by Christina Waters | Jul 6, 2022 | Home |

Parsifal: Twilight of a Production

Having traveled 5000 miles to dive into the Opera Bastille production of Wagner’s final opera, I was poised for a memorable experience. And while I certainly got one, it was mostly for the wrong reasons.

Here’s the short version.

Conducted by Wagner veteran, Simone Young, the Paris Opera gave a fine reading of music so romantically breathtaking that it defines “sublime.” Excellent throughout, the orchestra managed to hold out against a mesmerizing yet ultimately destructive production, perpetrated by director Richard Jones. The elaborate set, moving on invisible tracks to reveal ever more chambers and levels, was clever, ludicrous, puzzling, and silly.

The costumes were blatantly ugly, and while we don’t always expect singers who are svelte, or who are also good actors, we could hope for more than the baggy shorts, backpacks, and sweatshirts most of the principals had to endure. Also terrible—save for the stalwart Kwangchul Youn as Gurnemanz, and Falk Struckmann as Klingsor—the singers had their eyes glued on the conductor for most of the performance.

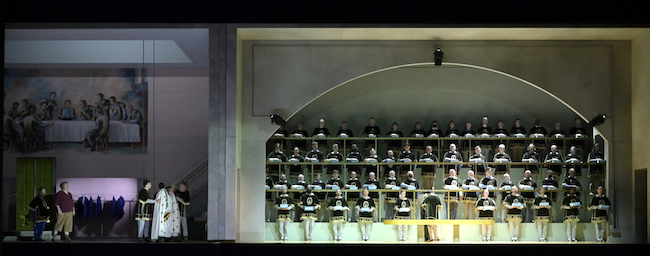

photo: Vincent PONTET

The chorus was wonderful. And even though the music simply cannot be ruined, the production design tried its hardest to cut deeply into Wagner’s spiritual vision. Trashing the concept of Parsifal’s innocence overcoming magician Klingsor’s malevolent genetic engineering, the Act 2 Set of lusty flowermaidens jiggling fake boobs and buns non-stop, was tiresome. This four-year-old production felt distinctly dated.

Nothing this production threw at the audience did anything to illuminate new vistas, or unprobed corners of this complex work of art. The final act was inexcusably boring. Three people, standing around on a nearly bare stage, singing at each other (and none too well) for over an hour.

Now for the longer version.

Conductor Simone Young moved the Paris Opera orchestra smoothly through the depths of Wagner’s final opera, the entire ensemble firmly in her eloquent hands.

The underlying spirituality of the composer’s great music-drama “consecration” came through clearly, despite the visual antagonism of an agnostic setting and shallow visual interpretation.The point is made clearly by the great horn motifs and ascending chromatics of chord structure, the rising colors of the sound as if sunlight suddenly thrusts through the rose window of a great cathedral. Music and setting contradicting each other whenever possible.

As the opera moves us through an often incomprehensible maze of myths, metaphors, and magic, the composer summarizes his own repertoire, unafraid to quote his own work, to borrow from his own splendid musical themes.

While contemporary, even futuristic visual settings are often effective in reinforcing the romantic timelessness of the story, in the case of Richard Jones’ concept quite the opposite is true. The clever but overwrought transplantation of the story into future of cultish monasticism fail to move our understanding any further. The flower maidens as GMO-creations of exhaustingly explicit sexuality—less would have been more. The elision of sports cults and religious fanaticism, while perhaps persuasive, again didn’t illuminate the overall genius of this last work of the great master.

For that, we had the music itself.

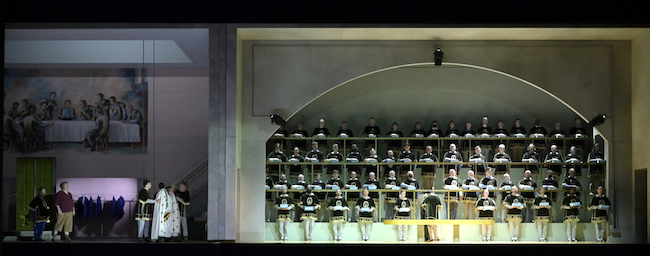

Here’s the best place to focus on the complex set, which moved laterally to reveal ever more chambers, and in some scenes multiple levels. An arresting illustration of the opera’s mythic words: “here Time becomes Space.” From the study hall of what appears to be a cult devoted to “the Word,” the set moved the actors into austere chambers containing the bleeding Gail lord Amfortas and in a small bedroom upstairs, the dying founder of the Grail knights, Tintural. As the set continued to expand, it revealed a conference room crowned by a mural of a proto-Last Supper, and finally into a huge sports arena lined with row after row of cult followers (the mighty Paris Opera choir, flawlessly trained by choral director Ching-Lien Wu).

Calling lots of attention to itself, the set was alternately effective and silly, inspired and stupid. This production by Richard Jones feels smug about itself, the clever set as visual tour de force, with robotic cult members whose movements have been honed to within a goose step. And yet without the rapture implied by the chromatically mutating music, the entire production comes off as ironic and sterile.

The complete opposite of the semi-staged Ring I went on to see in Budapest, where minimal staging allowed the music and voices to cast their spells with emotional intimacy, the Paris Parsifal felt robotic, overwhelmed, and tired. Hopefully it will be retired for something fresh. Perhaps something that has more to do with the music, and less with the sort of fashionable revisioning that can completely undercut the musical ideas. The Frank Castorf Ring in 2013 comes to mind. Or the Sebastian Baumgarten Tannhäuser in which grotesque romping monsters obliterated some of the most gorgeous music ever composed.

