by Christina Waters | Dec 11, 2018 | Home |

Dear Peter – I know you’re a professional art dealer and connoisseur. You’ve been around the block.

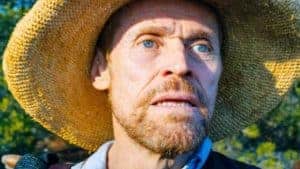

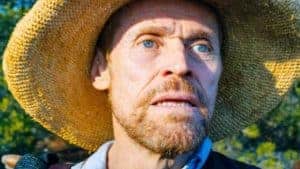

And I also know that, like me, you had a poster of Van Gogh’s Starry Night on your bedroom wall when you were in high school. Who didn’t have a crush on Vincent? We all read his letters to his brother Theo. We were mesmerized by his friendship with Gauguin, their break-up, Vincent’s descent into madness, the thing with the ear. And we weren’t alone.

Turns out that art world poseur and world-class narcissist Julian Schnabel also had a crush on Vincent Van Gogh, arguably the most daring, original, and iconoclastic artist who ever lived. (Van Gogh, not Schnabel.)

Schnabel also has buddies in Manhattan, and he texted them a few years ago and asked if they wanted to come to the south of France. Well nobody doesn’t want to go to the south of France! The result of this fieldtrip is a film, At Eternity’s Gate, so amateurish, so inexcusably uninspired that many an undergraduate would hesitate to submit it as a Film 101 final project.

Full disclosure: sight unseen I already had misgivings about this film. I’d actually sat through Schnabel’s excremental 2007 film effort, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, and so I should have known better. But I’d walk a mile just to watch Willem Dafoe sell vacuum cleaners. So I went to see the latest Schnabel home movie.

Watching the off-kilter, hand-held camera explorations of blades of grass, cobblestoned streets, more blades of grass, and very south-of-france allée of sycamores, it took me a while to realize that these jiggling images were actual directorial choices, not simply outtakes. I could practically hear Schnabel; “okay Will, lay down and close your eyes, grin a lot, and now get up—quick—and run as fast as you can toward the trees! Right, okay. Now lay down in the grass again while I spin the camera around. Let’s get a few close-ups. Great! Now for a beer!”

At Eternity’s Gate produces a sort of existential vertigo. Yes, you know that you’re watching the only actor on the planet who can convincingly play the tortured Dutch artist. But even Willem Dafoe isn’t sure how to inhabit van Gogh. What we see onscreen is Willem Dafoe the actor playing Vincent van Gogh the painter.

He wears the correct French starving artist’s blue shirt, filthy shoes, and dirty suspenders. The straw hat, the easel back pack—all terrifically authentic. And they’re even filming it in Arles! But it ain’t enough.

Dragging the film into cinematic purgatory is Schnabel’s utter cluelessness. Not to mention spoiled rich man’s chutzpah. He doesn’t know what he’s trying to show us about Van Gogh’s last years. He has zero insight, but he does know how to unfocus the camera’s lens so we get that “cool” atmospheric look. (Can it be possible that this is a post-midlife crisis marijuana film? A laid-back retort to the coke films of the 80s? Art therapy?) And all the while we’re forced to listen to what sounds like Schnabel’s grandkids practicing their piano lessons.

And then there’s Paul Gauguin as a Tribeca alt art league organizer, played by Oscar Isaacs, who also has no idea why he’s there except it’s the south of France and what’s not to like?

Schnabel tries to pull his act together once or twice. He allows the artist buddies to actually paint together. And when we watch Dafoe sketching the fields, rocks, trees—looking intensely at the natural world, soaking up the brilliant light and cobalt blue skies—for a moment we feel we are in the presence of van Gogh’s turbulent days at the end of the 19th century.

But the camera starts whirling around again, shifting out of focus (for no particular reason, for no reason that advances the narrative or even provides interesting visuals), and Dafoe is questioned by the doctors, by the priest (an understated Mads Mikkelson), by the asylum director, by the bar maid. Lots of questions. Hmm, thinks Schnabel, that’ll sound deep.

