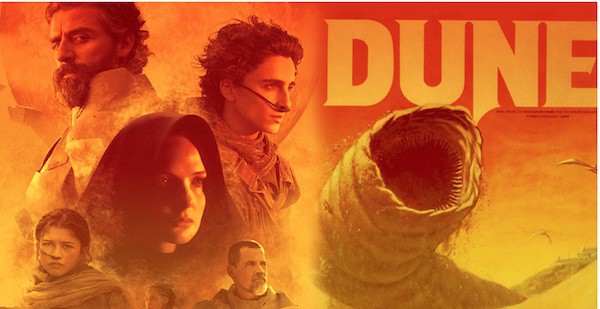

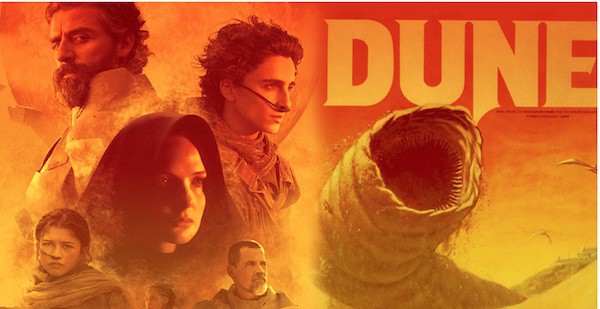

by Christina Waters | Nov 15, 2021 | Home, Movies |

Before I get down to serious ripping and shredding, I need to get this off my chest.

As a baby boomer, I read and thrilled to Frank Herbert‘s prescient, imaginative, and mythic futuristic novel. Canadian director Denis Villeneuve, of murky self-important Arrival fame, has taken it upon himself to launch an almost-three hour cinema version of Dune. This was an error of epic proportions. The badness of this film is the only thing close to epic in this exercise of cine-waste so awful, so clueless, so dis-inspired as to defy reason.

Villeneuve’s Dune is also murky, lethargic, impenetrable, and boring. What he has done to a seminal text should be illegal, like using the Holy Grail as a jello mold. All I could think, as I reeled out of the theater on a salt high, thanks to over-priced movie popcorn, was: how could I get back those three hours of my life?

Grab a sharp stick, aim it squarely at your left eye (or right, whatever you like) and stab! You will thus experience a more pleasurable sensation than that delivered by the clueless Canadian and his unpleasant cast.

Okay.

Now I can begin. I’ll start with the most egregious error made by this bloated production team: casting. It’s hard to recall casting this misguided, even hilarious, since that big blonde gentile Charlton Heston sauntered down the mountain with stone tablets in The Ten Commandments.

Starting with the worst: wasp-waisted Timothee Chalamet as the fierce, psychicically gifted messianic avatar Paul Atriedes. Chalamet would be fine in a bio-pic playing the young Oscar Wilde. Ideally in a film without any speaking parts. Chalamet was wretched as well as utterly unbelievable as the heir apparent to a powerful royal dynasty as well as leader of the new eco-desert utopia on Arakis. Yet, there might be five minutes of this almost 3-hour film in which the anorexic teen idol does not appear. He is so not up to the task that his mere presence inspires fantasies of the merely awful Kyle MacLachlen in David Lynch’s lackluster attempt to bring Dune to the screen 40 years earlier.

Maybe worse is the presence of Oscar Isaac. His mere presence on-screen is cause for genuine alarm, but to watch him attempt something like gravitas as Paul’s ill-fated father Duke Leto Atriedes is akin to enduring a three-hour root canal procedure. Does no one understand the importance of vocal power and nuance in filmmaking these days?

Rebecca Ferguson as Paul’s mother, the supernaturally trained Lady Jessica who teaches her son the special powers of her psychic order the Bene Gesserit, has an appropriately intelligent voice. We believe that she believes what she’s saying. Yet she, as all the others, is sabotaged again and again by a silly script.

And Josh Brolin as the adroit, amiable fight master Gurney Halleck? Not bloody likely. Brolin, with his Marine haircut and fatigues, looks like he stepped out of another film, and another timeline. He should have checked in with his acting coach before filming. So should Sharon Duncan-Brewster, who looks great as the double agent Shadout Mapes, but again, appears to have no working knowledge of the script, its language (English), or its meaning.

Another who needs slapping around is the once great Javier Bardem, a wooden cartoon of the mighty warrior of the desert tribe, the Fremen. All I could think of was Anthony Quinn as the Bedouin leader in Lawrence of Arabia. Quinn was more believable.

Here I’ll circle back on poor matinee-idol-du-jour Chalamet, who is burning through his fifteen minutes like an addict through fentanyl. So physically wraith-like and awkward as to mock the idea that he could match knives with the Fremen soldier who calls him out, Chalamet appears not to understand or care what he is doing. Indeed, he appears embarrassed to be in front of the camera, especially given the lingering closeups he has to endure. Is he Villeneuve’s fantasy boy?

I’m too exhausted to continue.

My next installment of Dune demolition will involve asking whether ponderous camerawork, massive explosions and a behemoth score can actually substitute for a script, dramatic tension, excitement, inspiration, and/or (god help us) acting.

to be continued…..