Photo : Vincent PONTET

In warmup suits as if about to attend a sports contest—the Paris Open perhaps?—the old faithful knight of the Grail, Gurnemanz, was given stalwart voice by Parsifal veteran Kwangchul Youn. I’d heard him in the 2014 Bayreuth production in the same role, and his resounding and tireless musicality seemed not to have aged. As the wounded Grail lord Amfortas, Iain Paterson looked and sounded exhausted. As the pure fool, Parsifal, Simon O’Neill relied on almost non-stop eye contact with conductor Young as if uncertain what his next lines should be. The mercurial time-traveling witch Kundry, dressed in hipster backpack and sweatshirt sung by Russian mezzo-soprano Marina Prudenskaya, was neither believable nor vocally engaging. By the end of the opera, she had devolved from temptress to penitent, and then finally as best buddy to the hero with whom she sauntered off-stage hand-in-hand. In Wagner’s original version, Parsifal absolves her wickedness and she gratefully swoons and dies.

The last act, incomprehensibly sung against a bare stage, is inexcusably boring. Why have the newly repentant witch Kundry, and the newly awakened Parsifal, explain their realizations in a completely empty space? Vocal precision and color might have helped. But these were alas also missing.

Would that this bewildering yet majestic music had been sung by brilliant voices. As it was, the June 6 performance left me longing to have heard the 2018 debut version of this production, with the acting genius Peter Mattei as Amfortas, heldentenor Andreas Shager as Parsifal, and the rich and adroit mezzo of Anja Kampe as Kundry. The veteran Wagnerian Falk Struckmann, as the malevolent magician Klingsor, announced through a spokesman at the start of the opera that he was not in his best form that night. My heart almost stopped. I’d been a fan since I saw him as Hagen in the Vienna Ring five years ago. A savvy actor, Struckmann performed nonetheless and even in less than perfect form he sounded better than most of the others on that stage.

The costume designer owes an apology to singers and audience Baggy clothing on Parsifal, fussy and dowdy costumes on Kundry, woefully malfunctioning fake blood on the robes of Amfortas, and the hilarious X-rated gyrations of the genetically engineered maize maidens made this Parsifal a pleasure only if you closed your eyes.

The ascending fifths of the Dresden Amen still worked their redemptive magic, and while this production makes almost nothing of the spiritual thrust of this opera, the splendid orchestra rose to the occasion. It made sense of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s confession that while he loathed the Christian theme underlying Parsifal, he had to admit the music was sublime. Sublime and worth the five hours and 5000 miles I’d traveled to enjoy.

Orchestre de l’Opéra national de Paris

by Christina Waters | Jul 6, 2022 | Home |

I’d waited for almost three years to get on a plane headed for Europe. And Paris did not disappoint. Balmy summer weather, baguettes as good as my memories, and a few days to kill roaming the city, and some great museums before my night at the opera—Parsifal—arrived.

The light rain falling as we drove into the city from Charles de Gaulle announced that I wasn’t in California anymore. Warm temperatures, day and night, noticeble humidity plus the long days of summer—sunset not until 10pm—felt especially welcoming. From my embarrassingly posh hotel across the street from the Louvre, I was able to explore a few bistros, shops, and of course the reassuring sight of Notre Dame, still splendid even surrounded by cranes and fencing.

One dinner at Paul Bocuse’s Hotel Louvre Restaurant, provided me with an impeccable Scottish salmon on a bed of potatoes, giant capers, and hazelnuts. Paired with the sort of bread that dreams are made of, and a glass of crisp Chablis, it answered a craving that had built up for several years of quarantine.

Next morning, reserved ticket in hand (or rather on my phone) I was ushered into a very short line (three people!) into the vastness of the Louvre. Avoiding the crowded line encircling the Mona Lisa, I instead re-visited a few of my favorite paintings, including a Mantegna that might have been painted yesterday, the miraculous Virgin of the Rocks, and rediscovered the genius of Jean-Louis David.

Next morning, reserved ticket in hand (or rather on my phone) I was ushered into a very short line (three people!) into the vastness of the Louvre. Avoiding the crowded line encircling the Mona Lisa, I instead re-visited a few of my favorite paintings, including a Mantegna that might have been painted yesterday, the miraculous Virgin of the Rocks, and rediscovered the genius of Jean-Louis David.

I devoured as much as I could before visual saturation set in and it was time to head up the street to Bistrot Victoires for a delicious duck confit with perfect potatoes and a glass of Côtes du Rhône.

I devoured as much as I could before visual saturation set in and it was time to head up the street to Bistrot Victoires for a delicious duck confit with perfect potatoes and a glass of Côtes du Rhône.

Followed by an espresso, the lunch confirmed my belief in Paris as a city of high culinary standards.

Followed by an espresso, the lunch confirmed my belief in Paris as a city of high culinary standards.

Next day, I sprinted across the Pont du Carousel to the Musée d’Orsay and a mini-orgy of 19th and 20th century artwork, distinguished by new and old Manets, a few choice van Goghs, and an array of gleaming Art Nouveau furniture, rugs, and candelabra.

