It wasn’t simply a long week of long, sumptuous operas. It was a pilgrimage. A spiritual journey, in which — thanks to the power of music so beautiful we mortals don’t deserve it — the haunting fact of mortality was made thunderingly clear.

It wasn’t simply a long week of long, sumptuous operas. It was a pilgrimage. A spiritual journey, in which — thanks to the power of music so beautiful we mortals don’t deserve it — the haunting fact of mortality was made thunderingly clear.

The four operas comprising The Ring of the Nibelungen created by Richard Wagner 150 years ago, require stamina, patience, a huge investment of time and money, and the willingness to be open to the magic of theatrical make-believe. For those able to surrender, The Ring rewards with what must be the ultimate performance experience. And every four years since 2001, Seattle has become a world shrine for Wagner’s devoted worshippers.

Valhalla’s leitmotif has been swirling through my head for the past week, blazing with French horns and diminished sevenths. I can only liken it to a biochemical firewalk — once your sensory tastebuds have been consumed in the flames, you’re never the same. And frankly, I still don’t know quite how to articulate the power of the experience. Except of course to say that it offered my jaded eyes the most astonishing production details I’ve ever seen. Singing so magnificent as to alter the course of galaxies … with one exception. Janice Baird’s inadequate Brunnhilde. Her mile-wide vibrato and inaccurate high notes, were matched only by conductor Robert Spano’s often tepid, occasionally incoherent orchestral management.

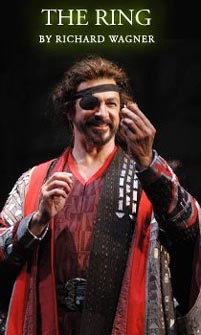

Maybe I’ve been spoiled by the San Francisco Opera‘s outstanding orchestra. But I was unprepared to hear missed notes and hesitant crescendoes during the monumental rolling opening of Das Rheingold. Making up for the inconsistency of the orchestra – and to their credit, these people were literally the hardest-working act in show biz during those long, long performances – were astonishing acting (kudos to director Stephen Wadsworth) and singing on the part of Stephanie Blythe (Fricka; Waltraute) whose instrument is as pure as a Nordic sunset. Outstanding was Richard Paul Fink as Alberich, never better in a role he owns. Greer Grimsley‘s Wotan (in photo above, eyeing the Ring itself) was a powerhouse of mythic machismo, throwing every bit of Nietzschean Wille zur Macht into his pivotal role as the father of not only dozens of demi-gods, but of the last moments of archetypal dominance before the all-too-human reign of mortals begins. Sigh.