she attempted to maintain the difficult passages. While she regained her vocal beauty in the final scenes (except when she utterly missed the final highest pitches), she seemed to lack the clarity and unforced beauty of soprano Toni Marie Palmertree, who as the luckless Liu was given much the better music to sing. The irony, for me, was that I had come to this particular performance of Turandot specifically to hear Serafin, whom I’d heard as a fabulous Tosca (opposite no less than Jonas Kaufmann) in Vienna in May.

While the gorgeous Martina Serafin looked every inch an imperious princess—imagined by Puccini as an imperial icon of ice and fire—she, much as Nina Stemme in last year’s Met production—had difficulty, especially in the impossibly high and relentess second act aria— her voice struggling with a distracting vibrato as she attempted to maintain the difficult passages. While she regained her vocal beauty in the final scenes (except when she utterly missed the final highest pitches), she seemed to lack the clarity and unforced beauty of soprano Toni Marie Palmertree, who as the luckless Liu was given much the better music to sing. The irony, for me, was that I had come to this particular performance of Turandot specifically to hear Serafin, whom I’d heard as a fabulous Tosca (opposite no less than Jonas Kaufmann) in Vienna in May.

On the adjacent wall, Viola’s larger-than-lifesize figures strain against time and space in hyper slow motion, re-imagining the meeting (the piece is called The Greeting) among Mary, Elizabeth, and a third woman. Gracefully surging skirts, arms reaching out, hands about to clasp, faces registering surprise, delight, and puzzlement, Viola’s work—which takes time to unfold— forces us deep into and beneath the minds of his subjects.

On the adjacent wall, Viola’s larger-than-lifesize figures strain against time and space in hyper slow motion, re-imagining the meeting (the piece is called The Greeting) among Mary, Elizabeth, and a third woman. Gracefully surging skirts, arms reaching out, hands about to clasp, faces registering surprise, delight, and puzzlement, Viola’s work—which takes time to unfold— forces us deep into and beneath the minds of his subjects. The slowed-down movements and gestures cast digital congianti onto the image painted by Bronzino’s teacher in the early 16th century. Movement inflects stillness with layers of temporal depth. Absolutely stunning. Viola’s forensic probing of an emotion-drenched moment retrieves fresh sensations we can almost taste.

The slowed-down movements and gestures cast digital congianti onto the image painted by Bronzino’s teacher in the early 16th century. Movement inflects stillness with layers of temporal depth. Absolutely stunning. Viola’s forensic probing of an emotion-drenched moment retrieves fresh sensations we can almost taste. The Pontormo is triumphant, its colors brilliant as if freshly painted. A commanding palette of draped robes challenges the crimson dress worn Viola’s Mary, the magenta shawl of Elizabeth.The two works now share a secret, at once timeless and yet produced across and through time; they murmur of the same epic event. They are in league with each other. Sono insieme.

The Pontormo is triumphant, its colors brilliant as if freshly painted. A commanding palette of draped robes challenges the crimson dress worn Viola’s Mary, the magenta shawl of Elizabeth.The two works now share a secret, at once timeless and yet produced across and through time; they murmur of the same epic event. They are in league with each other. Sono insieme. So it was with great anticipation that I took a break from operas in Vienna last month, hopped a plane across the alps, and headed for the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence. Curated with insight and largesse by Viola’s longtime collaborator and wife Kira Perov, with Arturo Galansino, the retrospective—Electronic Renaissance—honors the years Viola spent as a student and pioneer videographer in Florence. Indeed, the city opened its doors to Viola’s work, displaying pieces in multiiple sites from the Museo del Duomo to the entire Palazzo Strozzi.

So it was with great anticipation that I took a break from operas in Vienna last month, hopped a plane across the alps, and headed for the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence. Curated with insight and largesse by Viola’s longtime collaborator and wife Kira Perov, with Arturo Galansino, the retrospective—Electronic Renaissance—honors the years Viola spent as a student and pioneer videographer in Florence. Indeed, the city opened its doors to Viola’s work, displaying pieces in multiiple sites from the Museo del Duomo to the entire Palazzo Strozzi. Like many of you, I had seen several of Viola’s pieces years ago at The Getty, and was familiar with his technique of hyper attenuated movement. The smallest blink of an eye, or grasp of a hand—actually happening in seconds—is stretched and lengthened into many minutes. The gestures seems to develop and bloom as we watch. Time itself unfolds through Viola’s unblinking camera, and an unseen symbolic power is revealed.