Again, I tried to make sure I left before eye-stupor set in. I strolled up to the St. Germain neighborhood, and had an espresso at Les Deux Magots in honor of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir who often spent time smoking, drinking, and writing at this very cafe.

That evening, I walked across the river again to the exquisite Gothic jewelbox that is Saint Chapelle, built by St. Louis to house his splinter of the True Cross, and enjoyed the rare experience of an intimate concert of piano music by the heroic performer Vanessa Wagner, a woman with Bronzino arms and complete command of her instrument.

That evening, I walked across the river again to the exquisite Gothic jewelbox that is Saint Chapelle, built by St. Louis to house his splinter of the True Cross, and enjoyed the rare experience of an intimate concert of piano music by the heroic performer Vanessa Wagner, a woman with Bronzino arms and complete command of her instrument.

Only two hundred seats in the tiny upper sanctuary, still light enough at 8pm for sun to illuminate the incredible stained glass, as we listened to Mozart, Rachmaninoff, and Debussy. Acoustics as impeccable as the interior itself.

Only two hundred seats in the tiny upper sanctuary, still light enough at 8pm for sun to illuminate the incredible stained glass, as we listened to Mozart, Rachmaninoff, and Debussy. Acoustics as impeccable as the interior itself.

I sat outside on the patio of my hotel Palais Royal, with a Campari spritz, and enjoyed the feel of the soft heavy air on my face and arms. Parisians are a hundred times more diverse than we are in California, and the procession of colors and costumes, fashions and follies was almost as delicious as the cuisine.

The next evening was my night at the opera, so I enjoyed a Croque Monsieur and pommes frites at the nearby Cafe Blanc before heading out to the Opera Bastille, where I would consume only a glass of champagne and a ham and cheese sandwich during the next five hours and 15 minutes. [see my account of the opera itself in an adjoining post]

My last day in Paris I wandered through the renovated Art Nouveau interior of the enormous upscale Samaritaine department store. Then it was back to my neighborhood to the 2-star Michelin restaurant Palais Royal, where I had a long-awaited lunch reservation. Three courses, prix fixe, plus a glass of the kind of Bordeaux that makes you want to rob a bank.

Palais Royal and the handiwork of chef Philip Chronopoulos.

Armed with a pedigree that has taken him to London, Paris, and soon Venice, this chef sets an inventive tone. The room was simple, perfect, not fussy. The very young staff spoke English well, and unlike Parisian dining of yore, they smiled and made each diner feel comfortable—from the table filled with expense account businessmen to me, a solo diner splurging on what would be a memorable succession of gorgeous dishes.

The initial amuses dishes included a single deep-fried pastry pillow filled with a warm quail egg yolk. A little pastry boat filled with fresh pea puree, topped with a tangle of mâche and parmesan. A pretty salad of warm grapes and tiny beets arrived topped with a scoop of creamy feta in a pool of sweet and salty broth. And an incredible cheese straw (much more elegant than that) but essentially a finger of crisp cheese filled with veloté of foie gras—it was one of the best things I’ve ever tasted.[see below]

The initial amuses dishes included a single deep-fried pastry pillow filled with a warm quail egg yolk. A little pastry boat filled with fresh pea puree, topped with a tangle of mâche and parmesan. A pretty salad of warm grapes and tiny beets arrived topped with a scoop of creamy feta in a pool of sweet and salty broth. And an incredible cheese straw (much more elegant than that) but essentially a finger of crisp cheese filled with veloté of foie gras—it was one of the best things I’ve ever tasted.[see below]

And a miniature brioche topped with micro-zest of lemon. Plus two breads, arriving with a bowl of olive oil and another bowl of aromatic oregano. One flavor is intended to enhance its partner, you combine them as you like.

And a miniature brioche topped with micro-zest of lemon. Plus two breads, arriving with a bowl of olive oil and another bowl of aromatic oregano. One flavor is intended to enhance its partner, you combine them as you like.

Then came a plate of gamba, a large prawn, sided by two basil-tinged green gnocchi draped with calamari crudo, plus a flash fried zucchini flower, on a little hill of broccolini. The gnocchi each sat on a brilliant green sauce of basil. This dish justified the entire trip to Paris.

Then came a plate of gamba, a large prawn, sided by two basil-tinged green gnocchi draped with calamari crudo, plus a flash fried zucchini flower, on a little hill of broccolini. The gnocchi each sat on a brilliant green sauce of basil. This dish justified the entire trip to Paris.

All flavors were robust yet unmuddied. Each ingredient made sense of the others, showing the chef’s intuitive understanding of how the dish would unfold as a process, rather than single creation of flavors combined in the kitchen. The center of the meal was a plate of duck encircled by warm cherries and a cherry mustard balsamic reduction. Adorned with tiny onion flowers. Yes it was terrific. But not as terrific as my dessert.

Arriving in two dishes was what amounted to a deconstructed tiramisu. As with all of this chef’s dishes, the dessert was intended to be enjoyed as a sequence, or layering of flavors.

Arriving in two dishes was what amounted to a deconstructed tiramisu. As with all of this chef’s dishes, the dessert was intended to be enjoyed as a sequence, or layering of flavors.

Mascarpone ice cream in one dish, candied orange peel on the side, and a warm baba drenched in rum on a crust of coffee nibs. Creme Chantilly on top was dusted with a veil of cacao and unidentifiable spices. I ate every bite. Finished with an espresso.