Northern Lights: Images from Per Forsström

by Christina Waters | Jul 28, 2020 | Home |

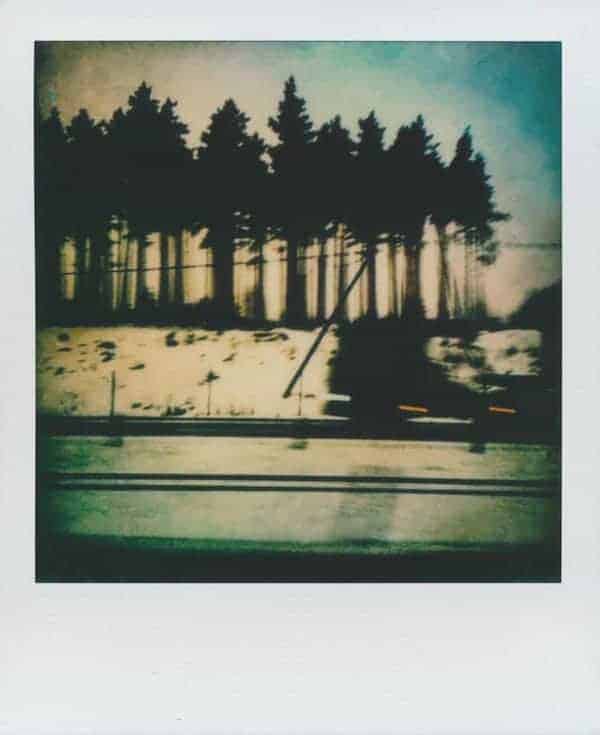

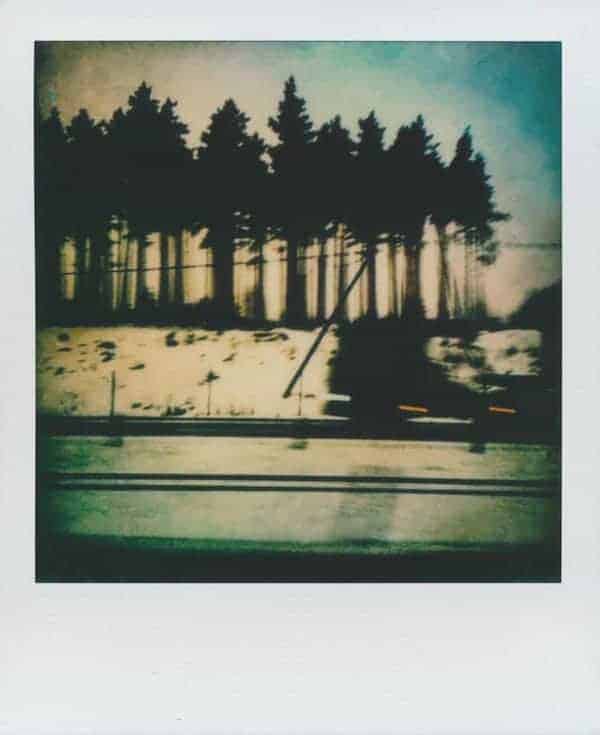

If Edvard Munch had been a photographer he might have been Per Forsström, a Stockholm-based new wave polaroid photographer whose growing oeuvre evokes the ambiguity of dreams. And like dreams, Forsström’s work is filled with seductive alliances between his skilled eye, Fate, and the richness of the unconscious.

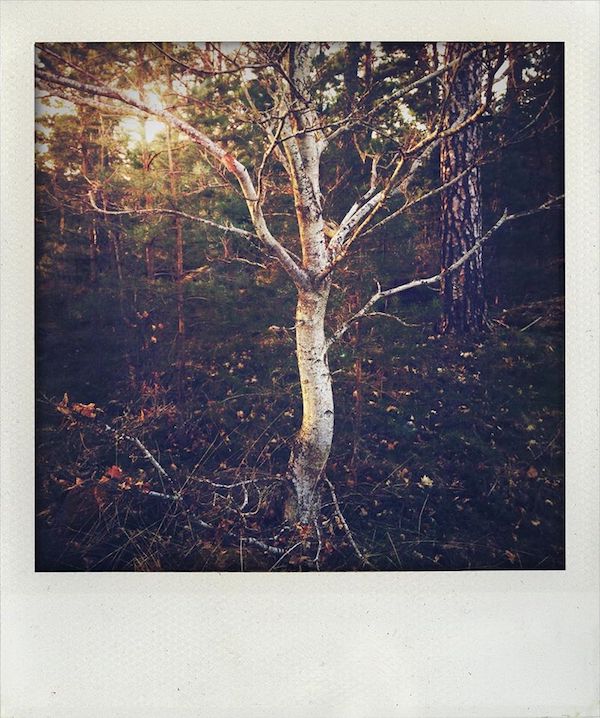

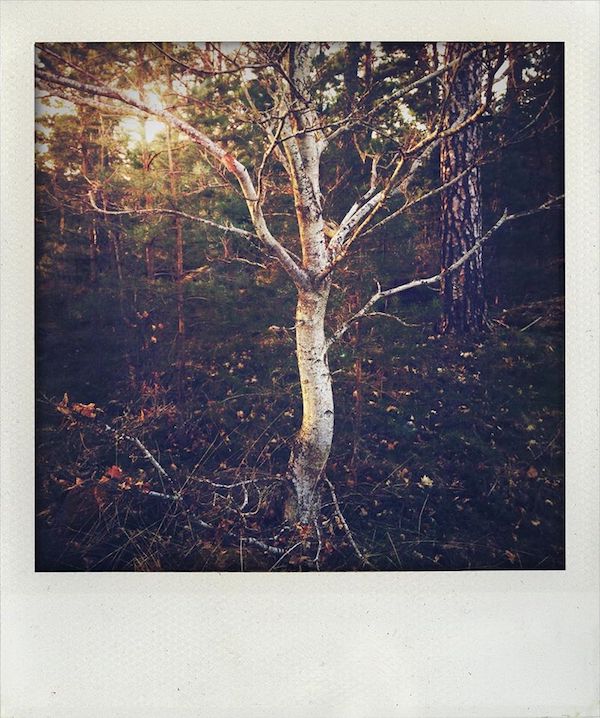

I first saw his work on social media and was instantly hooked on the shimmering light and edginess of memory they seem to contain. The photographs are haunting. Often it’s the framing, the unexpected angles and sensitive composition. Most of these images are bathed in the soft focus and blurred margins of remembered summer afternoons. Certainly the artist’s manipulation of the famously viscous surface of Polaroid emulsion lends his work a fairytale quality. Reality that knows more than we realize.

Yet these are not pretty photographs in any clichéd sense. They are energized as much by the nordic noir of Henning Mankell and Jo Nesbo as they are by the midnight coves of Ingmar Bergman. I immediately felt a bond between the eternal regrets of Bergman’s finest films, Wild Strawberries for example, and the lonely forests Forsström clearly knows so well.

An art teacher in Stockholm, baby boomer Forsström grew up in the old Swedish university town of Lund. He drew, painted, dreamed of being a comic book artist, studied art in the University, and soon became a father. Carpentry, archaeology, taxi driving, he sampled many professions before settling in Stockholm to teach art. In 2013 he bought a camera, a Polaroid 360 with an electronic flash and “became obsessed.” Then he discovered the Impossible Project, an alliance of polaroid devotées with whom he shared a passion for experimental images. “I’m not at all interested in perfection technically speaking. That bores me to death.”

Which is why, in addition to polaroids and the refinements of an old school Hasselblad camera, Forsström works with the fixed focus challenges of the plastic Holga and Diana cameras.

“I just happened to see this beautiful young oak tree as I was walking in the woods at the golden hour. It was something very gracious about it and I wanted to capture this tactile, dreamy almost unearthly graciousness.”