Like many of you, I had seen several of Viola’s pieces years ago at The Getty, and was familiar with his technique of hyper attenuated movement. The smallest blink of an eye, or grasp of a hand—actually happening in seconds—is stretched and lengthened into many minutes. The gestures seems to develop and bloom as we watch. Time itself unfolds through Viola’s unblinking camera, and an unseen symbolic power is revealed. The Emergence, based upon an enigmatic and solumn 15th century work by Masolino is the exhibition’s signature work, and one in which Viola documents the naked Christ figure, emerging (as in a resurrection) and also ascending from a watery death, tenderly wrapped by two women (his mother Mary and the Magdalen, as the new testament tells it).

The Emergence, based upon an enigmatic and solumn 15th century work by Masolino is the exhibition’s signature work, and one in which Viola documents the naked Christ figure, emerging (as in a resurrection) and also ascending from a watery death, tenderly wrapped by two women (his mother Mary and the Magdalen, as the new testament tells it). Displaying over a period of 15 minutes, the work uses its fascinating beauty (we are always wondering how it was made, noticing the arduousness of the actors’ movements) to enunciate a mysterious truth. We are watching a familiar moment, a primal moment we know in our bodies. Yet that moment has no name. It is deeper than naming. Viola knows that. The piece is nothing short of profound, kept watch over by the original Masolino alterpiece.

Displaying over a period of 15 minutes, the work uses its fascinating beauty (we are always wondering how it was made, noticing the arduousness of the actors’ movements) to enunciate a mysterious truth. We are watching a familiar moment, a primal moment we know in our bodies. Yet that moment has no name. It is deeper than naming. Viola knows that. The piece is nothing short of profound, kept watch over by the original Masolino alterpiece. Dinner of pappardelle and wild boar ragu, chased with Chianti Classico. Next morning I saw more Viola pieces at the Museo del Opera del Duomo, and was ensnared in the tragic mirroring of Donatello‘s carved wood Magdalen—a work of numbing sorrow with Viola’s Acceptance—a lifesize video of a wailing nude woman inundated with torrents of water. The carved wooden animal hides covering the Magdalen were exactly echoed by the roiling flood, a stream of slow-motion tears. Stunned, I headed back for a second viewing of the Palazzo Strozzi show. Ten dollars was never better spent.

Dinner of pappardelle and wild boar ragu, chased with Chianti Classico. Next morning I saw more Viola pieces at the Museo del Opera del Duomo, and was ensnared in the tragic mirroring of Donatello‘s carved wood Magdalen—a work of numbing sorrow with Viola’s Acceptance—a lifesize video of a wailing nude woman inundated with torrents of water. The carved wooden animal hides covering the Magdalen were exactly echoed by the roiling flood, a stream of slow-motion tears. Stunned, I headed back for a second viewing of the Palazzo Strozzi show. Ten dollars was never better spent. And here I walked into my own epiphany. I moved from darkened room to darkened room on Viola’s shamanic journey. The exhibition had cast a hypnotic spell, into which I, the seeker, descended deeper and deeper until I came to the room with a piece I had known about for many years—Catherine’s Room. Five panels showing the stages of a life, the time of life (youth, middle-age, etc.) symbolized by the view of a tree outside Catherin’e window. In her youth, the tree is beginning to bloom. As she grows into maturity, the tree is seen awash with green leaves, the sun high in the sky. As she grows older, the sky outside grows darker, the tree’s leaves fall. In the final panel, we watch as she makes her bed and lies down in it pulling up the covers. The window is dark, night has fallen.

And here I walked into my own epiphany. I moved from darkened room to darkened room on Viola’s shamanic journey. The exhibition had cast a hypnotic spell, into which I, the seeker, descended deeper and deeper until I came to the room with a piece I had known about for many years—Catherine’s Room. Five panels showing the stages of a life, the time of life (youth, middle-age, etc.) symbolized by the view of a tree outside Catherin’e window. In her youth, the tree is beginning to bloom. As she grows into maturity, the tree is seen awash with green leaves, the sun high in the sky. As she grows older, the sky outside grows darker, the tree’s leaves fall. In the final panel, we watch as she makes her bed and lies down in it pulling up the covers. The window is dark, night has fallen. Each panel is also a video piece, so we can watch each image unfold in slow-motion time. And we can take it all in at once, embrace the entire polyptych as a whole.

Each panel is also a video piece, so we can watch each image unfold in slow-motion time. And we can take it all in at once, embrace the entire polyptych as a whole.