Mascarpone ice cream in one dish, candied orange peel on the side, and a warm baba drenched in rum on a crust of coffee nibs. Creme Chantilly on top was dusted with a veil of cacao and unidentifiable spices. I ate every bite. Finished with an espresso.

by Christina Waters | Nov 15, 2021 | Home, Movies |

Before I get down to serious ripping and shredding, I need to get this off my chest.

As a baby boomer, I read and thrilled to Frank Herbert‘s prescient, imaginative, and mythic futuristic novel. Canadian director Denis Villeneuve, of murky self-important Arrival fame, has taken it upon himself to launch an almost-three hour cinema version of Dune. This was an error of epic proportions. The badness of this film is the only thing close to epic in this exercise of cine-waste so awful, so clueless, so dis-inspired as to defy reason.

Villeneuve’s Dune is also murky, lethargic, impenetrable, and boring. What he has done to a seminal text should be illegal, like using the Holy Grail as a jello mold. All I could think, as I reeled out of the theater on a salt high, thanks to over-priced movie popcorn, was: how could I get back those three hours of my life?

Grab a sharp stick, aim it squarely at your left eye (or right, whatever you like) and stab! You will thus experience a more pleasurable sensation than that delivered by the clueless Canadian and his unpleasant cast.

Okay.

Now I can begin. I’ll start with the most egregious error made by this bloated production team: casting. It’s hard to recall casting this misguided, even hilarious, since that big blonde gentile Charlton Heston sauntered down the mountain with stone tablets in The Ten Commandments.

Starting with the worst: wasp-waisted Timothee Chalamet as the fierce, psychicically gifted messianic avatar Paul Atriedes. Chalamet would be fine in a bio-pic playing the young Oscar Wilde. Ideally in a film without any speaking parts. Chalamet was wretched as well as utterly unbelievable as the heir apparent to a powerful royal dynasty as well as leader of the new eco-desert utopia on Arakis. Yet, there might be five minutes of this almost 3-hour film in which the anorexic teen idol does not appear. He is so not up to the task that his mere presence inspires fantasies of the merely awful Kyle MacLachlen in David Lynch’s lackluster attempt to bring Dune to the screen 40 years earlier.

Maybe worse is the presence of Oscar Isaac. His mere presence on-screen is cause for genuine alarm, but to watch him attempt something like gravitas as Paul’s ill-fated father Duke Leto Atriedes is akin to enduring a three-hour root canal procedure. Does no one understand the importance of vocal power and nuance in filmmaking these days?

Rebecca Ferguson as Paul’s mother, the supernaturally trained Lady Jessica who teaches her son the special powers of her psychic order the Bene Gesserit, has an appropriately intelligent voice. We believe that she believes what she’s saying. Yet she, as all the others, is sabotaged again and again by a silly script.

And Josh Brolin as the adroit, amiable fight master Gurney Halleck? Not bloody likely. Brolin, with his Marine haircut and fatigues, looks like he stepped out of another film, and another timeline. He should have checked in with his acting coach before filming. So should Sharon Duncan-Brewster, who looks great as the double agent Shadout Mapes, but again, appears to have no working knowledge of the script, its language (English), or its meaning.

Another who needs slapping around is the once great Javier Bardem, a wooden cartoon of the mighty warrior of the desert tribe, the Fremen. All I could think of was Anthony Quinn as the Bedouin leader in Lawrence of Arabia. Quinn was more believable.

Here I’ll circle back on poor matinee-idol-du-jour Chalamet, who is burning through his fifteen minutes like an addict through fentanyl. So physically wraith-like and awkward as to mock the idea that he could match knives with the Fremen soldier who calls him out, Chalamet appears not to understand or care what he is doing. Indeed, he appears embarrassed to be in front of the camera, especially given the lingering closeups he has to endure. Is he Villeneuve’s fantasy boy?

I’m too exhausted to continue.

My next installment of Dune demolition will involve asking whether ponderous camerawork, massive explosions and a behemoth score can actually substitute for a script, dramatic tension, excitement, inspiration, and/or (god help us) acting.

to be continued…..

