Here was a long-awaited experience—the chance to finally see the great Pontormo Visitation along with Bill Viola‘s haunting video response made five hundred years later. There in a single darkened room was the newly-restored Mannerist painting portraying the moment when Mary reveals to her cousin Elizabeth that she is pregnant. All the mystery and innuedo, the pungent psychological drama of what might have transpired is captured in their complex gaze, the swirling folds of the gowns, the torque of the bodies as they touch and yet turn away. Pontormo’s use of a single model for two of the figures adds a sparkle of surrealism to the moment. Mary’s mother Anne watches on, and an angel—also a witness—looks directly at us, viewers across the centuries.

On the adjacent wall, Viola’s larger-than-lifesize figures strain against time and space in hyper slow motion, re-imagining the meeting (the piece is called The Greeting) among Mary, Elizabeth, and a third woman. Gracefully surging skirts, arms reaching out, hands about to clasp, faces registering surprise, delight, and puzzlement, Viola’s work—which takes time to unfold— forces us deep into and beneath the minds of his subjects.

On the adjacent wall, Viola’s larger-than-lifesize figures strain against time and space in hyper slow motion, re-imagining the meeting (the piece is called The Greeting) among Mary, Elizabeth, and a third woman. Gracefully surging skirts, arms reaching out, hands about to clasp, faces registering surprise, delight, and puzzlement, Viola’s work—which takes time to unfold— forces us deep into and beneath the minds of his subjects.

The slowed-down movements and gestures cast digital congianti onto the image painted by Bronzino’s teacher in the early 16th century. Movement inflects stillness with layers of temporal depth. Absolutely stunning. Viola’s forensic probing of an emotion-drenched moment retrieves fresh sensations we can almost taste.

The slowed-down movements and gestures cast digital congianti onto the image painted by Bronzino’s teacher in the early 16th century. Movement inflects stillness with layers of temporal depth. Absolutely stunning. Viola’s forensic probing of an emotion-drenched moment retrieves fresh sensations we can almost taste.

The Pontormo is triumphant, its colors brilliant as if freshly painted. A commanding palette of draped robes challenges the crimson dress worn Viola’s Mary, the magenta shawl of Elizabeth.The two works now share a secret, at once timeless and yet produced across and through time; they murmur of the same epic event. They are in league with each other. Sono insieme.

The Pontormo is triumphant, its colors brilliant as if freshly painted. A commanding palette of draped robes challenges the crimson dress worn Viola’s Mary, the magenta shawl of Elizabeth.The two works now share a secret, at once timeless and yet produced across and through time; they murmur of the same epic event. They are in league with each other. Sono insieme.

I’ve taught some of the ideas and work of video artist Bill Viola in many of my courses over the past 15 years. And the more I reflect on his comments about his work, how it came into fruition, and the various influences upon them, the more my bond with his output deepens.

So it was with great anticipation that I took a break from operas in Vienna last month, hopped a plane across the alps, and headed for the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence. Curated with insight and largesse by Viola’s longtime collaborator and wife Kira Perov, with Arturo Galansino, the retrospective—Electronic Renaissance—honors the years Viola spent as a student and pioneer videographer in Florence. Indeed, the city opened its doors to Viola’s work, displaying pieces in multiiple sites from the Museo del Duomo to the entire Palazzo Strozzi.

So it was with great anticipation that I took a break from operas in Vienna last month, hopped a plane across the alps, and headed for the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence. Curated with insight and largesse by Viola’s longtime collaborator and wife Kira Perov, with Arturo Galansino, the retrospective—Electronic Renaissance—honors the years Viola spent as a student and pioneer videographer in Florence. Indeed, the city opened its doors to Viola’s work, displaying pieces in multiiple sites from the Museo del Duomo to the entire Palazzo Strozzi.

The real attraction for me was the chance to see Viola’s large video panels mounted in proximity with the Renaissance and Mannerist works that evoked and inspired his shimmering works. And as I had hoped, in each of the palazzo’s vaulted chambers, Renaissance works and Viola’s response faced each other, called to each other, and reinforced each other’s creative origins.

Like many of you, I had seen several of Viola’s pieces years ago at The Getty, and was familiar with his technique of hyper attenuated movement. The smallest blink of an eye, or grasp of a hand—actually happening in seconds—is stretched and lengthened into many minutes. The gestures seems to develop and bloom as we watch. Time itself unfolds through Viola’s unblinking camera, and an unseen symbolic power is revealed.

