Dear Peter – I know you’re a professional art dealer and connoisseur. You’ve been around the block.

And I also know that, like me, you had a poster of Van Gogh’s Starry Night on your bedroom wall when you were in high school. Who didn’t have a crush on Vincent? We all read his letters to his brother Theo. We were mesmerized by his friendship with Gauguin, their break-up, Vincent’s descent into madness, the thing with the ear. And we weren’t alone.

Turns out that art world poseur and world-class narcissist Julian Schnabel also had a crush on Vincent Van Gogh, arguably the most daring, original, and iconoclastic artist who ever lived. (Van Gogh, not Schnabel.)

Schnabel also has buddies in Manhattan, and he texted them a few years ago and asked if they wanted to come to the south of France. Well nobody doesn’t want to go to the south of France! The result of this fieldtrip is a film, At Eternity’s Gate, so amateurish, so inexcusably uninspired that many an undergraduate would hesitate to submit it as a Film 101 final project.

Full disclosure: sight unseen I already had misgivings about this film. I’d actually sat through Schnabel’s excremental 2007 film effort, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, and so I should have known better. But I’d walk a mile just to watch Willem Dafoe sell vacuum cleaners. So I went to see the latest Schnabel home movie.

Watching the off-kilter, hand-held camera explorations of blades of grass, cobblestoned streets, more blades of grass, and very south-of-france allée of sycamores, it took me a while to realize that these jiggling images were actual directorial choices, not simply outtakes. I could practically hear Schnabel; “okay Will, lay down and close your eyes, grin a lot, and now get up—quick—and run as fast as you can toward the trees! Right, okay. Now lay down in the grass again while I spin the camera around. Let’s get a few close-ups. Great! Now for a beer!”

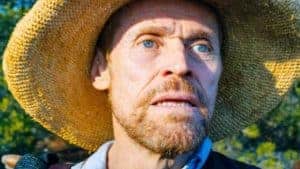

At Eternity’s Gate produces a sort of existential vertigo. Yes, you know that you’re watching the only actor on the planet who can convincingly play the tortured Dutch artist. But even Willem Dafoe isn’t sure how to inhabit van Gogh. What we see onscreen is Willem Dafoe the actor playing Vincent van Gogh the painter.

He wears the correct French starving artist’s blue shirt, filthy shoes, and dirty suspenders. The straw hat, the easel back pack—all terrifically authentic. And they’re even filming it in Arles! But it ain’t enough.

Dragging the film into cinematic purgatory is Schnabel’s utter cluelessness. Not to mention spoiled rich man’s chutzpah. He doesn’t know what he’s trying to show us about Van Gogh’s last years. He has zero insight, but he does know how to unfocus the camera’s lens so we get that “cool” atmospheric look. (Can it be possible that this is a post-midlife crisis marijuana film? A laid-back retort to the coke films of the 80s? Art therapy?) And all the while we’re forced to listen to what sounds like Schnabel’s grandkids practicing their piano lessons.

And then there’s Paul Gauguin as a Tribeca alt art league organizer, played by Oscar Isaacs, who also has no idea why he’s there except it’s the south of France and what’s not to like?

Schnabel tries to pull his act together once or twice. He allows the artist buddies to actually paint together. And when we watch Dafoe sketching the fields, rocks, trees—looking intensely at the natural world, soaking up the brilliant light and cobalt blue skies—for a moment we feel we are in the presence of van Gogh’s turbulent days at the end of the 19th century.

But the camera starts whirling around again, shifting out of focus (for no particular reason, for no reason that advances the narrative or even provides interesting visuals), and Dafoe is questioned by the doctors, by the priest (an understated Mads Mikkelson), by the asylum director, by the bar maid. Lots of questions. Hmm, thinks Schnabel, that’ll sound deep.

NB: There is no more interesting face on the screen today than Dafoe’s. Perhaps we should thank Schnabel for providing so much of Willem Dafoe to savor. It is impossible not to be mesmerized by his mercurial expressions, the deep grooves of his brow, the wild eyes, the impossible cheekbones, the madness of his teeth. His is a gorgeous facial landscape and this film allows us to devour his least gesture.

Other than the national treasure that is Dafoe’s face, only the scene in which Theo comes to visit Vincent in the asylum lends the film some dignity. Rupert Friend as Theo convinces us of the tender bond between the brothers. As he cradles his despairing brother in his arms, he shows us how desperately alone the great painter must have felt.

But like I said Peter, I came away from this with renewed appreciation for just how super-sized Schnabel’s narcissistic ego must be these days. He got a great actor who looks exactly like Vincent van Gogh to play the part of Vincent van Gogh—and forgot to give him a script, motivation, purpose, inspiration, direction, or insight. (And it took three (3) people to “write” this script, which is pretty much hacked from the letters between the brothers van Gogh.)

At Eternity’s Gate is a waste of time, money, talent, and a once-in-a-lifetime casting opportunity. A craft project by a complete phony, disguised as an art film.

Peter if you truly cherish the work of Vincent van Gogh, you will avoid seeing this film. To see it will pollute your affection for a great painter.

C’est si, si dommage… (But I do love your title for this review.)

Christina, thank you for a terrific review of this film! I am not surprised that Schnabel, who in my opinion is a second rate painter but a first rate self-promoter, produced a film about Van Gogh that is really a narcissistic reflection of his own ego rather than a penetrating and sensitive study of his subject’s artistic genius.

I love this movie.

I think Schnabel has a genuine vision.

I only wish Harvey Keitel had been cast to play Gauguin.

Christina, this is a sensational review!!

Can’t wait to see the movie. Do what you

can to get it to come to Maine!