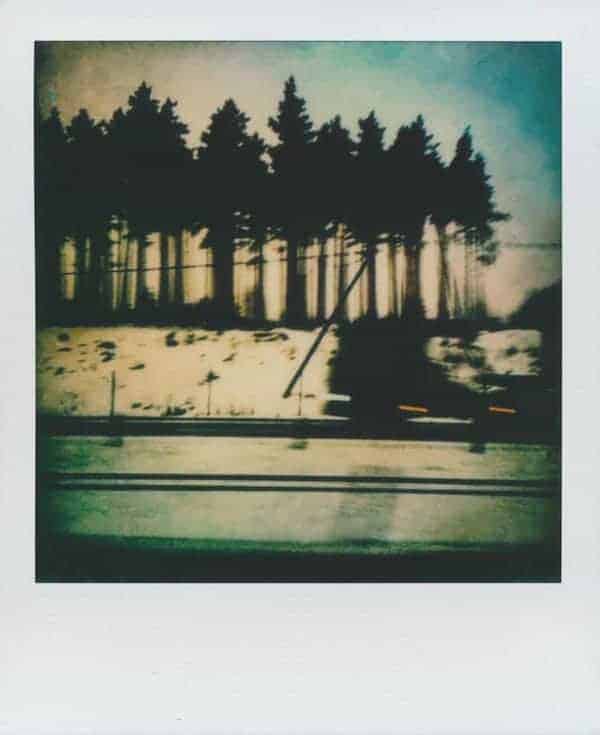

Northern Lights: Images from Per Forsström

by Christina Waters | Jul 28, 2020 | Home |

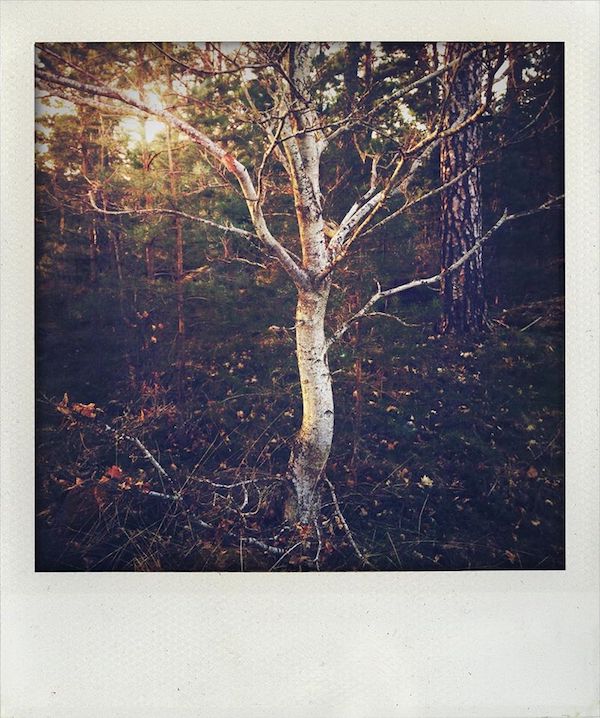

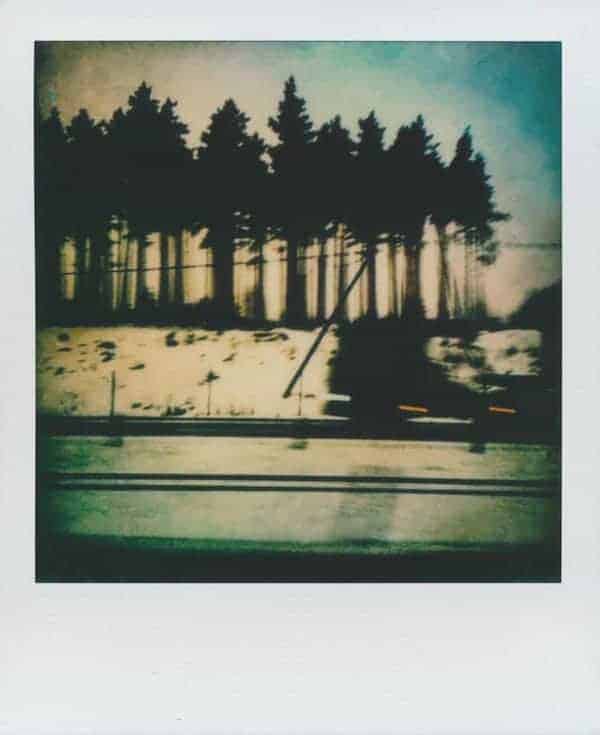

If Edvard Munch had been a photographer he might have been Per Forsström, a Stockholm-based new wave polaroid photographer whose growing oeuvre evokes the ambiguity of dreams. And like dreams, Forsström’s work is filled with seductive alliances between his skilled eye, Fate, and the richness of the unconscious.

I first saw his work on social media and was instantly hooked on the shimmering light and edginess of memory they seem to contain. The photographs are haunting. Often it’s the framing, the unexpected angles and sensitive composition. Most of these images are bathed in the soft focus and blurred margins of remembered summer afternoons. Certainly the artist’s manipulation of the famously viscous surface of Polaroid emulsion lends his work a fairytale quality. Reality that knows more than we realize.

Yet these are not pretty photographs in any clichéd sense. They are energized as much by the nordic noir of Henning Mankell and Jo Nesbo as they are by the midnight coves of Ingmar Bergman. I immediately felt a bond between the eternal regrets of Bergman’s finest films, Wild Strawberries for example, and the lonely forests Forsström clearly knows so well.

An art teacher in Stockholm, baby boomer Forsström grew up in the old Swedish university town of Lund. He drew, painted, dreamed of being a comic book artist, studied art in the University, and soon became a father. Carpentry, archaeology, taxi driving, he sampled many professions before settling in Stockholm to teach art. In 2013 he bought a camera, a Polaroid 360 with an electronic flash and “became obsessed.” Then he discovered the Impossible Project, an alliance of polaroid devotées with whom he shared a passion for experimental images. “I’m not at all interested in perfection technically speaking. That bores me to death.”

Which is why, in addition to polaroids and the refinements of an old school Hasselblad camera, Forsström works with the fixed focus challenges of the plastic Holga and Diana cameras.