The beach scenes he captures reminded me of the place where I live, on the ocean, albeit one very distant from the Baltic Sea of Forsström’s images. On the beach—his beach, my beach, any beach— we revisit our childhoods, those summer holidays in which we could escape growing up. Where we remained forever young. Carefree, if we were lucky.

“To me the sandy beaches in the south of Sweden are almost unreal in the warm sunny summer days, long stretches of white sand, the stillness, the cold clear water, yes it’s dreamlike. Also the feeling of the blinding sunlight reflected in the water and the white sands, trying to evoke a feeling of all that, a drowsiness. Memories, yes, and you are helpless to them.”

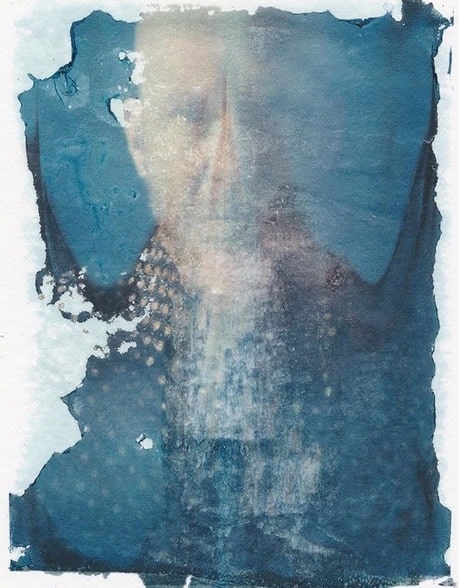

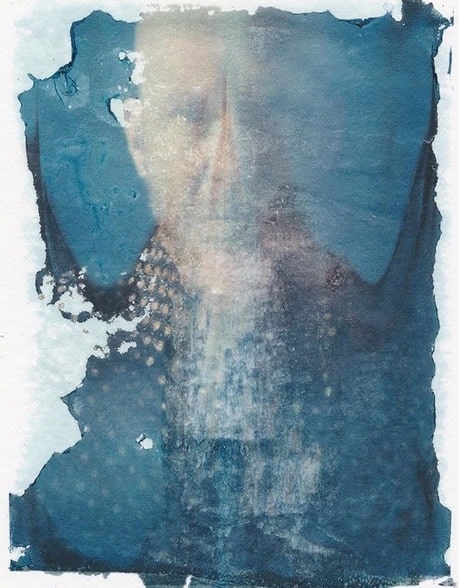

Such a rich and surprising picture. This one felt like a Baroque image, or perhaps a quiet moment in the studio of Velasquez, while he was painting Las Meninas. The smoky chiaroscuro seems to transcend the medium and displays the photographer’s visual instincts, combined with a variety of avant garde printing techniques. So deep are the darkest tones that we feel we can enter the picture plane and inhabit its various secrets and perfumes.

Forsström recalls making this photograph. “This self portrait comes from my love of Caravaggio and the chiaroscuro and of course Rembrandt. I shot this with a Hasselblad 501CM in bulb mode, experimenting with time and movement. I used no flash. I always try to have elements of uncertainty, a kind of disturbing nerve because that’s how I relate to the world.”

Forsström’s most seductive images take a few moments to become recognizable. Some, such as this mysterious faintly tinted picture, never quite reach resolution—much as a darkroom image might elude full disclosure.

But that’s their magic. They defy easy explanation. This one, with its soft focus edges and uncertain subject matter seems to lie just off shore. We can almost pull them in and make sense of them, but not quite. Like the most delicious and maddening dreams, they defy our grasp. And that is their power.

“The church in snow, it’s funny, I was just by chance driving past it. It had this magnetic aura, very old, Täby kyrka built in the 13th century. Inside there’s this famous wall painting by Albertus Pictor where Death plays chess with a poor mortal. This is the painting that inspired Ingmar Bergman in The Seventh Seal.”

This final image, a manipulated and distressed self-portrait, contains all the poetry of Forsström’s best pictures to date.

We see the artist, looking back at us, through many layers of dreams? years? memories? Like Alice, he seems to have slipped through the looking glass and now exists within mysteries beyond language. Only the puzzling textures suggest what he has seen. One suspects that the person we see through these layers of ink and chemicals is suspended in another world. Another time.

Per Forsström‘s photographs allow him the luxury of this rare and playful time travel. Perhaps these pieces are invitations to us, to join him.

Rusty and other tales of the Virus

by Christina Waters | Apr 12, 2020 | Home |

Rusty came on our walk this morning.

When you’re an adult women without children or pets, you name your hats. And your car, your plants, your pillows, even your laptop.

Rusty came from Switzerland, he’s red and woolly and sits strangely on my small head.

Still he has had a colorful life thus far. Rusty was born in San Gallen, near the Italian border where we went for New Year’s after spending Christmas in Bologna. The year after the turn of the millennium.

He experienced his first snow on New Year’s Day and has since come with me to Death Valley, also at New Year’s, and to the Mojave, and England, and along the Pogonip Trail in rainy winter weather.

My four pomegranate seedlings—now almost 5 years old—are named Pom, Pom-Pom, Pometto, and Pompeo. It took us a full year just to remember which was which. But they liked having names and responded to being given such attention. Now they are quite large.

Grape, my purple velour throw pillow, has been with me for 40 years, with two changes of stuffing, six changes of men, and several major mendings.

Life is tastier when beloved objects have names. They become part of your life in an intimate way. They become persons. You expand yourself in unexpected ways through your companion pillows, plants, clothing, and special mementos.

I can’t imagine the poverty of a life containing only things, objects, rather than special friends and identifiable companions. I might be odd, but there it is.

The more I love my named entities, the harder it becomes to let them go. They become irreplaceable, far from being stuff you can exchange for newer stuff, or cleaner stuff without so many stains.

Think of your favorite sweater. It’s not perfect. It has stains, it has holes, it’s been mended. A lot.

Yet these are not good enough reasons to let it go. Au contraire. Each sign of weathering shows how much your have worn it, how far it has traveled with you. Your life is contained within its seams and stitching.

Just touching Grape brings back memories of times when I lived in a patchouli-scented log cabin in the woods. No money, no vintage wines, just elderflower tea and hash.

When I wear Rusty I can smell the snow of New Year’s Day in Switzerland.

Of course it’s neurotic to live this way. Also rich and joyful.