Like many of you, I had seen several of Viola’s pieces years ago at The Getty, and was familiar with his technique of hyper attenuated movement. The smallest blink of an eye, or grasp of a hand—actually happening in seconds—is stretched and lengthened into many minutes. The gestures seems to develop and bloom as we watch. Time itself unfolds through Viola’s unblinking camera, and an unseen symbolic power is revealed.

I had wandered through the cool forest of Going Forth by Day when I saw one of its five panels in Milan several years ago. Walking with the lifesized travelers of the 30 foot LED installation as they proceeded slowly across a darkened room in Florence was to enter onto a pilgrim’s journey. From room to room, I was transfixed by the glowing installations. The Crossing, one of Viola’s most famous pieces, hung suspended in the center of one huge room. On one side of the screen a man is very slowly consumed by flames as the sound system roars and crackles. On the other side, the same man is gradually, bombarded by a torrent of water, a savage deluge into which his body ultimately disappears. All that remains is the echoing of water, drop by drop. The Crossing is the most literal portrayal of Viola’s inquiry into archetypal moments of transition, of change, of ephemerality. To be human, is to be always not quite what we are. Fire and water are two moments of a single event horizon.

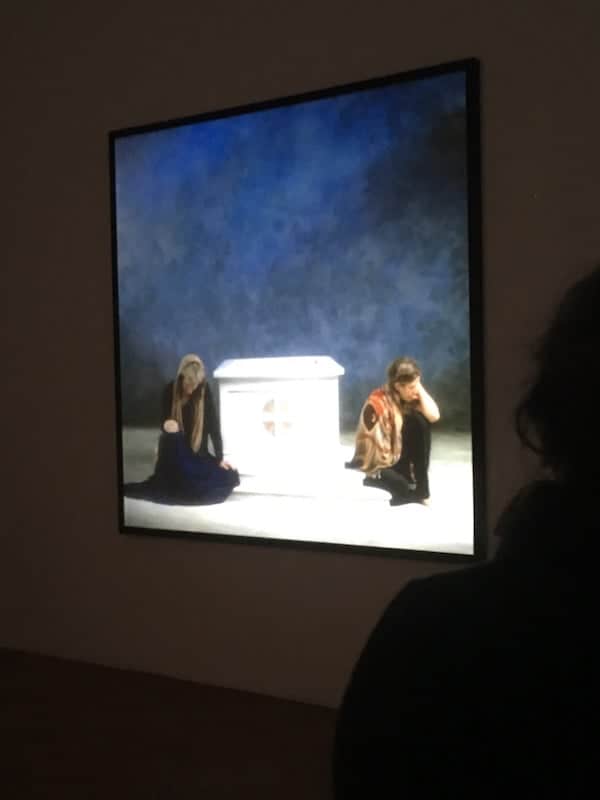

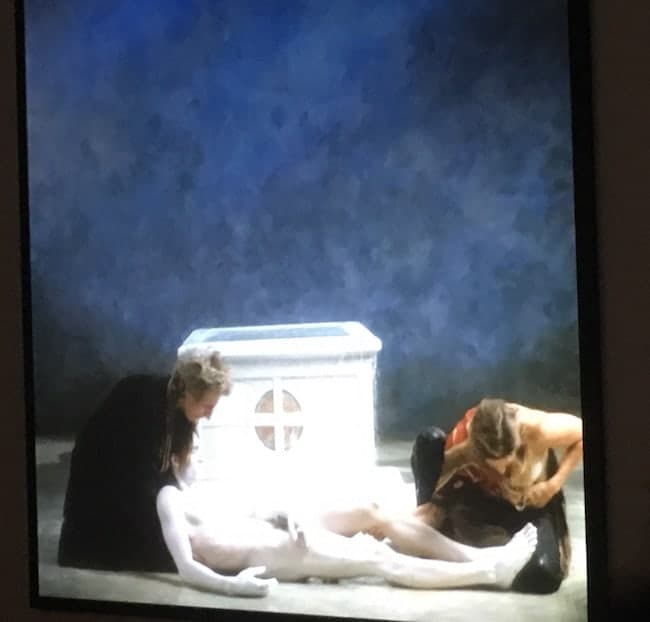

The Emergence, based upon an enigmatic and solumn 15th century work by Masolino is the exhibition’s signature work, and one in which Viola documents the naked Christ figure, emerging (as in a resurrection) and also ascending from a watery death, tenderly wrapped by two women (his mother Mary and the Magdalen, as the new testament tells it).

The Emergence, based upon an enigmatic and solumn 15th century work by Masolino is the exhibition’s signature work, and one in which Viola documents the naked Christ figure, emerging (as in a resurrection) and also ascending from a watery death, tenderly wrapped by two women (his mother Mary and the Magdalen, as the new testament tells it).