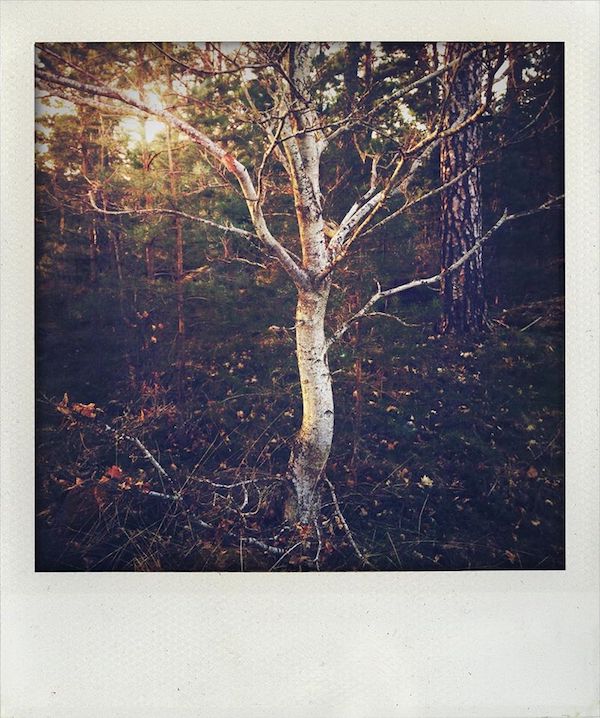

“I just happened to see this beautiful young oak tree as I was walking in the woods at the golden hour. It was something very gracious about it and I wanted to capture this tactile, dreamy almost unearthly graciousness.”

The beach scenes he captures reminded me of the place where I live, on the ocean, albeit one very distant from the Baltic Sea of Forsström’s images. On the beach—his beach, my beach, any beach— we revisit our childhoods, those summer holidays in which we could escape growing up. Where we remained forever young. Carefree, if we were lucky.

“To me the sandy beaches in the south of Sweden are almost unreal in the warm sunny summer days, long stretches of white sand, the stillness, the cold clear water, yes it’s dreamlike. Also the feeling of the blinding sunlight reflected in the water and the white sands, trying to evoke a feeling of all that, a drowsiness. Memories, yes, and you are helpless to them.”

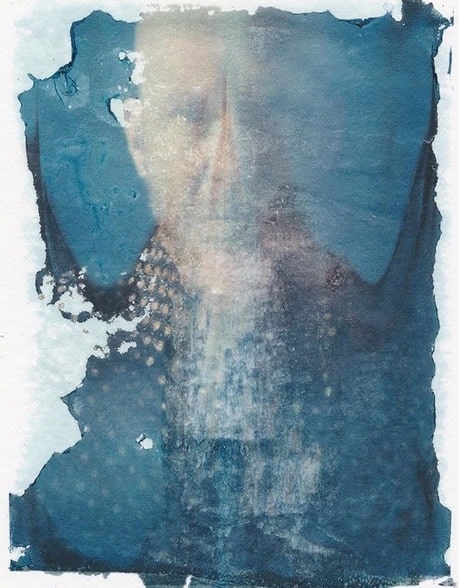

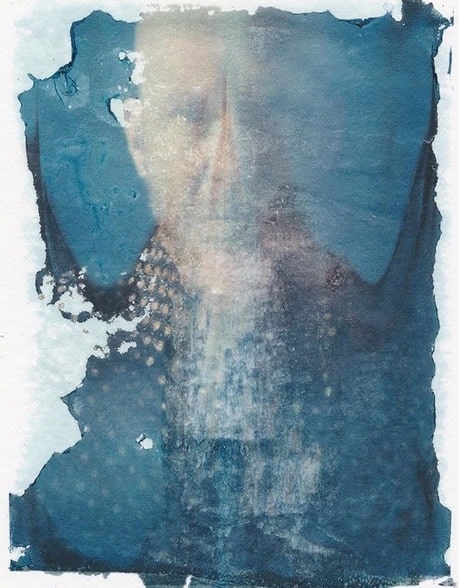

Such a rich and surprising picture. This one felt like a Baroque image, or perhaps a quiet moment in the studio of Velasquez, while he was painting Las Meninas. The smoky chiaroscuro seems to transcend the medium and displays the photographer’s visual instincts, combined with a variety of avant garde printing techniques. So deep are the darkest tones that we feel we can enter the picture plane and inhabit its various secrets and perfumes.

Forsström recalls making this photograph. “This self portrait comes from my love of Caravaggio and the chiaroscuro and of course Rembrandt. I shot this with a Hasselblad 501CM in bulb mode, experimenting with time and movement. I used no flash. I always try to have elements of uncertainty, a kind of disturbing nerve because that’s how I relate to the world.”

Forsström’s most seductive images take a few moments to become recognizable. Some, such as this mysterious faintly tinted picture, never quite reach resolution—much as a darkroom image might elude full disclosure.

But that’s their magic. They defy easy explanation. This one, with its soft focus edges and uncertain subject matter seems to lie just off shore. We can almost pull them in and make sense of them, but not quite. Like the most delicious and maddening dreams, they defy our grasp. And that is their power.

“The church in snow, it’s funny, I was just by chance driving past it. It had this magnetic aura, very old, Täby kyrka built in the 13th century. Inside there’s this famous wall painting by Albertus Pictor where Death plays chess with a poor mortal. This is the painting that inspired Ingmar Bergman in The Seventh Seal.”

This final image, a manipulated and distressed self-portrait, contains all the poetry of Forsström’s best pictures to date.