NB: There is no more interesting face on the screen today than Dafoe’s. Perhaps we should thank Schnabel for providing so much of Willem Dafoe to savor. It is impossible not to be mesmerized by his mercurial expressions, the deep grooves of his brow, the wild eyes, the impossible cheekbones, the madness of his teeth. His is a gorgeous facial landscape and this film allows us to devour his least gesture.

Other than the national treasure that is Dafoe’s face, only the scene in which Theo comes to visit Vincent in the asylum lends the film some dignity. Rupert Friend as Theo convinces us of the tender bond between the brothers. As he cradles his despairing brother in his arms, he shows us how desperately alone the great painter must have felt.

But like I said Peter, I came away from this with renewed appreciation for just how super-sized Schnabel’s narcissistic ego must be these days. He got a great actor who looks exactly like Vincent van Gogh to play the part of Vincent van Gogh—and forgot to give him a script, motivation, purpose, inspiration, direction, or insight. (And it took three (3) people to “write” this script, which is pretty much hacked from the letters between the brothers van Gogh.)

At Eternity’s Gate is a waste of time, money, talent, and a once-in-a-lifetime casting opportunity. A craft project by a complete phony, disguised as an art film.

Peter if you truly cherish the work of Vincent van Gogh, you will avoid seeing this film. To see it will pollute your affection for a great painter.

a day in October

by Christina Waters | Oct 8, 2018 | Home |

Carmel without fog, exciting new opera, and a dinner of sophisticated comfort food. What an afternoon! Thanks to the innovative Days and Nights Festival that is one of the West Coast laboratories for friends and colleagues of composer Philip Glass (image: Chad Buchanan), we were on our way to a matinee performance of Glass’ jewelbox chamber opera In the Penal Colony. Story by Kafka, crystalline music by Glass, production by Brian Staufenbiel and chamber orchestra conducted by Nicole Paiement, of Opera Parallele.

On a day warm enough to be called “hot” we parked and walked down into the heart of Carmel by the Sea, oozing visitors, designer canines, and toybox boutiques and found our way to the restored 1929 Golden Bough Playhouse.

The pretty theater on one of those oh so Doris Day residential streets in this landmark town was open for ticket holders to the final day of Glass four-day arts festival. Having worked with the Opera Parallele founders when they were in residence at UC Santa Cruz, we were familiar with the style of performance.

Projected and devised scenic design by David Murakami of what Staufenbiel described to us as “deconstructed animation,” the stage already contained the prisoner of Kafka’s absurdist story. Wrapped in gauze, the figure lay at the center of the Golden Bough’s revolving double stage. Staufenbiel moved his small ensemble effectively within the encircling space, creating non-stop momentum of story and music. The outer circle became the main platform for the table, chair, and ultimately the execution “machine”—a gorgeous assemblage of casket, and shimmering chandelier of lethal spikes, created by Noah Kramer. To the right of the stage, Paiement and her quintet of strings waited to begin what would be a brisk, riveting hour and a half of quintessential Philip Glass orchestration pushing against the gorgeous arias sung by Robert Orth and Javier Abreu, as the Officer and the Visitor.

Like most Glass operas, this one pried open the bloody heart of side-street existentialist themes. Forcing the audience to confront the paradoxes of alleged civilization, surfed on endless variations of Glassian arpeggios.

After the performance Katya and I congratulated Paiement, who introduced us to the composer—a gracious and rumpled 80something—before everyone hit the foyer for wine, cookies, and schmoozing.

On the drive back to Santa Cruz the air grew distinctly smoky. And smokier. A quick call from the car determined two things: a fire in Bonny Doon that was small, and another fire in Solano County that was not small. Smoke from the Solano fire lent ominous beauty to the fields and estuaries near Moss Landing and Corralitos.