Oscars 2020: A few choice remarks

by Christina Waters | Feb 7, 2020 | Home |

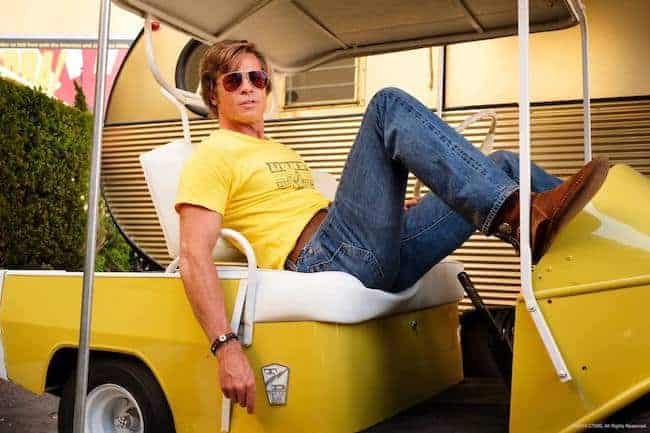

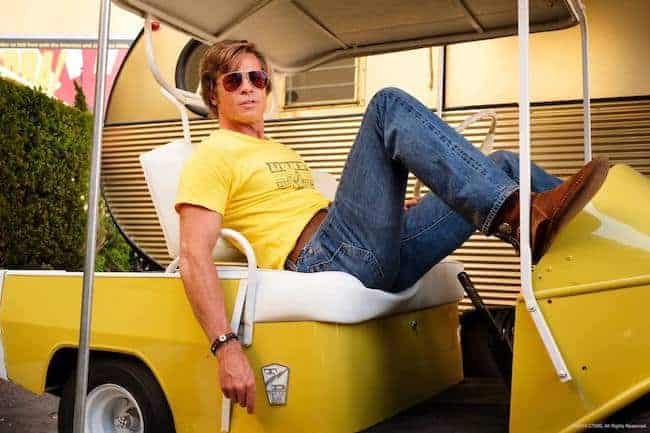

Yes, Brad Pitt should win the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his deceptively casual turn in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time In ….Hollywood. A fairytale about the way movies were, or might have been made, with a fairytale ending. A “just so” story that takes one of the meatiest horror stories in mid-20th century America—the true life massacre of Sharan Tate et al. by the Manson Family—and massages it until it implodes into a magic realist ending. Oh the horror is still there, but not where we expect it.

The cool thing about Pitt’s performance is its maturity, utter confidence, and delicious surprise. Oh we knew he had the stuff back when his mind came loose in 12 Monkeys, and when he left it all on the floor in Fight Club. But then we lost sight of that Brad Pitt, and replaced him with Angelina Jolie’s arm candy. We did what some male chauvinists do to women—we dismissed him as simply an object. A dreamy one, to be sure. But still an object.

Well, director Tarantino remembered the actor slumbering under all that Armani, and that’s the guy who turned up to match wits and instincts with Leo DiCaprio in Tarantino’s film.

My pick for Best Actor is the astonishing Antonio Banderas who probably doesn’t have a chance because the Academy likes over the top chew the chandeliers performances like Joaquin Phoenix in The Joker. Phoenix will win, but Banderas was flawless—flawless, exposed, and touching as director Almadovar’s surrogate in a beautiful film, Pain and Glory.

As for Best Actress, frankly I’m at a loss. I didn’t see all of the nominees this year, between failure of films to appeal to me and having hand surgery, it wasn’t my most movie-filled year. I DO know that the ultra-camp, unconvincing Renée Zellweger (who’s sure to win, apparently) should not win. She was in my opinion grotesque as the divine and vulnerable Judy Garland. Just silly drag stuff and she sang Judy’s songs!!! Perhaps she should win for the chutzpah to cover one of the great singers of the American songbook.

And while I adore Saoirse Ronan, this wasn’t her best outing either.

In fact, I’ll go further and buck the critical tide: I wasn’t as impressed with Greta Gerwig’s ambitious revival of Little Women as I’d hoped to be. It felt too contrived, almost Hallmarkean in its earnest faithfulness to the period. I also thought there was a lot of miscasting in Gerwig’s film. Timothée Chalamet was too fragile to be believed, and Florence Pugh was too modern and mature to be credible as the younger sister.

In the Supporting Actor category, Pitt’s competition is pretty powerful I gotta say. I mean who doesn’t love the colossal Tom Hanks? Al Pacino and Joe Pesci will probably cancel each other out and the day Anthony Hopkins convinces me that he’s a pope…..So I’m still with Brad Pitt for Supporting Actor.

As for Best Supporting Actress. Full disclosure: I did not see Marriage Story, which at first I didn’t even want to see, and then when I became intrigued, had already left town. But given Laura Dern’s mastery of every role she’s ever played, she might just take this one. On the other hand, Kathy Bates is god. So….up for grabs.

Best Director? Well if Sam Mendes doesn’t win for 1917, then it should go to Bong Joon Ho whose brilliant urban myth Parasite shattered all kinds of conventions, styles, and expectations.

Best Picture? Again, I didn’t see most of the entries, but given the recent awards thrown at 1917, it seems quite likely that Sam Mendes’

haunting study of the young men who fought “over there” could take it. But it really should go to Bong Joon Ho, whose film remains one of the finest most complex I’ve seen in a decade. Any decade.

Parasite: a 21st Century Fable

by Christina Waters | Nov 15, 2019 | Art, Home |

Parasite, the new film by Korean auteur director Bong Joon Ho, is not only gorgeous to look at, it presents a harrowing satire on the state of class inequity in the 21st century. It’s hard to think of a recent film that packs this much metaphorical power. Set in Korea in the midst of a Dickensian disparity of wealth—the Kims live in basement squalor, the Parks live in upscale serenity. But it could be anywhere in the first world. It is here, right now, and that very fact provides the razor edge of recognition audiences feel in response to this darkly comic/existential romp that snatched the Cannes Festival’s Palme d’Or away from Quentin Tarantino (See my review of Tarantino’s “Once upon a time in Hollywood”.)