We see the artist, looking back at us, through many layers of dreams? years? memories? Like Alice, he seems to have slipped through the looking glass and now exists within mysteries beyond language. Only the puzzling textures suggest what he has seen. One suspects that the person we see through these layers of ink and chemicals is suspended in another world. Another time.

Per Forsström‘s photographs allow him the luxury of this rare and playful time travel. Perhaps these pieces are invitations to us, to join him.

Rusty and other tales of the Virus

by Christina Waters | Apr 12, 2020 | Home |

Rusty came on our walk this morning.

When you’re an adult women without children or pets, you name your hats. And your car, your plants, your pillows, even your laptop.

Rusty came from Switzerland, he’s red and woolly and sits strangely on my small head.

Still he has had a colorful life thus far. Rusty was born in San Gallen, near the Italian border where we went for New Year’s after spending Christmas in Bologna. The year after the turn of the millennium.

He experienced his first snow on New Year’s Day and has since come with me to Death Valley, also at New Year’s, and to the Mojave, and England, and along the Pogonip Trail in rainy winter weather.

My four pomegranate seedlings—now almost 5 years old—are named Pom, Pom-Pom, Pometto, and Pompeo. It took us a full year just to remember which was which. But they liked having names and responded to being given such attention. Now they are quite large.

Grape, my purple velour throw pillow, has been with me for 40 years, with two changes of stuffing, six changes of men, and several major mendings.

Life is tastier when beloved objects have names. They become part of your life in an intimate way. They become persons. You expand yourself in unexpected ways through your companion pillows, plants, clothing, and special mementos.

I can’t imagine the poverty of a life containing only things, objects, rather than special friends and identifiable companions. I might be odd, but there it is.

The more I love my named entities, the harder it becomes to let them go. They become irreplaceable, far from being stuff you can exchange for newer stuff, or cleaner stuff without so many stains.

Think of your favorite sweater. It’s not perfect. It has stains, it has holes, it’s been mended. A lot.

Yet these are not good enough reasons to let it go. Au contraire. Each sign of weathering shows how much your have worn it, how far it has traveled with you. Your life is contained within its seams and stitching.

Just touching Grape brings back memories of times when I lived in a patchouli-scented log cabin in the woods. No money, no vintage wines, just elderflower tea and hash.

When I wear Rusty I can smell the snow of New Year’s Day in Switzerland.

Of course it’s neurotic to live this way. Also rich and joyful.

Oscars 2020: A few choice remarks

by Christina Waters | Feb 7, 2020 | Home |

Yes, Brad Pitt should win the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his deceptively casual turn in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time In ….Hollywood. A fairytale about the way movies were, or might have been made, with a fairytale ending. A “just so” story that takes one of the meatiest horror stories in mid-20th century America—the true life massacre of Sharan Tate et al. by the Manson Family—and massages it until it implodes into a magic realist ending. Oh the horror is still there, but not where we expect it.

The cool thing about Pitt’s performance is its maturity, utter confidence, and delicious surprise. Oh we knew he had the stuff back when his mind came loose in 12 Monkeys, and when he left it all on the floor in Fight Club. But then we lost sight of that Brad Pitt, and replaced him with Angelina Jolie’s arm candy. We did what some male chauvinists do to women—we dismissed him as simply an object. A dreamy one, to be sure. But still an object.

Well, director Tarantino remembered the actor slumbering under all that Armani, and that’s the guy who turned up to match wits and instincts with Leo DiCaprio in Tarantino’s film.

My pick for Best Actor is the astonishing Antonio Banderas who probably doesn’t have a chance because the Academy likes over the top chew the chandeliers performances like Joaquin Phoenix in The Joker. Phoenix will win, but Banderas was flawless—flawless, exposed, and touching as director Almadovar’s surrogate in a beautiful film, Pain and Glory.

As for Best Actress, frankly I’m at a loss. I didn’t see all of the nominees this year, between failure of films to appeal to me and having hand surgery, it wasn’t my most movie-filled year. I DO know that the ultra-camp, unconvincing Renée Zellweger (who’s sure to win, apparently) should not win. She was in my opinion grotesque as the divine and vulnerable Judy Garland. Just silly drag stuff and she sang Judy’s songs!!! Perhaps she should win for the chutzpah to cover one of the great singers of the American songbook.

And while I adore Saoirse Ronan, this wasn’t her best outing either.

In fact, I’ll go further and buck the critical tide: I wasn’t as impressed with Greta Gerwig’s ambitious revival of Little Women as I’d hoped to be. It felt too contrived, almost Hallmarkean in its earnest faithfulness to the period. I also thought there was a lot of miscasting in Gerwig’s film. Timothée Chalamet was too fragile to be believed, and Florence Pugh was too modern and mature to be credible as the younger sister.

In the Supporting Actor category, Pitt’s competition is pretty powerful I gotta say. I mean who doesn’t love the colossal Tom Hanks? Al Pacino and Joe Pesci will probably cancel each other out and the day Anthony Hopkins convinces me that he’s a pope…..So I’m still with Brad Pitt for Supporting Actor.

As for Best Supporting Actress. Full disclosure: I did not see Marriage Story, which at first I didn’t even want to see, and then when I became intrigued, had already left town. But given Laura Dern’s mastery of every role she’s ever played, she might just take this one. On the other hand, Kathy Bates is god. So….up for grabs.

Best Director? Well if Sam Mendes doesn’t win for 1917, then it should go to Bong Joon Ho whose brilliant urban myth Parasite shattered all kinds of conventions, styles, and expectations.