Displaying over a period of 15 minutes, the work uses its fascinating beauty (we are always wondering how it was made, noticing the arduousness of the actors’ movements) to enunciate a mysterious truth. We are watching a familiar moment, a primal moment we know in our bodies. Yet that moment has no name. It is deeper than naming. Viola knows that. The piece is nothing short of profound, kept watch over by the original Masolino alterpiece.

Displaying over a period of 15 minutes, the work uses its fascinating beauty (we are always wondering how it was made, noticing the arduousness of the actors’ movements) to enunciate a mysterious truth. We are watching a familiar moment, a primal moment we know in our bodies. Yet that moment has no name. It is deeper than naming. Viola knows that. The piece is nothing short of profound, kept watch over by the original Masolino alterpiece.

Dinner of pappardelle and wild boar ragu, chased with Chianti Classico. Next morning I saw more Viola pieces at the Museo del Opera del Duomo, and was ensnared in the tragic mirroring of Donatello‘s carved wood Magdalen—a work of numbing sorrow with Viola’s Acceptance—a lifesize video of a wailing nude woman inundated with torrents of water. The carved wooden animal hides covering the Magdalen were exactly echoed by the roiling flood, a stream of slow-motion tears. Stunned, I headed back for a second viewing of the Palazzo Strozzi show. Ten dollars was never better spent.

Dinner of pappardelle and wild boar ragu, chased with Chianti Classico. Next morning I saw more Viola pieces at the Museo del Opera del Duomo, and was ensnared in the tragic mirroring of Donatello‘s carved wood Magdalen—a work of numbing sorrow with Viola’s Acceptance—a lifesize video of a wailing nude woman inundated with torrents of water. The carved wooden animal hides covering the Magdalen were exactly echoed by the roiling flood, a stream of slow-motion tears. Stunned, I headed back for a second viewing of the Palazzo Strozzi show. Ten dollars was never better spent.

And here I walked into my own epiphany. I moved from darkened room to darkened room on Viola’s shamanic journey. The exhibition had cast a hypnotic spell, into which I, the seeker, descended deeper and deeper until I came to the room with a piece I had known about for many years—Catherine’s Room. Five panels showing the stages of a life, the time of life (youth, middle-age, etc.) symbolized by the view of a tree outside Catherin’e window. In her youth, the tree is beginning to bloom. As she grows into maturity, the tree is seen awash with green leaves, the sun high in the sky. As she grows older, the sky outside grows darker, the tree’s leaves fall. In the final panel, we watch as she makes her bed and lies down in it pulling up the covers. The window is dark, night has fallen.

And here I walked into my own epiphany. I moved from darkened room to darkened room on Viola’s shamanic journey. The exhibition had cast a hypnotic spell, into which I, the seeker, descended deeper and deeper until I came to the room with a piece I had known about for many years—Catherine’s Room. Five panels showing the stages of a life, the time of life (youth, middle-age, etc.) symbolized by the view of a tree outside Catherin’e window. In her youth, the tree is beginning to bloom. As she grows into maturity, the tree is seen awash with green leaves, the sun high in the sky. As she grows older, the sky outside grows darker, the tree’s leaves fall. In the final panel, we watch as she makes her bed and lies down in it pulling up the covers. The window is dark, night has fallen.

Each panel is also a video piece, so we can watch each image unfold in slow-motion time. And we can take it all in at once, embrace the entire polyptych as a whole.

Each panel is also a video piece, so we can watch each image unfold in slow-motion time. And we can take it all in at once, embrace the entire polyptych as a whole.

In the next to last panel, Catherine begins to light a large array of votive candles. One by one, each candle is patiently lit until the whole image is ablaze with flickering light. Going back and forth among the panels I suddenly realized that Viola was using his Buddhist savvy (agenda?) to reveal the life of a saint (a medieval panel of St. Catherine of Siena’s life faces the Viola installation). But he also showed me much more. All the moments, milestones, events of a human life occur simultaneously. Not sequentially. Everything is now. Change, movement, youth, age, birth, death—are all illusions, mere words. Catherine’s Room is every room. Her activities occur outside linear time.

I also realized the obviousness of my response. And its profundity.

There is more I can say about this exhibition. But for now, this will have to suffice. I’m still shaken by the effect of this particular suite of images—the past masters, and Bill Viola’s mastery.

Bill Viola:Electronic Renaissance. Through July 23, 2017 at the Palazzo Strozzi, Florence. If you’re anywhere near Italy in the next month, see this show!