Dinner was waiting at La Posta, in midtown Santa Cruz, where chef Katherine Stern showed once again that her conceptual grasp of seasonal flavors keeps stride with the reigning culinary zeitgeist. In New York several weeks ago I had noticed the prevalence of wild herbal flavors and sauces, e.g. sorrel and nasturtium in mains as well as desserts. At La Posta we began with a shared salad of rose-colored chicories, luscious burrata, a few slices of nectarine, a yellow beet, and a dusting of toasted pistachios. Early autumn in every bite.

Katya’s entree was a Fogline Farms chicken breast stuffed with spinach and ricotta, sliced into plump cylinders on a bed of leeks and crispy roast brussels sprouts. My entree was a cittarra spaghetti tossed with housemade Italian sausage, loaded with fennel, Early Girl tomatoes, and spicy red chiles. A dazzling pasta, which is exactly what I expect of La Posta.

Katya’s entree was a Fogline Farms chicken breast stuffed with spinach and ricotta, sliced into plump cylinders on a bed of leeks and crispy roast brussels sprouts. My entree was a cittarra spaghetti tossed with housemade Italian sausage, loaded with fennel, Early Girl tomatoes, and spicy red chiles. A dazzling pasta, which is exactly what I expect of La Posta.

More easy-to-love dazzle came in the form of an apple cornmeal cake,on a pool of fennel crema topped with quince mousse. Unexpected and resonant flavors combined in each bite. Apple, quince, fennel. A brilliant dish.

Then home to watch one of the last episode of The Forsyte Saga. How did we miss it the first time around?

NYC, a few choice meals

by Christina Waters | Oct 3, 2018 | Home |

Living large isn’t really a choice in Manhattan—it’s the law! Especially where food is concerned. From the reliable Pain Quotidien to the Michelin-starred Modern—with bagels, macchiati, gelato, and a few memorable cocktails in between—we sampled with gusto last week in NYC.

Here is a mouth-watering panino—marinated artichoke hearts, fontina and ham—I swilled daintily at the super posh Sant Ambroeus Ristorante at 1000 Madison Avenue. Here the women really do wear Prada and the men all speak Italian. I finished off this inexpensive lunch ($13) with a macchiato and chocolate gelato. That fueled my walk all the way back to Times Square.

Duty-bound, we located the ultimate New York bagel at Ess-a-Bagel on Lexington Avenue. We joined the queue that snaked outside the door for a half hour and finally scored bagels the size of Canaan. Slathered with lox, tomatoes, cream cheese, and onions, these were the motherlode of chewy, dense, delicious. Thank you Matthew for your fieldwork!

The night we flew in, we had a terrific meal at Daniel Boulud’s Bistro Moderne, which I’d booked because it was two blocks from our hotel overlooking the non-stop action of Times Square. Lovely wines, a plump lobster roll with killer french fries for my companion Melo, and fresh wild striped bass on a hash of leeks and peppers for me. Yes, it was a good idea to have a table booked at the end of a day of travel.

The next night was Hamilton, but first a light pre-theater dinner of salmon and pasta at the charming Osteria al Doge (above), another savvy choice a few blocks from the theater.

Our mega-meal happened next—a four course prix fixe at the Modern’s dining room, an elegant but unpretentious tasting tour through one of the better kitchens in Manhattan. Every bite, every sip, lived up to our expectations.

An amuse of fresh tomatos three ways, was joined by the first of several breads and this charming ring of herb-embedded butter (image above). Indulgence in every way (and if you get that pun, you get extra credit).

My first course was a lovely orchestration of seared prawns with toasted pistachios. Next two luscious pieces of lobster with shelling beans in fennel sauce. Duck breast with baby chanterelles (shown here) arrived with the sweet tangy surprise of glazed cherries (all the while I’m enjoying a 2016 Sicilian Nerello Mascalese loaded with the magic of volcanic terroir, but I switched to a pricey-but-worth-it 2015 Domaine Rollin Burgundy toward the end). Dessert, shown here, was as diversely delicious as it looks.