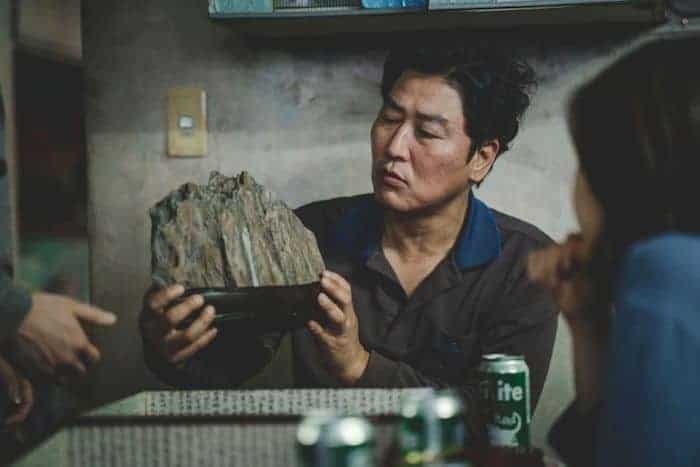

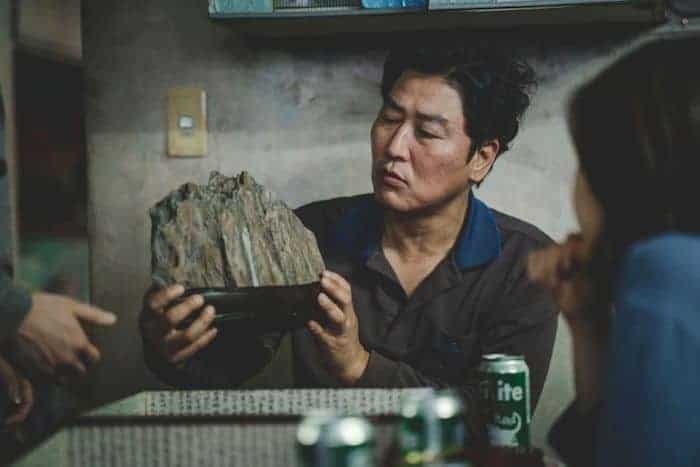

Parasite is a tale told through two families: the luckless, unemployed Kim Family headed by the extraordinary Kang-Ho Song as the father, Kim Chung-Sook as his wife, Choi Woo-Shik as teenaged son “Kevin” and Park So-Dam as his crafty hacker sister “Jessica. Determined to claw their way out of their ghetto squalor, the Kims scheme their way (I won’t spoil it) into the lives of the wealthy Park Family, led by Cho Yeo-jeong as the naive, lovely Mrs. Park and Lee Sun Gyun as style-conscious CEO Mr. Park.

Before you know it the Kims, who’ll literally do anything to make money, manage to insinuate themselves into the heart of the Park’s splendid household. It is a symbiotic ecosystem made in the hellishly brilliant imagination of this director.

Before you know it the Kims, who’ll literally do anything to make money, manage to insinuate themselves into the heart of the Park’s splendid household. It is a symbiotic ecosystem made in the hellishly brilliant imagination of this director.

[Above we find the resourceful Kim siblings finding the best signal from their neighbor’s wifi right above the toilet.]

Mr. Kim becomes Mr. Park’s driver, Mrs. Kim is the new Park housekeeper after cleverly managing to get the former one fired (the scenes here are laugh out loud funny). The son becomes tutor (and lover) to the Park’s daughter, and his sister poses as an art therapist for the Park’s young son, who is obsessed with American Indians.

The house itself is a key player in what will reveal itself to be Bong’s sly-handed tale of social inequity. An architectural masterpiece (designed by director Bong and made especially for the film) the sleek modernist house is laid out in interlocking levels. The living room’s enormous wall of glass overlooks an oasis of green lawn bordered by a manicured hedge.

The house itself is a key player in what will reveal itself to be Bong’s sly-handed tale of social inequity. An architectural masterpiece (designed by director Bong and made especially for the film) the sleek modernist house is laid out in interlocking levels. The living room’s enormous wall of glass overlooks an oasis of green lawn bordered by a manicured hedge.  This hermetic world insulates the Parks from any unsightly social reality and makes a painful contrast to the mess and chaos of the Kim’s basement apartment. Most importantly to the director’s storytelling, the house also contains a secret passage into yet another domain—and a ghastly secret buried deep within the heart of lavish wealth.

This hermetic world insulates the Parks from any unsightly social reality and makes a painful contrast to the mess and chaos of the Kim’s basement apartment. Most importantly to the director’s storytelling, the house also contains a secret passage into yet another domain—and a ghastly secret buried deep within the heart of lavish wealth.

Bong’s social commentary is never heavy handed, but it spares no one.

How this secret is discovered, what it contains, and where its layered metaphors lead are the elements driving a tsunami of loss, compassion, violence, joy, and ultimately a fairytale ending.

Parasite is powered by poetic cinematography, scored with Western classical music (another edgy dig at Korean social pretentions) and acted by a cast of brilliant players as capable of slapstick as heartbreak. I laughed my way through this film, even during its most terrifying scenes. The two families and the social codes they embody are turned inside out more than once, and never in predictable ways. All the actors are memorable, but especially lead player Kang-Ho Song, Mr. Kim [above], a frequent Bong collaborator. His broad face is roadmap of dashed dreams. As expressive as any Willem Dafoe, a savage/tender mirror reflecting Mr. Kim’s transformation—and his realization that his family’s larceny has triggered untold psychic damage. Nothing in Mr. Kim’s life has ever worked out, and Song’s face ultimately reveals despair on a Kierkegaardian scale. A great actor in a part worthy of his astonishing gifts.

Near the end of Parasite we find that just desserts are the main course of an outdoor birthday party for the spoiled Park son.  And once the shocking visual pyrotechnics have cooled down, the film draws to a haunting, eloquent close a la Charles Dickens. Desperate and ephemeral dreams, of the sort that reveal how much the rich and the poor are mutually bound in a slow dance of need, greed, hypocrisy, and desire.

And once the shocking visual pyrotechnics have cooled down, the film draws to a haunting, eloquent close a la Charles Dickens. Desperate and ephemeral dreams, of the sort that reveal how much the rich and the poor are mutually bound in a slow dance of need, greed, hypocrisy, and desire.

Parasite is a stunning cinematic fable, brilliant in every way, and for my money….unforgettable.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood

by Christina Waters | Aug 4, 2019 | Home |

The title of Quentin Tarantino’s ninth film is significant. Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood. This is how fairytales begin: once upon a time. Something to keep in mind as you watch this juicy look in the rearview mirror at the days when Hollywood films were long on cleavage, polyester, and cowboys with sideburns.

