It seemed like a good idea at the time. Composer John Adams and his librettist Peter Sellars immersed themselves in the vivid letters of a New England doctor’s wife who wrote about what she observed in the gold mining camps of the 1850s Sierras. She found colorful men and women, women whose influence was clever and fast and tragic out there in the Wild West. Why not build an opera around the gritty true stories of some plucky women whose fates and fortunes were thus far unknown? The saloon dancers, Mexican camp followers, Asian prostitutes, the girls of the golden west.

Somewhere between inspiration and delivery, alas, the pungent observations of the doctor’s wife, who wrote under the pen name Dame Shirley, went awry. So much material, so few rewards. Mining for a heart of gold, the collaborators of Girls turned up mostly iron pyrite.

Occasionally, peeking out here and there from the thundering cacophany of orchestral syncopation and urgency, there were flashes of the soaring lines and engaging rhapsodies of the John Adams we know from Nixon in China and Doctor Atomic. But such moments were rare and required sitting through the over-long, under-developed arch of what remained just an idea without artistic development.

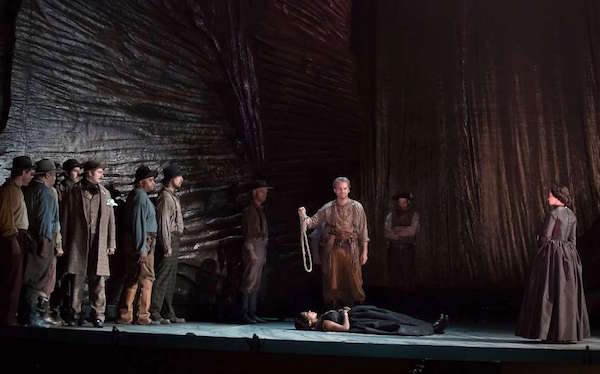

Sellars, who clearly put little energy or invention into the libretto, seemed content to clip out passages from Dame Shirley’s dispatches and have the singers essentially read them to us. Breaking the most elementary rule of theater, Sellars failed to show us the dramas being told. Even with the entire stage of the opera house he found it impossible to show us any dramatic involvement. The opera is devoid of dramatic tension [an exception, shown above, is a ravishing bit of miner’s camp Shakespeare in the form of scenes from Macbeth.] and reveals precious little in the way of actual engagement between characters. Singers came on, they sang words, the orchestra hurled itself through excruciatingly difficult rhythmic passages and then the giant stump that served as the main showcase was pushed a few feet to the left. And then a few feet back to the right.

Sellars, who clearly put little energy or invention into the libretto, seemed content to clip out passages from Dame Shirley’s dispatches and have the singers essentially read them to us. Breaking the most elementary rule of theater, Sellars failed to show us the dramas being told. Even with the entire stage of the opera house he found it impossible to show us any dramatic involvement. The opera is devoid of dramatic tension [an exception, shown above, is a ravishing bit of miner’s camp Shakespeare in the form of scenes from Macbeth.] and reveals precious little in the way of actual engagement between characters. Singers came on, they sang words, the orchestra hurled itself through excruciatingly difficult rhythmic passages and then the giant stump that served as the main showcase was pushed a few feet to the left. And then a few feet back to the right.

Rarely in the annals of opera history has so little been done with so little.

Throughout the set changes, i.e. moving the giant, ugly stump back and forth across the stage, four poor forlorn young women were positioned to either dance, strut, kick, or push a brass bed around in circles. Given no stage direction and only rudimentary choreography, their Greek chorus had all the narrative power of a junior varsity pep rally. Like much of the indecipherable staging, such moments of mining camp hijinks were frankly embarrassing.

Blatantly ugly set “design”—so minimalist as to defy basic Theater 101 strategies—was matched by unappealing costuming, and ludicrous stage direction — again by Sellars, who insisted on the tedious and distracting “open wings” agenda. Somehow the formerly gifted collaborator had forgotten everything he knew about how human beings stand, sit, walk, and become interested in each other.

The Good News

The final performance of this world premiere yielded some gorgeous singing by a vibrant young cast, powered by Adams’ beautiful arias for solo voices, soaring through the inane campfire mayhem and barroom boister.

The final performance of this world premiere yielded some gorgeous singing by a vibrant young cast, powered by Adams’ beautiful arias for solo voices, soaring through the inane campfire mayhem and barroom boister.

As Ned Banks, the freed slave companion of Dame Shirley, Davone Tines [above] was a sorcerer of physical invention and supple bass-baritone vocal power. The stage came to life every time he stepped, danced, and twirled onto it. He transformed Adams’ haunting piece based upon Frederick Douglass’ speech “What to a Slave is the Fourth of July?” into a moment of breathtaking clarity. Tines—destined for stardom—gathered together words and music with as much magic as Adams’ deeply affecting Doctor Atomic aria, “Batter my heart, three-person’d God.”

Why then was he “killed off” two-thirds of the way through the opera? Worse—we are only told that he was killed somewhere off-stage, an event that cried out for dramatization. Another rule broken: you never kill off your most popular character before the end. Once Tines was gone, the opera slowed and meandered.

Another aria, for Josefa, a beautiful Mexican woman destined for the gallows, was sung in Spanish and English by J’Nai Bridges, whose lustrous voice gave elegance and dignity to the superbly surrealist aria Adams created for her.

In other notable performances, Paul Appleby as luckless miner Joe Cannon brought a clarion tenor voice and persuasive acting to his on-stage antics. As another rabble-rousing miner bass Ryan McKinny offered searing moments of vocal beauty and angst. (McKinny already has at least one Wagner role under his belt, and it would be revelatory to hear Tines as Wotan one of these years.) As the raw-boned denizens of the camps, the SF Opera chorus men attacked the repetitive, Glassian declamations with appropriate bravado.

In other notable performances, Paul Appleby as luckless miner Joe Cannon brought a clarion tenor voice and persuasive acting to his on-stage antics. As another rabble-rousing miner bass Ryan McKinny offered searing moments of vocal beauty and angst. (McKinny already has at least one Wagner role under his belt, and it would be revelatory to hear Tines as Wotan one of these years.) As the raw-boned denizens of the camps, the SF Opera chorus men attacked the repetitive, Glassian declamations with appropriate bravado.

The hero of Girls of the Golden West must be the splendid and commanding Julia Bullock, making her San Francisco Opera debut as Dame Shirley (Bullock offered us the witty turnabout of an African-American performer cast as a white woman). Adams gave her some of his finest work in the gossamer opening passages as the she discovers the craziness of California, and at the very end (way too long in the making) in which she proclaims the indelible beauty of the land, transcending its raw, violent male culture.

It’s possible that there is an opera somewhere in all these many ideas—one that brings to robust and emotionally-charged life the rough world of the 19th century mining camps. But Girls of the Golden West is not yet that opera.

Thank you for relief at being unable to attend,rather than the dismay at missing the premier of John Adams’ and Peter Sellars’ latest work.