Strawberry bavarian cream, with small ornaments of sorrel cream and nasturtium ice cream. Note the very tiny nasturtium leaf decoration. Oh God. No course was too large, or too small. Every portion was worth eating, and worth having splurged for.

Strawberry bavarian cream, with small ornaments of sorrel cream and nasturtium ice cream. Note the very tiny nasturtium leaf decoration. Oh God. No course was too large, or too small. Every portion was worth eating, and worth having splurged for.

The next night was our other Broadway date, The Band’s Visit, after which we made a pilgrimage to the Algonquin Hotel, and toasted one of our favorite writers with a drink named after her—the Dorothy Parker, a bracing cocktail of gin, lemon, St. Germain served in a cocktail flute. With it we inhaled a wonderful slab of wood-fired flatbread covered with prosciutto and arugula.

I spent the last day in NYC on my own, wandering through the electrifying Catholic Imagination show at the Met, checking out the Louboutin boutique, and ending up having a light supper at the Modern’s Bar Room, an inviting and vigorous place to enjoy brilliant food, fine libations, and meet unusual, avant-garde, and quite frequently entrepreneurial movers and shakers. I’ve eaten here many times—prices are a fraction of those in the more formal Dining Room.

I loved every bite of a basil spaghetti, topped with soft, melting,burrata and toasted pine nuts, paired with a mourvedre/grenache blend.

I love New York, and this visit—with a great traveling companion and the prior decision to cast economic caution to the winds—was the best ever. From the stellar Broadway shows to the gorgeous architecture to the eccentric, beautiful, and well-dressed natives, it lived up to all my expectations. Next time I would skip the overrated Highline (yes, it is nice to see all the new sky-rises at the Docks, but…) and avoid the overly pricey tea at the Plaza (not as wonderful as any in London).

New York is a great city. Don’t leave this planet without a visit.

[more videos and images at my Instagram page]

The Band’s Visit

by Christina Waters | Oct 2, 2018 | Home |

As distinct as night and day are the electrifying Hamilton, and the bittersweet The Band’s Visit. Both deservedly showered with Tony awards, and utterly compelling in utterly different ways.

How could the sweet, short, and succinct tale of a hapless Egyptian band, stuck in the middle of Israeli nowhere for a single night, stand up to the fresh memory of Hamilton? After seeing Lin-Manuel Miranda’s towering hip-hop opera I wondered how anything could survive comparison. Especially given the close proximity of each experience, with only one night’s break in between seeing the two shows.

And I still can’t figure out how it was possible. But it was.

In the magic realist tale turned stage musical by David Yazbek and Itamar Moses, a band of musicians from Alexandria Egypt, outfitted in powder blue uniforms intended to imply dignity, find themselves in a one-horse town called Bet Hatikva (the name itself triggers endless sarcasm and humor). The last bus to where they’re going, a place called Petah Tikvah (yes, it does sound very close to “Bet Hatikva”) has just left. And a small group of bored cafe denizens—including the cafe’s spitfire owner Lina—find themselves reluctantly forced to extend what rough hospitality they can manage. It’s just one night, after all. And the desert casts a spell.

The vignettes that follow, in which we meet a young couple already fighting over lack of money; the town’s unhappy young bachelor; a love-sick young man who stands in front of the single telephone booth waiting for his beloved to call; Dina herself, and her divorced husband; the young couple’s father-in-law and his unquenchable passion for life. Each small story within the village’s dusty little world has its moment in the spotlight. In between, various members of the band create interludes performing mesmerizing Egyptian jazz, klesmer, folk ragas all rolled into one electrifying genre. The music is the soothing and irresistible tie that will bind all these people, Israelis and Egyptians, together for a night that will last for the rest of their lives.