Acid rock competed with the Beatles, Beach Boys and Sly & the Family Stone. Everybody smoked. And marijuana was in its first ascendance. Let me repeat that—everyone smokes in this film. All.The.Time. Which of course was the way it was. Watching the actors smoke amounts to a risk-free contact high.

A lot of things happened in the summer of 1969, and setting foot on the moon was only one of them.

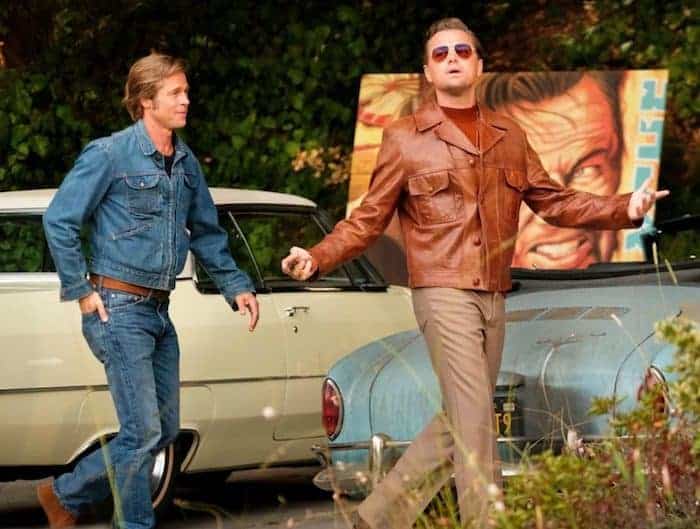

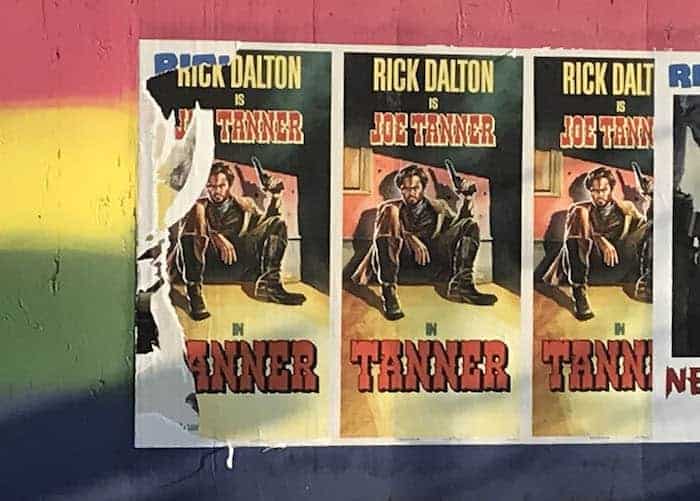

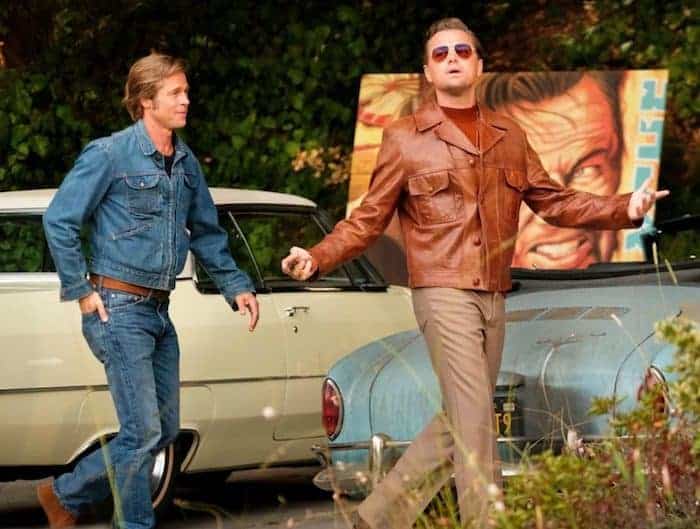

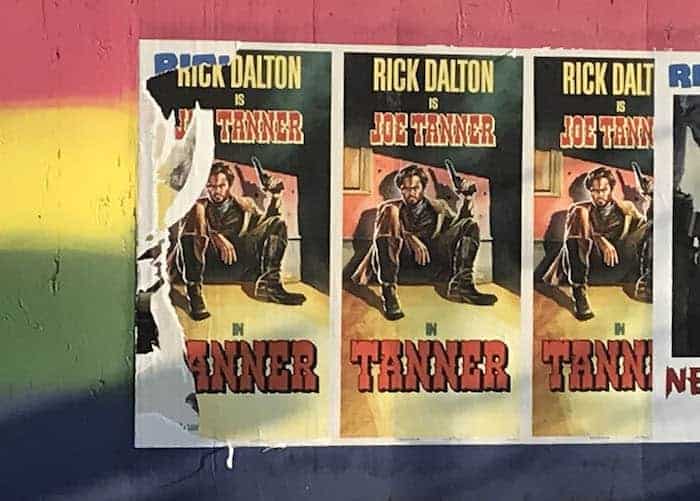

In Hollywood we meet fading TV star Rick Dalton (Leonardo diCaprio) and his faithful stunt double Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt). Dalton, once the star of his own series, is now reduced to picking up work as the bad guy in B grade Westerns and is desperate to keep his career from sinking further into the toilet. He’s lost his license (too many DUIs) and has to be driven by Booth, who is also his best buddy and all-around gofer. They cruise the canyons in Dalton’s 1966 pale yellow Cadillac deVille down the winding roads like a couple of Neal Cassidys, radio blasting, six-pack at the ready.

But things are changing in the movie industry, as the actor, his stuntman, and director Tarantino all mourn. TV is winning, producer’s agendas have become good guy/bad guy deal-making, and it’s no longer the Golden Age of John Wayne and film noir detective thrillers. Dalton needs some serious career counseling, which he gets from a hustler agent Marvin Schwarz, Al Pacino in a delightfully woeful wig. Kid, he’s told, you’re taking guest slots in too many Westernsas the bad guy, the guy who always gets beaten in the gun fight. You keep getting beaten, and people will begin to see you as a loser.

Dalton gets it, and starts examining his life as a potential has-been, while the unflappable Booth tries to keep his boss’ spirits up.

It’s worth noting that Tarantino’s loveletter to an America gone (and which existed only for some) also grieves for values currently in decline in 21st century America. In a recent op-ed piece Maureen Dowd observed that “Brad Pitt’s character reflects many values that America once proudly stood for: toughness without belligerence, charm without smarminess, loyalty without question.” And it’s Pitt’s performance that shines most brightly, both in terms of relentless can-do spirit and in terms of living large with a minimum of dishonesty.

