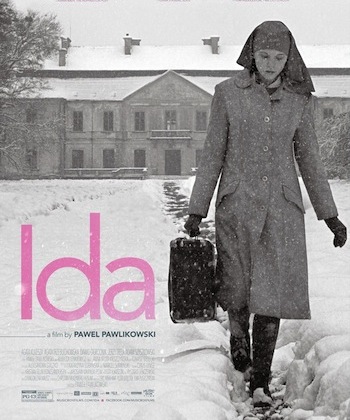

From the first frame, you are hooked. Yes partly because Ida, written and directed by Polish filmmaker Pawel Pawlikowski, is shot in raw black and white. Partly because the camera is most often stationary, allowing actors to move in and out of our viewpoint—creating a softly unsettling sense of time standing still.

But the visual secret of this mesmerizing 85-minute masterpiece is the choice of an almost square aspect ratio. Instead of the wide horizontals of contemporary filmography, we watch the small, unflinching story emerge in a compressed space. The pressure on all sides pushes the action—such as there is in this quiet, steady pursuit of truth lost—pushes it into a space without time. A continuous Now. We could read this film forwards or backwards. Is it redeeming the past? Or is it pointing toward the inevitable recurrence of the future?

The story, if explained to someone who hasn’t seen the film, will sound unlikely. A young novice, Ida (played by Agata Trzebuchowska) about to take her final vows, learns of the existence of an aunt—her only blood relative—and is told she must visit this woman before she can enter the religious life for good.

The aunt is played with the sort of spare visual dominance of a dark Ingrid Thulin by Agata Kulesza, a veteran Polish stage actress who is nothing short of shattering. As a former Communist party judge, the aunt is now devoted to drinking, smoking, and picking up men to kill her own inner pain. What that pain is about forms the very terse, tender and harrowing focus of the film.

The two, an unlikely fairytale duo of innocence and cynicism, the religious and the damned, go on the road to track down the truth about the young novice’s parents. Turns out, we learn almost immediately, that Ida is in fact Jewish, and that the conditions of her parents’ wartime death at the hands of local villagers, are clouded.

Well, all of this—plus the presence of a handsome young musician hitchhiker—makes for a road film that never, ever goes where you think it will. Every action makes existential sense, and unfolds like a single mesmerizing prayer.

The cinematographers Lukasz Zal and Ryszard Lenczewski, place the actors in snowy forests, on muddy roads, amidst the faded ennui of post-war Poland, at low angles. We rarely see their entire figures. The cropping and framing helps to fill the screen with the sense of longing, of emotional confusion, of dumb, blunt, unromanticized quest. We see the two women always through a glass darkly, and the film will remind viewers of Bergman at his best.

I was suspended in a true magical, fictional space watching this real-world attempt to understand a piece of the war, Poland’s complicity with certain actions against the Jews, that no one talks about. No one completely knows. Or wanted to know.

The ending is another surprise that left me breathless. Actually, Ida was one of the rare films that actually ends as well as it plays. Ravishingly beautiful, it allows a newcomer actress to fully express her youthful curiosity and courage, against the harshly-polished edges of a seasoned expert.

Ideally this film would play on a double bill with The White Ribbon.

Very tempting review Christina. Im eager to see this and grateful you brought it to our attention like this!

Sounds good, Christina, I’ll try to catch it at the Nick. Hope it runs more than a week.

Hey, I couldn’t manage to find you at the Mozart tribute at the Civic, while scanning the rows of the chorusters as best I could. With what group are you singing these days?

Bill

I do not believe I could read a more perfect review of this stunning film anywhere.