At the center of all these small, vibrant interactions, is the edgy repartée between Dina (Katrina Lenk), with her dreams and cynicism, and the band’s leader, Tawfiq (Tony Shalhoub), a sad man riddled with rich life experience. Over dinner, they talk about the movies and movie stars they loved when they were young, romances lost, dreams destroyed.

Over dinner, they talk about the movies and movie stars they loved when they were young, romances lost, dreams destroyed.

And we dance with them on a jasmine scented wind,

From the west, from the south

Honey in my ears

Spice in my mouth.

Dark and thrilling,

Strange and sweet

Cleopatra and the handsome thief

And they floated in on a jasmine wind

And here’s where The Band’s Visit casts its spell. At first, it seems a rather modest, nicely-played series of scenes, each one crowned by some sweet song. The show is small, intimate, and deceptive. But somewhere in the middle it blossoms into a full dimension of enchantment. Poignant and hilarious—many tears, many tears—the show offers a portal into something as simple, and huge as what it is to be human, to have longings, and to find a reason to press on. Daring to open her much-bruised heart, Dina sings, “Something Different” —the powerful center of the show.

For a few hours, in the middle of a monotoned nowhere, the stories Dina and Tawfiq have shared have created something new. Certainly it is a kind of love at first sight, and yet it’s bigger than that.

And I don’t know what I feel

And I don’t know what I know

All I know is I feel something different

We all know what that is, that elusive yet priceless feeling. Especially when all hope of feeling anything has gone.

The show is short – 1 1/2 hours. Every moment is both ancient and modern. And the music! After the stage goes dark. The lights come up again, and the band sits down—all dozen of them—and plays music like I’ve only heard once in my life: under a full moon on the banks of the Nile.

Hamilton on Broadway

by Christina Waters | Sep 25, 2018 | Home |

I went to New York for business, and what I found was pleasure. Exhibitions, food, people, theater, Central Park, bagels, Saks, espresso—everything won me over. And that includes the antics happening on Times Square far below my hotel window on the 40th floor.

Three main events punctuated our evening schedule: Hamilton, dinner at The Modern, and The Band’s Visit. It had been a half dozen years since I took my mom to see The Lion King on Broadway, so I was more than ready for Hamilton.

No. I was not. I was not ready for Hamilton.

Oh I had been hearing the hype for a couple of years. I remained sceptical. No show could possibly live up to that hype. A show delivered by rap. Give me a break.

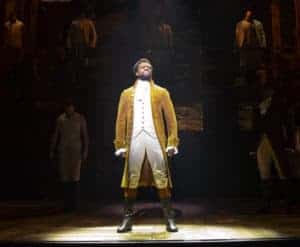

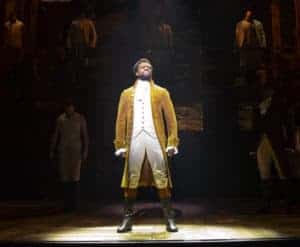

But there I was last week, in the graceful old Richard Rogers theater on 46th Street, in an enviable seat with a close and clear view of the entire stage. And then it began.

The United States was about to be dreamed up by a group of youngbloods in satin jackets, ruffled shirts and buckled shoes.