It’s worth noting that Tarantino’s loveletter to an America gone (and which existed only for some) also grieves for values currently in decline in 21st century America. In a recent op-ed piece Maureen Dowd observed that “Brad Pitt’s character reflects many values that America once proudly stood for: toughness without belligerence, charm without smarminess, loyalty without question.” And it’s Pitt’s performance that shines most brightly, both in terms of relentless can-do spirit and in terms of living large with a minimum of dishonesty.

You’ll be thinking about that performance, and its implications—and the contrast with the world as it senselessly plays out today—for a long time after the credits finish rolling. (And don’t miss the credits!)

Great details from the get-go. Dalton lives in the big house, a spacious pad with a pool on Cielo Drive up in the hills next to a palatial gated compound rented by Dalton’s idol director Roman Polanski, and his new wife, actress Sharon Valley of the Dolls Tate (Margot Robbie). Already you’re beginning to see where Tarantino might be going with this film, but keep in mind—it’s a fairytale.

After the end of long days on the set—days in which Dalton is getting fewer parts, and Booth is given fewer stunt gigs—Booth drives Dalton back to Cielo Drive in the Caddie, and then hops into his own battered Karmann Ghia for the long commute back to his airstream trailer in Van Nuys.

After the end of long days on the set—days in which Dalton is getting fewer parts, and Booth is given fewer stunt gigs—Booth drives Dalton back to Cielo Drive in the Caddie, and then hops into his own battered Karmann Ghia for the long commute back to his airstream trailer in Van Nuys.

Tarantino gives Pitt a rare chance to stretch. As Booth he radiates easy confidence, part good-humored ex-Vietnam Vet in tight jeans and part highly-trained martial arts expert whose radar is always humming in the background. This is a man who enjoys life, the downs as well as the ups, and his scenes with his beloved pitbull Brandy, are priceless. Pitt is mesmerizing, and not simply because in one scene, a hot day and he’s up on Dalton’s roof checking the TV antenna, he’s forced to strip off his shirt. I’m thinking of writing Tarantino a “thank you” note for that one shot alone. Not since he debuted way back in Thelma and Louise has Pitt looked this good. Capable of serious danger, he keeps his easy grin. Until he doesn’t.

DeCaprio is just as good, and I’ve never been a fan. Rehearsing his scenes in a new Western, DeCaprio’s Dalton is an explosion of hungover rage, humiliation, irritation, and bad luck. When he blows his lines and needs to take a break, he returns to his trailer on the set and proceeds to throw an epic fit of self-loathing, breaking everything in sight and swearing off liquor just long enough to get the scene right when he goes back for another take. And by the way, when he does, he’s spellbinding.

Most of this movie relies upon the rapport between these two actors. Effortless together, they create an easy rider ambience (DeCaprio’s voice is vintage Jack Nicholson), yet their characters have different goals. Booth just wants to get by. Dalton just wants to maintain a public image.

But of course, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, is also about something else that happened in August of 1969.

So we meet Sharan Tate while her husband is out of the country, and she and her former boyfriend (now constant companion) Jay Sebring (Emile Hirsch) go out to all the parties. Tarantino’s portrait of Tate is as a glowing, all-American beauty enchanted by her own good fortune, good looks, and not much else. She flits, and dances, and skips through Westwood Village, even stopping in a theater to catch a screening of her latest film, squealing with excitement at the sight of herself on the screen. The film’s soundtrack, and settings, plunge us into a made-for-Hollywood fantasy of Hollywood itself. Over-the-top eye candy. Just enjoy it. Meanwhile, Tarantino is an adolescent indulging his own fantasies, of Hollywood, of the 60s and of what might have happened one fateful night.

So we meet Sharan Tate while her husband is out of the country, and she and her former boyfriend (now constant companion) Jay Sebring (Emile Hirsch) go out to all the parties. Tarantino’s portrait of Tate is as a glowing, all-American beauty enchanted by her own good fortune, good looks, and not much else. She flits, and dances, and skips through Westwood Village, even stopping in a theater to catch a screening of her latest film, squealing with excitement at the sight of herself on the screen. The film’s soundtrack, and settings, plunge us into a made-for-Hollywood fantasy of Hollywood itself. Over-the-top eye candy. Just enjoy it. Meanwhile, Tarantino is an adolescent indulging his own fantasies, of Hollywood, of the 60s and of what might have happened one fateful night.

The scenes of the Spahn Movie Ranch, owned by an old friend of Booth’s, where the Manson Family has decamped feel chillingly authentic. Nothing short of Sergio Leone-meets-David Lynch is the surrealistic atmosphere of Pitt accidentally meeting the Manson family for the first time. When he returns from checking in on old man Spahn he discovers that his car tire has been flattened, and in “persuading” the bad guy to fix the tire he’s damaged, we first see what stunt man Booth is truly capable of. It’s frankly shocking, all the more so since it’s the warm persona of Brad Pitt’s character that suddenly reveals what’s beneath.

The scenes of the Spahn Movie Ranch, owned by an old friend of Booth’s, where the Manson Family has decamped feel chillingly authentic. Nothing short of Sergio Leone-meets-David Lynch is the surrealistic atmosphere of Pitt accidentally meeting the Manson family for the first time. When he returns from checking in on old man Spahn he discovers that his car tire has been flattened, and in “persuading” the bad guy to fix the tire he’s damaged, we first see what stunt man Booth is truly capable of. It’s frankly shocking, all the more so since it’s the warm persona of Brad Pitt’s character that suddenly reveals what’s beneath.

Pitt, and the character he plays, reveal the secret heart of Tarantino’s film, while the astonishing retrofitting of Hollywood Boulevard by set decorator Barbara Ling plunges us into the archetypal neon, eye-popping façade of Tinsel Town. It is the tension as well as the blurring of that buried rage and superficial sunshine that plays so powerfully in this way-too-long film by Tarantino who, as auteur, can do what he damn well pleases.

The entire film taxes the viewer’s patience as much as it strains even fairytale credulity. But there are scenes to savor that make the experience well worth while (keep in mind Pitt’s abs).

The entire film taxes the viewer’s patience as much as it strains even fairytale credulity. But there are scenes to savor that make the experience well worth while (keep in mind Pitt’s abs).