The Other Place vs Home. Each has exactly what the other lacks. The foreign city has architecture, history, and the cultural depth that only a critical mass of people, talent, and creative pressure can create. [It might also offer the spectacle of Korean newlyweds posing for nuptial photos with the Uffizi in the background.]

The Other Place vs Home. Each has exactly what the other lacks. The foreign city has architecture, history, and the cultural depth that only a critical mass of people, talent, and creative pressure can create. [It might also offer the spectacle of Korean newlyweds posing for nuptial photos with the Uffizi in the background.]    The small seaside town has coziness, hominess, familiarity. Its smaller size allows for intimacy, a sense of geographical mastery that comes with manageable scale. And it is home, a place one has lived in for years. It contains friends, lovers, colleagues—all those whose ideas and eccentricities help construct your own life.

The small seaside town has coziness, hominess, familiarity. Its smaller size allows for intimacy, a sense of geographical mastery that comes with manageable scale. And it is home, a place one has lived in for years. It contains friends, lovers, colleagues—all those whose ideas and eccentricities help construct your own life. The smell of frankincense that fills the high altar of a cathedral on Sunday mornings speaks to my subconscious DNA. Was I a priest in a past life? The sound of church bells, counting out the hours, calling people to prayer, announcing this or another civic event, is part of the atmospheric soundtrack of European cities. A soundtrack missing from seaside California.

The smell of frankincense that fills the high altar of a cathedral on Sunday mornings speaks to my subconscious DNA. Was I a priest in a past life? The sound of church bells, counting out the hours, calling people to prayer, announcing this or another civic event, is part of the atmospheric soundtrack of European cities. A soundtrack missing from seaside California. Without question we see ourselves and our cultural assumptions more clearly from afar. Travel removes me from work. I leave my laptop at home. I am frugal with my emails. Here and now details tend to define each day. I visit a museum in Florence and find it filled with engaged high school groups. I visit a Monet show in San Francisco and find it filled with white-haired nostalgics. The youthful energy and passion for the arts in Europe is both encouraging (I envy the Europeans) and sad (I am brusquely reminded of the inattention to art of the past by student-aged Americans). Yes, opera is expensive, but the queue for cheap standing room is a block-long in Vienna. All young people. Outside the US, museum tickets are inexpensive and everyone seems to take advantage of the sensory feast and stimulus to the imagination provided by innovatively-curated exhibitions. And no, I don’t mean simply parading out the content of a wealthy woman’s closet and calling it an art exhibition.

Without question we see ourselves and our cultural assumptions more clearly from afar. Travel removes me from work. I leave my laptop at home. I am frugal with my emails. Here and now details tend to define each day. I visit a museum in Florence and find it filled with engaged high school groups. I visit a Monet show in San Francisco and find it filled with white-haired nostalgics. The youthful energy and passion for the arts in Europe is both encouraging (I envy the Europeans) and sad (I am brusquely reminded of the inattention to art of the past by student-aged Americans). Yes, opera is expensive, but the queue for cheap standing room is a block-long in Vienna. All young people. Outside the US, museum tickets are inexpensive and everyone seems to take advantage of the sensory feast and stimulus to the imagination provided by innovatively-curated exhibitions. And no, I don’t mean simply parading out the content of a wealthy woman’s closet and calling it an art exhibition.

I can still taste the sour cherry gelato I had at Corona’s at the corner of the Piazza de la Republica in Florence. I use “taste” in a quasi-metaphorical, quasi-magical sense. And because I can still taste it, I can still be there, feeling the afternoon sun, hearing the bells ringing six o’clock.

I can still taste the sour cherry gelato I had at Corona’s at the corner of the Piazza de la Republica in Florence. I use “taste” in a quasi-metaphorical, quasi-magical sense. And because I can still taste it, I can still be there, feeling the afternoon sun, hearing the bells ringing six o’clock. Soon the feeling of being in a single space, the place of “now” solidifies. It becomes firm. I am no longer far away, no longer in the midst of travel, I am back. I am here, in a single location. And the minute I feel that, I am corraled by a single here and present. And I ache for the freedom of travel. And I want to get back on a plane and expand myself into that other location. I want to double my self, my life, my days for as long, and as many as I can.

Soon the feeling of being in a single space, the place of “now” solidifies. It becomes firm. I am no longer far away, no longer in the midst of travel, I am back. I am here, in a single location. And the minute I feel that, I am corraled by a single here and present. And I ache for the freedom of travel. And I want to get back on a plane and expand myself into that other location. I want to double my self, my life, my days for as long, and as many as I can.