Best Picture? Again, I didn’t see most of the entries, but given the recent awards thrown at 1917, it seems quite likely that Sam Mendes’

haunting study of the young men who fought “over there” could take it. But it really should go to Bong Joon Ho, whose film remains one of the finest most complex I’ve seen in a decade. Any decade.

Next morning, reserved ticket in hand (or rather on my phone) I was ushered into a very short line (three people!) into the vastness of the Louvre. Avoiding the crowded line encircling the Mona Lisa, I instead re-visited a few of my favorite paintings, including a Mantegna that might have been painted yesterday, the miraculous Virgin of the Rocks, and rediscovered the genius of Jean-Louis David.

Next morning, reserved ticket in hand (or rather on my phone) I was ushered into a very short line (three people!) into the vastness of the Louvre. Avoiding the crowded line encircling the Mona Lisa, I instead re-visited a few of my favorite paintings, including a Mantegna that might have been painted yesterday, the miraculous Virgin of the Rocks, and rediscovered the genius of Jean-Louis David. I devoured as much as I could before visual saturation set in and it was time to head up the street to Bistrot Victoires for a delicious duck confit with perfect potatoes and a glass of Côtes du Rhône.

I devoured as much as I could before visual saturation set in and it was time to head up the street to Bistrot Victoires for a delicious duck confit with perfect potatoes and a glass of Côtes du Rhône. Followed by an espresso, the lunch confirmed my belief in Paris as a city of high culinary standards.

Followed by an espresso, the lunch confirmed my belief in Paris as a city of high culinary standards.

That evening, I walked across the river again to the exquisite Gothic jewelbox that is Saint Chapelle, built by St. Louis to house his splinter of the True Cross, and enjoyed the rare experience of an intimate concert of piano music by the heroic performer Vanessa Wagner, a woman with Bronzino arms and complete command of her instrument.

That evening, I walked across the river again to the exquisite Gothic jewelbox that is Saint Chapelle, built by St. Louis to house his splinter of the True Cross, and enjoyed the rare experience of an intimate concert of piano music by the heroic performer Vanessa Wagner, a woman with Bronzino arms and complete command of her instrument. Only two hundred seats in the tiny upper sanctuary, still light enough at 8pm for sun to illuminate the incredible stained glass, as we listened to Mozart, Rachmaninoff, and Debussy. Acoustics as impeccable as the interior itself.

Only two hundred seats in the tiny upper sanctuary, still light enough at 8pm for sun to illuminate the incredible stained glass, as we listened to Mozart, Rachmaninoff, and Debussy. Acoustics as impeccable as the interior itself.

The initial amuses dishes included a single deep-fried pastry pillow filled with a warm quail egg yolk. A little pastry boat filled with fresh pea puree, topped with a tangle of mâche and parmesan. A pretty salad of warm grapes and tiny beets arrived topped with a scoop of creamy feta in a pool of sweet and salty broth. And an incredible cheese straw (much more elegant than that) but essentially a finger of crisp cheese filled with veloté of foie gras—it was one of the best things I’ve ever tasted.[see below]

The initial amuses dishes included a single deep-fried pastry pillow filled with a warm quail egg yolk. A little pastry boat filled with fresh pea puree, topped with a tangle of mâche and parmesan. A pretty salad of warm grapes and tiny beets arrived topped with a scoop of creamy feta in a pool of sweet and salty broth. And an incredible cheese straw (much more elegant than that) but essentially a finger of crisp cheese filled with veloté of foie gras—it was one of the best things I’ve ever tasted.[see below] And a miniature brioche topped with micro-zest of lemon. Plus two breads, arriving with a bowl of olive oil and another bowl of aromatic oregano. One flavor is intended to enhance its partner, you combine them as you like.

And a miniature brioche topped with micro-zest of lemon. Plus two breads, arriving with a bowl of olive oil and another bowl of aromatic oregano. One flavor is intended to enhance its partner, you combine them as you like. Then came a plate of gamba, a large prawn, sided by two basil-tinged green gnocchi draped with calamari crudo, plus a flash fried zucchini flower, on a little hill of broccolini. The gnocchi each sat on a brilliant green sauce of basil. This dish justified the entire trip to Paris.

Then came a plate of gamba, a large prawn, sided by two basil-tinged green gnocchi draped with calamari crudo, plus a flash fried zucchini flower, on a little hill of broccolini. The gnocchi each sat on a brilliant green sauce of basil. This dish justified the entire trip to Paris. Arriving in two dishes was what amounted to a deconstructed tiramisu. As with all of this chef’s dishes, the dessert was intended to be enjoyed as a sequence, or layering of flavors.

Arriving in two dishes was what amounted to a deconstructed tiramisu. As with all of this chef’s dishes, the dessert was intended to be enjoyed as a sequence, or layering of flavors. Mascarpone ice cream in one dish, candied orange peel on the side, and a warm baba drenched in rum on a crust of coffee nibs. Creme Chantilly on top was dusted with a veil of cacao and unidentifiable spices. I ate every bite. Finished with an espresso.

Mascarpone ice cream in one dish, candied orange peel on the side, and a warm baba drenched in rum on a crust of coffee nibs. Creme Chantilly on top was dusted with a veil of cacao and unidentifiable spices. I ate every bite. Finished with an espresso.