Back at the Airstream, Cliff Booth opens the first of many cans of beer, then carefully opens two super-sized cans of dog food for his pitbull Brandy. Wonderful timing in Booth’s kitchen ritual as we watch the entire can of glistening brown dog food slurp into Brandy’s chow bowl. Only after Brandy has been told she can eat does Booth sit in front of the TV with his Kraft macaroni and cheese—still in the pan from the stove—and watch an episode of “FBI” on his tiny black and white TV.

And there’s an acting cameo at the Spahn Ranch, which I won’t reveal, also worth the price of admission. And while Robbie is fine as Tate, though not given much more than Breck commercial prancing around to do, it’s the bond between the actor and his double, the boss and the hired hand that makes the film sing. The stunt man actually has lived the life that his buddy, the actor, can only play on the screen

Finally, this is Tarantino, so yes, you can expect to wince during the last half hour of the film. But not for the exact reasons you’re expecting. Pulp Fiction remains the director’s masterpiece, but to watch two fine actors at the top of their game having a great time—as actors and as characters—Once Upon a Time is must-see.

I promised myself I wouldn’t deliver any spoilers, so I have to stop here. There’s tons of semiotic minutiae to dissect. Have fun with it. Especially if you actually remember 1969—this film won’t disappoint.

Before you know it the Kims, who’ll literally do anything to make money, manage to insinuate themselves into the heart of the Park’s splendid household. It is a symbiotic ecosystem made in the hellishly brilliant imagination of this director.

Before you know it the Kims, who’ll literally do anything to make money, manage to insinuate themselves into the heart of the Park’s splendid household. It is a symbiotic ecosystem made in the hellishly brilliant imagination of this director.

The house itself is a key player in what will reveal itself to be Bong’s sly-handed tale of social inequity. An architectural masterpiece (designed by director Bong and made especially for the film) the sleek modernist house is laid out in interlocking levels. The living room’s enormous wall of glass overlooks an oasis of green lawn bordered by a manicured hedge.

The house itself is a key player in what will reveal itself to be Bong’s sly-handed tale of social inequity. An architectural masterpiece (designed by director Bong and made especially for the film) the sleek modernist house is laid out in interlocking levels. The living room’s enormous wall of glass overlooks an oasis of green lawn bordered by a manicured hedge.

And once the shocking visual pyrotechnics have cooled down, the film draws to a haunting, eloquent close a la Charles Dickens. Desperate and ephemeral dreams, of the sort that reveal how much the rich and the poor are mutually bound in a slow dance of need, greed, hypocrisy, and desire.

And once the shocking visual pyrotechnics have cooled down, the film draws to a haunting, eloquent close a la Charles Dickens. Desperate and ephemeral dreams, of the sort that reveal how much the rich and the poor are mutually bound in a slow dance of need, greed, hypocrisy, and desire.

It’s worth noting that Tarantino’s loveletter to an America gone (and which existed only for some) also grieves for values currently in decline in 21st century America. In a recent op-ed piece Maureen Dowd observed that “

It’s worth noting that Tarantino’s loveletter to an America gone (and which existed only for some) also grieves for values currently in decline in 21st century America. In a recent op-ed piece Maureen Dowd observed that “ After the end of long days on the set—days in which Dalton is getting fewer parts, and Booth is given fewer stunt gigs—Booth drives Dalton back to Cielo Drive in the Caddie, and then hops into his own battered Karmann Ghia for the long commute back to his airstream trailer in Van Nuys.

After the end of long days on the set—days in which Dalton is getting fewer parts, and Booth is given fewer stunt gigs—Booth drives Dalton back to Cielo Drive in the Caddie, and then hops into his own battered Karmann Ghia for the long commute back to his airstream trailer in Van Nuys. So we meet Sharan Tate while her husband is out of the country, and she and her former boyfriend (now constant companion) Jay Sebring (Emile Hirsch) go out to all the parties. Tarantino’s portrait of Tate is as a glowing, all-American beauty enchanted by her own good fortune, good looks, and not much else. She flits, and dances, and skips through Westwood Village, even stopping in a theater to catch a screening of her latest film, squealing with excitement at the sight of herself on the screen. The film’s soundtrack, and settings, plunge us into a made-for-Hollywood fantasy of Hollywood itself. Over-the-top eye candy. Just enjoy it. Meanwhile, Tarantino is an adolescent indulging his own fantasies, of Hollywood, of the 60s and of what might have happened one fateful night.

So we meet Sharan Tate while her husband is out of the country, and she and her former boyfriend (now constant companion) Jay Sebring (Emile Hirsch) go out to all the parties. Tarantino’s portrait of Tate is as a glowing, all-American beauty enchanted by her own good fortune, good looks, and not much else. She flits, and dances, and skips through Westwood Village, even stopping in a theater to catch a screening of her latest film, squealing with excitement at the sight of herself on the screen. The film’s soundtrack, and settings, plunge us into a made-for-Hollywood fantasy of Hollywood itself. Over-the-top eye candy. Just enjoy it. Meanwhile, Tarantino is an adolescent indulging his own fantasies, of Hollywood, of the 60s and of what might have happened one fateful night. The scenes of the Spahn Movie Ranch, owned by an old friend of Booth’s, where the Manson Family has decamped feel chillingly authentic. Nothing short of Sergio Leone-meets-David Lynch is the surrealistic atmosphere of Pitt accidentally meeting the Manson family for the first time. When he returns from checking in on old man Spahn he discovers that his car tire has been flattened, and in “persuading” the bad guy to fix the tire he’s damaged, we first see what stunt man Booth is truly capable of. It’s frankly shocking, all the more so since it’s the warm persona of Brad Pitt’s character that suddenly reveals what’s beneath.

The scenes of the Spahn Movie Ranch, owned by an old friend of Booth’s, where the Manson Family has decamped feel chillingly authentic. Nothing short of Sergio Leone-meets-David Lynch is the surrealistic atmosphere of Pitt accidentally meeting the Manson family for the first time. When he returns from checking in on old man Spahn he discovers that his car tire has been flattened, and in “persuading” the bad guy to fix the tire he’s damaged, we first see what stunt man Booth is truly capable of. It’s frankly shocking, all the more so since it’s the warm persona of Brad Pitt’s character that suddenly reveals what’s beneath. The entire film taxes the viewer’s patience as much as it strains even fairytale credulity. But there are scenes to savor that make the experience well worth while (keep in mind Pitt’s abs).

The entire film taxes the viewer’s patience as much as it strains even fairytale credulity. But there are scenes to savor that make the experience well worth while (keep in mind Pitt’s abs).