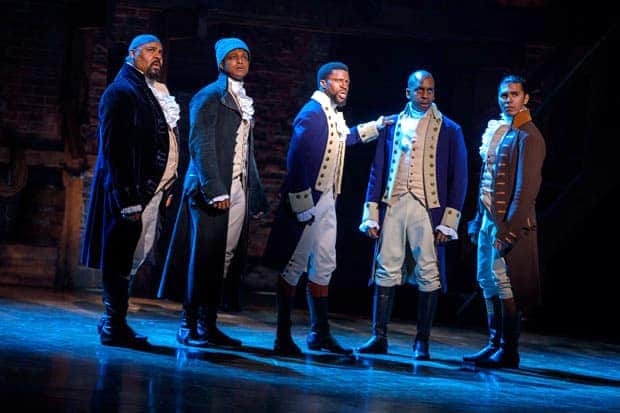

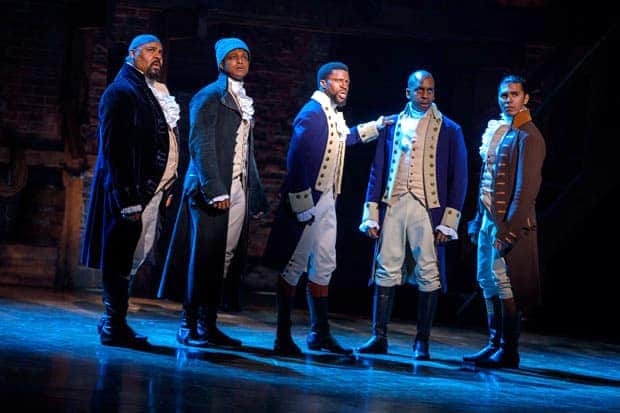

Daniel Breaker as Aaron Burr

Daniel Breaker as Aaron Burr

We, the audience, were collectively spellbound as the latest generation of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s colonial masterminds strutted, pranced, spun, vogued, and devoured the stage. As gorgeous a group of wildly talented men as can be imagined took turns at seducing us, while they plotted ways and means of getting the country up and running.

The revolving stage got a brilliant work-out while each of the founding fathers took turns at making their pitch. The energy alone could have launched a rocket into orbit. And as masterful as is Miranda’s ingenious creation, it thrives on the pyrotechnic energy of its cast, a confident Michael Luwoye as Alexander Hamilton and a scene-stealing Daniel Breaker as Aaron Burr.

Michael Luwoye as Alexander Hamilton

The pumping fury, the life and death struggles of creating a country, struggles laced with personal agendas, suspicions, political lust, and personal indecisions all explode into edgy musical attitude and full hipster movement in Hamilton.

Which, of course you know if you’ve seen it.

And if you haven’t, I invite you to rob a bank, go without wine for a month, whatever it takes to see this show.

I had seen Cumberbatch as Hamlet in London, but I’d never seen anything like this. Surpassing the hype, as well as my expectations, this was what live musical theater was about. Artistic invention that opens broad pathways of discovery. Physical gestures that ignite the story. On Broadway, somehow, I felt closer to the roots, the epicenter of Miranda’s original inspiration. It was the very theater in which Hamilton was born three years ago.

May it always be sold out.

A Timeless “Our Town”

by Christina Waters | Apr 9, 2018 | Art, Home |

American playwright Thornton Wilder won a Pulitzer Prize for his finely-tuned masterpiece, Our Town. First produced in 1938—on a stage completely bare save for some chairs, two tables, and two ladders—it reveals the gritty, glorious, fuzzy reality of what Edmund Husserl called “lived time.” Not the expansive, beginning-middle-end time of fiction or daydreams. But the mundane, emotionally-troubled, worn time of everyday. The lived time that goes by so barely noticed that we, at least those of us over the age of 40, often find ourselves wondering out loud, “where does the time go?”

Thanks to skilled theater professional Suzanne Sturn, the culturati of Santa Cruz have a chance to remember just how true, unflinching, and humbling Our Town remains. Though most of the people in the opening week’s audiences had very likely seen or read the play in their high school years—like good wine, or almost anything by Shakespeare, this play just gets better, and more disturbingly beautiful with time.

Sturn herself plays the loquacious Stage Manager, the person who introduces the audience to the play, the town—Grovers Corners, New Hampshire—and the era, very early 20th century. With pitch perfect and insider wisdom, Sturn’s Stage Manager introduces us to the key residents of the town, the two families who will be joined together upon the marriage of one son George (Maxwell Bjork), and one daughter (Isabel Cruz). With unerring economy—gestures and vocal work do most of the heavy lifting in this production—Sturn moves the residents of Grovers Corners from early morning, to work and school, home again, and then long into the night.

We meet the milkman Howie Newsome (Chris Rich), the town doctor Dr. Gibbs (Dennis Hungridge), Mrs Gibbs (Susan Forrest) who is Emily’s mother, the town newspaper editor Mr. Webb (Bob Colter), and Mrs. Webb (a terrific Gail Borkowski) who is George’s mom. Everything moves smoothly, almost dreamily from the time when the young people are first discovering each other. The middle section of the play, “Love and Marriage,” deepens the awakening of human needs and desires, and introduces a few more delicious players, the town’s hard-drinking choir mistress (played by Mindy Pedlar), and jolly, philosophical Mrs. Soames (Hannah Eckstein).

In their New World Romeo and Juliet roles, courting each other from the tops of ladders, George and Emily unpeel the pain and awkwardness of youth just managing to reach something like agreement about a future together. It is so familiar, so unexpectedly new, so sparingly written, with absolutely not one word too many. Wilder is a humbling precedent for any emerging playwright.

And the final scene, at the town’s cemetery, delivers everything we know is coming. And yet we’re never quite ready for the last scene of Our Town. Sturn’s production utilizes space and time wisely. The players move up and down the aisles of the tiny theater, bringing their hopes, and ours, with them across the thresholds of mortality and whatever might lie beyond.

“Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it?” Emily asks, speaking for everyone who’s ever lived.

If there is anyone who might, against all odds, not know how the play unfolds, I won’t dwell on the final 30 minutes. It’s a surprise worth getting dressed for. But as I watched the play again, struggling for composure, I found myself watching it through my recent reading of George Saunders’ (another Pulitzer Prize winner) Lincoln in the Bardo. Somehow Wilder and Saunders each understood the Buddhist concept of mindfulness, and the need for those of us alive to be released by those we have loved, and lost. The thin, but ultimate membrane that separates life, death, and eternity.

The play itself is better than I could ever have hoped, or remembered. And this production does it justice, making all the right calls in terms of staging and timing. Kudos to the entire cast and director. Thornton Wilder’s Our Town plays at the Center Stage Theater, 1001 Center St., Santa Cruz through April 22. Rife with the magic of an imagined domain that only live theater can realize, this is a production worth two hours and 15 minutes of your time. And then some. Tickets here.

Katya’s entree was a Fogline Farms chicken breast stuffed with spinach and ricotta, sliced into plump cylinders on a bed of leeks and crispy roast brussels sprouts. My entree was a cittarra spaghetti tossed with housemade Italian sausage, loaded with fennel, Early Girl tomatoes, and spicy red chiles. A dazzling pasta, which is exactly what I expect of La Posta.

Katya’s entree was a Fogline Farms chicken breast stuffed with spinach and ricotta, sliced into plump cylinders on a bed of leeks and crispy roast brussels sprouts. My entree was a cittarra spaghetti tossed with housemade Italian sausage, loaded with fennel, Early Girl tomatoes, and spicy red chiles. A dazzling pasta, which is exactly what I expect of La Posta.

Strawberry bavarian cream, with small ornaments of sorrel cream and nasturtium ice cream. Note the very tiny nasturtium leaf decoration. Oh God. No course was too large, or too small. Every portion was worth eating, and worth having splurged for.

Strawberry bavarian cream, with small ornaments of sorrel cream and nasturtium ice cream. Note the very tiny nasturtium leaf decoration. Oh God. No course was too large, or too small. Every portion was worth eating, and worth having splurged for.

Over dinner, they talk about the movies and movie stars they loved when they were young, romances lost, dreams destroyed.

Over dinner, they talk about the movies and movie stars they loved when they were young, romances lost, dreams destroyed.

Daniel Breaker as Aaron Burr

Daniel Breaker as Aaron Burr